The First State-Approved North Korean Novel in English

Esther Kim In Conversation with Friend Translator Immanuel Kim

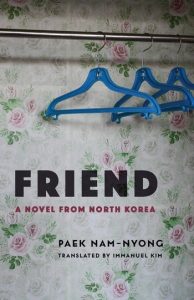

Friend by Paek Namnyong (Columbia University Press, 2020) was first published in 1988 in North Korea where it became a bestseller and a television series that was eventually cancelled. Thirty years later, Friend has become the first state-sanctioned North Korean novel to be published in English, translated by Immanuel Kim. It is, most surprisingly, a novel about love, marriage, and divorce.

Almost all fiction available today from North Korea was written by defectors or dissidents. Paek Namnyong is neither. A household name in North Korea, he worked first in a steel factory for ten years before enrolling at Kim Il Sung University to study literature. Paek Namnyong became part of the elite group of writers known as the April 15th Literary Production Unit. This group is devoted to writing the mythic biographies of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il.

I spoke with Immanuel Kim, a professor of North Korean literature and cinema at George Washington University, about how he found the novel and even flew to North Korea to interview Paek in 2015 before he began translating. Our conversation began with Kim’s journey into North Korean literature. We discussed melodrama, propaganda, and what qualifies as a bestseller in the DPRK. He explained his painstaking search for stories that moved him and what drew him to Paek. In addition to translating Paek Namnyong, Kim is the author of Rewriting Revolution.

*

Esther Kim: What drew you to studying North Korean literature?

Immanuel Kim: When I started my PhD at UC Riverside in 2000, I was reading South Korean literature minus the colonial period [1910-1945]. All of my colleagues were doing the same, and I wondered, What more can I add to this field? What about North Korea? It was a crazy jump. All my friends were like You’re crazy, man. During my first eight months of actually reading the stories, I felt completely discouraged and disheartened. That was until I came across the 1960s novels, which were excellent.

I started making a personal database of authors that moved me. Paek Namnyong was one of them. I read every single one of his short stories and novels. It wasn’t a coincidence. There’s a reason these writers are respected by the Writers Union. Then I started looking for stories that were more relatable to the English-speaking world. I read almost a thousand.

EK: How did you come across Friend?

IK: I first came across Friend while I was doing research in 2009. I went to the North Korean collection at the National Library in Seoul and started reading their number one literary journal. I started from the very beginning and read through the 1960s to the ’90s. They were difficult. All my preconceived notions of North Korean lit were coming true, and I was bored out of my mind. I thought, I can’t say anything significant about North Korean literature! It’s all propaganda and terrible.

The stories were really didactic, but my advisor told me to be patient, and he recommended Friend. As soon as I opened it up, the novel was very different from your usual North Korean literature. Typically, the story focuses on setting, and the action begins halfway through the book. But because of the main character [Sunhee, a celebrity singer], there’s drama from the beginning and I was hooked.

EK: The jacket copy says that Friend is “a bestseller in North Korea.” What makes a bestseller in a command economy?

IK: Unlike capitalist countries, North Korea has a preset number of prints. It’s rare for them to exceed that number and print because of demand. The party produces a list of highly recommended reading, and it’s like their New York Times bestseller list in that it’s used to push readership. These include the hagiographical depictions of the leaders, struggles against the Japanese during the colonial period, history of the Korean War, and anything that edifies the nation. When the party recommends it, I don’t read it.

Was Friend on this bestseller list? Absolutely not. What gives me the audacity to say it’s a bestseller? In North Korea, if a novel is excellent, it’s circulated among the people. If a book is tattered, then you know it’s a bestseller. If it’s pristine, it’s not a bestseller.

“While South Korean melodrama has this love-story formula with lovers parting and lovers getting together, North Korean melodrama revolves around nationalism.”

Paek Namnyong told me a great anecdote. A woman sitting across from him on the bus was reading his novel. He leaned over and said, “I’ll get you a brand-new copy if you give me that one.” He just wanted a souvenir to keep in the office and say, Look, my novel is a bestseller. She looked at him like he’s crazy and got off the bus still giving him a strange look, and then she buried her nose back her in the book.

Whenever I ask defectors, “Have you heard of Friend or Paek Namnyong?” They’re like “Of course!” He’s like their Tom Clancy or Stephen King.

EK: You mention you flew to North Korea in 2015 to meet and interview Paek Namnyong. That interview stretched for three days. Can you talk about that experience?

IK: It was amazing. Since we were only scheduled to meet for one day, I was like I gotta make the best of it. First, I had to gain his trust, so I started spewing all my reading of North Korean lit. I named every author, short story and novel that touched me. He was genuinely impressed.

My minder majored in North Korean literature at Kim Il Sung University. But this fool didn’t know anything about North Korean lit. I was like “Wow, you’ve never read that?” But he’s never read these because it’s not what the party recommended. He had never read Friend. But he knew Paek was a stellar writer because of his reputation in writing about Kim Jong Il.

There’s a difference between what the party wants and what the people want. I stayed away from what the party recommended and searched for what the people enjoyed.

EK: Friend is very melodramatic. It’s got the awkward dating, romance and even mystery. It reminded me of South Korean television dramas, but I recently learned that Koreans were very into melodrama films like Sweet Dreamas early as the 1930s. How does melodrama manifest in North Korean culture?

IK: Koreans love their melodrama. They are overtly and overly sentimental. While South Korean melodrama has this love-story formula with lovers parting and lovers getting together, North Korean melodrama revolves around nationalism. The main characters agonize over the question, “Have I been a good citizen of the state?” Then they’re getting criticized by an elderly comrade and reminded that the most important aspect of life is being devoted to country. But Friend is a bit different. It’s a family novel.

EK: So we can’t talk about North Korean literature without talking about propaganda. Each time I mentioned this novel to family and friends, their immediate reaction was “Is it propaganda?” What are your thoughts?

IK: Well, yes and no. One of the heavy thematic emphases in the novel is family unity. I’m not sure if it’s state-sanctioned ideology. Every government wants the family to be intact for many reasons. I don’t think it’s uniquely North Korean. It’s no different from the family ideology promoted in any other country. Does the state claim and urge its citizens to abide by and live within this family harmony? Yes, but that is not uniquely North Korean.

“In the 1980s, there were a lot of North Korean novels that brought out the strength of women. I won’t say they’re feminist, but they were challenging patriarchy.”

One unique aspect about the novel is that there’s no mention of Kim Il Sung [who was the leader] at the time. Lots of North Korean novels don’t mention the leader. It’s a separate group that fictionalizes the leader. Outside that, if the writers mention Kim Il Sung, it’s a formality, rather than for glorification. Writers who do not mention him are not sent to a concentration camp. I’ve heard an academic claim this, and that’s completely bogus.

EK: There’s a moment in Friend where a teacher contemplates how the children of divorced parents suffer from the separation. I interpreted it as a moment of national allegory with the division of the Korean peninsula. What are your thoughts on this?

IK: Paek’s intent wasn’t to allegorize the two countries. Divorce was so commonplace in North Korea. He was just writing what he saw. The Writers Union office where he worked was on the third floor, and the civil court on the first floor. He’d look out the window and see a line of people, waiting for a divorce. Of course, Paek clarified that he didn’t write the novel because there’s a high rate of divorce in North Korea.

EK: One thing that really surprised me about Friend, and which I found refreshing, was the reversal of gender roles. The father characters are the ones staying at home, taking care of the children and doing the housework while the women pursue a career outside the home. It’s almost more progressive than South Korean society, which is so patriarchal…

IK: Paek’s other novels don’t have pronounced gender roles and dynamics like this one. But something that’s common in all his writing is strong women. His father passed away when he was young, so he lived with a single mother. He grew up with the idea that women are strong, if not stronger than men, and very capable of raising a family with no issues. He has two older sisters who are equally strong, and he’s father to two daughters. So that was a source of inspiration.

In Friend, the women are extremely independent. They question the role of the men. This characterization of women isn’t unique to Paek. In the 1980s, there were a lot of North Korean novels that brought out the strength of women. I won’t say they’re feminist, but they were challenging patriarchy.

In North Korea, they always want the women to work. They say that it’s gender equality but there were more practical reasons. They needed workers. Either in the novel or in real life, from the 1950s to the present-day, the kind of work that women did was and is gender-specific: they’re daycare nurses, teachers, or cooks.

EK: Lastly, what projects are you working on at the moment?

IK: I’m done with literature. My second book project is on North Korean comedy films.

My favorite is Urijip Munjae, or Issues with the Family. I told Paek that’s my favorite movie, and he was like This guy knows what North Koreans like. I showed it to my parents. My dad hates North Korea and considers them the ultimate bad guy, but we watched the film all together and he loved it. It’s got a 1970s humor style. Very dry. It’s not slapstick; it’s not South Korean situational comedy. There’s no laugh track. I find it hilarious.

Whenever I go to these dinners for defectors, they’ll give their dramatic, traumatic story presentation. Everyone’s dabbing their eyes. Then I lean over to the defector and whisper, “Have you heard of such-and-such movie?” Stuff that they must have loved through 1970s and ‘80s in North Korea, and suddenly they forget their tragic story, and their faces light up.

——————————————

Paek Nam-nyong’s novel Friend is available from Columbia University Press.

Esther Kim

Esther Kim is the AAWW's interim Asia Literary Editor for the Transpacific Literary Project. Her writing about books has appeared in The Guardian, Words Without Borders, and The Offing. She is at work on a memoir about her grandfather. She holds a Masters in Korean Literature from the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London) and lives in New York.