A charcoal ring of swallows swung above superannuated walls and landed beside sugared ruins half buried in yellow sands.

A blue waterspout budded out of frothing seas, shattered upon gravity’s fist, and sizzled downwards through the golden prism of a setting sun. Canons detonated above the beaches of Salé, heralding the end of another day of Ramadan.

Arès wandered through unpeopled streets lined by shuttered windows. Moments later, he crested a rise and looked across the river to where the hills of Rabat rolled in sinuous smiles.

For him, Ramadan was a divine dispensation. From sunup till sundown an inviolate truce pacified the streets, and for once the city was his. No stones to dodge; no interpellations; no sibilant hisses trailing his steps; no Moroccans on the beach, muscular from beating blacks. Nothing till the evening, when the sun dipped before the deserted city like the final burndown of a nuclear holocaust.

“If only it could stay like this,” he half prayed to the abandoned streets. He had conceded so much, and his demands had become so hushed. He almost felt as if he could accept this life, if only it would afford him a little peace. He would gladly sell all his dreams for some quiet lanes and a day without worries.

And it was beautiful, he had to admit. The turnabout walls of the ancient medina. The soft, smooth paving stones. The tan fortress burning resplendent at dusk. The singing of the muezzin at the call to prayers. If only the people could be as beautiful as the place, he thought and smiled at his tired joke.

Then the last canon pounded out its breath, heralding day’s end. Around him, the neighborhood spurred into being, and Arès hastened his steps, hoping to etch just one more tranquil lane into his scrapbook of memories. As he strode, he could smell the tantalizing aroma of vast pots of harira, brewing in anticipation of the breaking of the fast, el Fat’r. Inside the quiet homes, spoonfuls of the saffron soup, turgid with cheese and lentil pods, were splashing into ravenous bowls, and small porcelain plates, pyramided with honeyed chebbakia, were delicately being set on tables.

He paused before an open window redolent with the smells of cooking. He was tempted to lean into the window and sniff like a hound. He could just imagine the family’s horrified reaction at his big black face poking in, licking his chops and saying “Hmmmm…”

It would mean another sprinting escape, but the prank was delicious. He stepped a little closer, a lopsided grin on his face. One more step. He was about to grab the windowsill, when he doubled over in pain at a sharp crackling in his stomach.

Despite a reed-thin diet of bread and rice, he had been incontinent for several weeks. He could never be certain, but he suspected that his shower was the cause. The recent battering rains had overwhelmed the neighborhood sewers and plugged the toilets on the ground floor full of wastewater. Since then, an olive-colored stew had gurgled about his ankles while he bathed and worried him awake at night with its stench.

He felt the wave of nausea pass, and he moved on, forgetting his prank.

He couldn’t hazard it in his condition.

But the day was not yet done. He had a destination in mind. Pursing his lips, he began to whistle out a light, chirping tune that the trader had taught him on the road. Then his feet tapped around a corner, and the melody trailed only seconds behind.

*

A week earlier, Arès had come home from a restocking job to find his neighbor’s wife sitting on a puddle of cushions on his living room floor. Beneath the twisted canopy of her hair, she shot him a glance as delirious as it was supercilious. He could see the frilled white hem of her slip and a bulbous nipple sloshing out of her bright yellow tunic.

One of his roommates, a short frantic man from the Ivory Coast named Yaya, was begging her to leave. The woman splayed forward on her knees and began to shout, “Clandestins! Clandestins!” capping the slur each time with a sharp, bugling hiss.

She reminded Arès of the plump canaries caged in the central market in Salé, and he could not banish the image from his mind as he crossed the hall to rap on her husband’s door.

A ferret-faced man poked out his head. He was a tense character, unable to conceal his disrelish at living in a building full of Africans. Arès saw himself reduced, multiplied, and warped in the Moroccan man’s pitch-dark eyes.

“Yes?”

“Salaam aleikhoum.”

“Yes?”

“Sir, your wife is in our living room and she refuses to leave.”

“What? What have you done to my wife?”

“Could you please take her back to your apartment?”

The man shoved his small frame against Arès, and then bungled around him when he did not budge. The young man watched his neighbor fly into his apartment like some wizened vulture and flap his hands against his wife, and finally drive her bawling and disordered across the landing and behind their shut door.

“What happened?” he asked his flatmate. He tried not to grin, but Yaya’s nose twitched comically whenever he was distressed, and it spasmed now like a rabbit caught in a snare.

“I don’t know. I came home and the woman was sitting there. She told me that thieves had broken in and she was looking around to see if anything was missing.”

“The downstairs door was unlocked?”

“No. I used my key to get in.”

“So she is lying.” Arès furrowed his brow, and clouds of worry smoked across his eyes.

“She refused to leave and then you came home.”

“We should check to see if she stole anything.”

They failed to locate a cell phone and a watch. The two men walked back down the landing, one man long, limber, sinews rippling; the other, his nose atwitch, all his weight bundled in a low-hanging chest. They pounded on the door, respectfully at first, then with rising indignation, but it remained shut, silent, unperturbed.

*

Two mornings later, Arès and Yaya carried pans and a batch of loaves back from the communal bakery. When they reentered their flat, she was there. The second they unlatched the door, she flew into a fit of hysterical screeching. The two men stood stupefied while she ripped her dress halfway over her head and thrashed to the floor in a fracas of thumping legs, worming breasts, and paisley-patterned undies.

Confused, they backed out into the hallway. The woman’s shrill cries had roused half the neighborhood, and Arès leaned over the railing as a dozen women in a creamy spectrum of kaftans poured into the building. From above, their glossy hoods and pear-shaped contours called to mind a flock of painted penguins and Arès worked hard to stifle his laughter as they bumbled ungainly up the uneven, buckling stairs.

Then it was no longer funny. Upon seeing the two Africans lurking in the hallway, and hearing the high-pitched squealing from inside, the neighborhood women clawed and pecked the men out of the building.

Back in the street, Arès caught his bearings. Another apartment lost! He threw down the bread in disgust. “Elle nous a foutus!” he exclaimed, infuriated.

“What do you mean?” Yaya asked, confused.

“We have to move now.”

“No. She will leave again in a few hours, or her husband will come home and take her back.”

Yaya put his hand on Arès’ elbow, but he shook it off and squatted in the dust. “It does not matter. She is deranged. She will say we raped her, or attacked her, and we will go to jail.”

“You are exaggerating,” Yaya protested, but his nose twitched worriedly.

“No. You are new here. I have seen this before. The same thing happened in Takadoum, where I used to lived. You must understand. We are guilty. Of whatever she says. No matter how crazy she is. I know someone who is in jail now, if he is still alive. It began just like this.”

“You can move. I am going to stay here with Desiré.”

Arès sucked his teeth. “You can do what you want. You will see. My life since I have arrived has been this. Move, move, move. The Moroccans never leave you in peace.”

“But what can we do?”

“Leave. We must leave. Let me tell you something. Living in Morocco is like living in a port. Nothing is permanent; not work, not housing, not even friendship. And there are only two ways out. On a boat or burial at sea.” He gave Yaya a wild look and stormed off down the street.

He could hardly believe himself, repeating Toti’s words. When he had first heard them, Arès had taken it for the exaggerated cynicism of a tense, bitter man. But Toti had been right.

He wondered for a moment what had become of Toti. Of him and Michaux. He hadn’t run across either of them in months. They had been friends and they had abandoned him. He was hardly even angry about it anymore. The reasons men murdered each other in this place were so minor as to be laughable. At least they had just tossed him out.

He shrugged his shoulders. Either Toti and Michaux were in Europe, or they were dead. There were only two exits from a port.

__________________________________

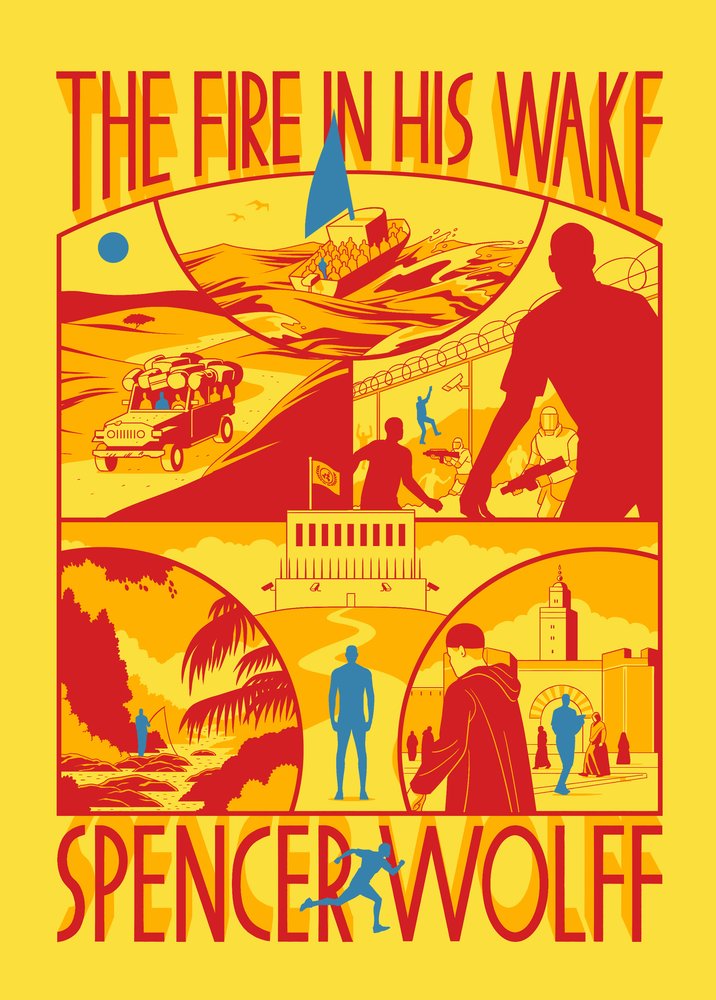

Excerpted from The Fire in His Wake by Spencer Wolff. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, McSweeney’s.