She had enjoyed it more than he had, though the man had wept at the end. They made their way down from the balcony with the rest of the crowd, she walking slightly ahead of him; outside the rain was waiting, a heavy curtain curious as to who would part it and who would baulk. Some braved the torrent, sheltering themselves as best they could, but the couple paused for a moment beneath the stone archway. ‘By providence the heavens kept the rains away until the play was done.’ The man smiled and shook his head. ‘It rained half an hour ago. When the Roman climbed the tree to watch the battle. A drop or two, no more. I saw them splash upon the railing.’ ‘Perhaps it was but your tears you saw?’

The rain was lashing harder as they crossed the bridge and arrived home, their faces and arms wet, their clothes sodden. It was the second day of August, and though their summer clothes afforded little protection, they were easily removed. Both were naked now, the man kneeling before the hearth to light the fire. The woman hugged him from behind, her fingers running over his lips, covering his eyes, tousling his hair as she stared into the first flames that licked the logs, which were slow to catch as though the damp had seeped from the man’s skin. His felt hat lay at his feet, crushed by the weight of the rain that had fallen on it.

‘Why did you weep?’

‘For her. Others wept. You shed no tears, being a woman.’

‘I never weep, however fine the players.’

‘I do not understand why she acted so.’

‘In taking her life?’

‘In suffering. She was beloved by the most eminent men of the age. And the Roman suffered too.’

‘He had to suffer; he betrayed her.’

‘And I cannot understand why ancient tales of love must end in death. Do you remember the youthful lovers of Verona in the sepulchre? No one now dies such a death.’

* * * *

It took them some little time to fall asleep, her more so than him, he drifted off as soon as the firewood ceased its crackling. When first his eyes closed, the woman thought he was pretending and stealthily drew nearer, fluttering her hand between his brow and his lips; he began to breathe quietly. She turned away from him in the bed and lay, still wakeful, until his childlike breath lulled her to sleep.

She was roused by the sun stealing past the shutters they had forgotten to close the night before in their haste to dry themselves and restage the amorous frolics of the Queen and the Triumvir on their narrow mattress, that dance of beaded skirt and heavy doublet in a painted palace. Today was Sunday, and they had no cause to venture abroad, yet his eyes opened when he felt the same ray of sunlight and heard the bells of St Mary-le-Bow toll seven of the clock, then, without returning her kiss, he leapt from the bed, pulled on shirt and breeches and stumbled across the yard to the privy; no sooner had he returned than he was eager to be gone, with not a morsel to eat, with not a kiss for her. What could he be doing on the Sabbath, when he was not called to work at the gaol?

‘A gaol does not close, and there are some fellows would toast my birthday. Will you call upon your sister? I shall be home late.’

* * * *

Night drew in and still the man had not returned; lying awake in bed, Margaret waited. When she heard the first footfalls in the street below, and the voice of a woman chiding a querulous child, she rose and went to her embroidery frame; she had four kerchiefs to furnish for a marriage on Thursday but did not feel disposed to work. When eight bells rang at St Mary-le-Bow, she left the house and walked to Newgate Prison where she sought out Cyril, who, like her husband, had been raised in the West Riding and was the only gaoler she knew by name. Today, they were to execute a priest found guilty of treason and conspiracy against the Crown and a great crowd had massed before the gates. Whole families had come up from the country, the men still garbed in muddy work clothes; noblemen with ready sneezes had reserved seats in the stands, while dogs prowled in search of a master or some gobbet of meat. A cohort of magistrates, stripped of their robes, stood apart from the throng to make it known that they would watch this grisly spectacle only in the service of the law. Margaret became lost among the teeming crowd of women come in search of wayward drunken husbands who had not been seen these two nights since, not even floating in the river, or lawless sons wounded in some tavern brawl on Saturday whom they yet hoped might languish in the cells and not the morgue.

Just then, she spied Cyril at one of the prison gates and strode to meet him; he knew her face and played the gallant for much that she was dishevelled. Thomas had not been seen on Sunday, he said, nor had he appeared this morning at his post, indeed the head watchman was much vexed and had enquired as to his whereabouts. ‘And it is queer he should not come this morning,’ Cyril’s voice dropped to a whisper, ‘when such a notable execution is to be held. We gaolers earn more on certain special days. The common folk and even those sorry wretches behind bars are all dying for a glimpse of the condemned man, and will gladly pay to watch the spectacle. If you wish, you shall have a front row seat over in that corner. From there, you shall see the traitor’s purple tongue loll out as though he died for you alone.’

She made no answer but left the prison, discomfited, taking swift strides as though the legs concealed beneath her voluminous skirts were the only living part of her, the only part able to challenge, to take decisions.

What yet remains within me? You alone remain.

She passed St Stephen’s Church, where as a child she had prayed in terrified silence as she gazed upon the image of the martyr stoned by brutes, their doublets all unbraced; these days, she no longer feared the stones, nor the powerful muscles of the executioners, but St Stephen, as he knelt and prayed, was now but a distant consolation of the hereafter.

Close to hand lived Jane, her older sister, who performed miracles within and without the bodies of women. To those desirous of capturing the attentions of some gentleman, Jane could furnish treacle poultices to firm the breasts, almond milk simmered with spices from India and pastilles of candied flowers to counter the foul breath of age and rotting teeth; the receipts of Mr Morgan, the apothecary who had long served the late queen, were still in great demand at the Cheapside dispensary, though it was Jane who now prepared them in the back room of the shop. From time to time, a flustered manservant would appear at the counter, stammering that his mistress was in need of the ‘other Jane’, the accommodating midwife, the gatherer of simples, she whose occult remedies were fashioned not to beautify but to destroy something that was growing in the lady yet had no rightful name. Margaret had no need of such physic. She walked on through Walbrook, further and further from her empty home and from Jane and her skilled hands. She came to the banks of the river. On the far shore was the circular theatre, the stone archway where they had sheltered from the rain, the words they each had spoken, the verses they had listened to together.

In the afternoon, in the sun’s declining hour, she sat once again at her embroidery frame and there she worked to finish the wedding kerchiefs some prosperous landowners from Twickenham were to give as keepsakes to the most illustrious guests at their wedding. She made the final stitches: crimson silk thread for the berries and, at the base of the burgeoning plant, a tangle of rough, twisted roots, an addition over which she took great pains.

On Thursday, having delivered the embroidered kerchiefs to her patron Mr Gibbons, she made the self-same journey she had made three days before, cast a hateful glance upon the swiftly flowing waters as they swept flinders and flotsam in their wake, but not one corpse, then she headed south across the bridge to the theatre. On Tuesday night, she had seen Thomas appear atop the turret of the theatre in a dream, signalling with a pennant, another woman standing next to him. Now, at the top of the Globe Playhouse, there was only a bare flagstaff: no pennant, no woman, no Thomas. On the esplanade by the stone archway some boys were playing with a ball of rags and string. It was an idle entertainment requiring little effort, with no rivalry, no victors, one that seemed to have no greater goal than to keep the ball sailing into the air, where it tarried a moment before it fell, never to the ground, never swiftly. One of the lads would leap up, catch it, and with a blow from his open palm thrust it towards the heavens. Seeing this beautiful stranger walking in circles and watching them, these angels hurled curses and imprecations, hands cupping the bulges in their breeches that marked them out as men.

On that Thursday, The King’s Men were performing a comedy shown the previous winter at the Globe Playhouse, Volpone; or, the Fox. The play, according to a widow with dyed hair come from Oxford to see it for the second time, was comical, merely comical, with ne’er a hint of tragedy nor a drop of spilt blood. ‘In the play this afternoon, there are none but scoundrels and mountebanks, but tomorrow they play another that I shall also come to see, a courtly tale of wooing in a French forest where all are dressed as others than themselves. This is what I prize above all. This roguish world of the living that I intend to be part of as long as my legs will bear me and there is laughter in my body. Buy a covered seat before there are no more. You shall see we will come out fresh-faced with nary a tear.’ Margaret thanked the woman and went on her way.

How can I go in alone? I have never gone to the theatre alone. Only with you. You were my favourite companion, though you did not know how to dissemble. I do not know either.

Life for Margaret dragged out long and bitter. She left the little house on Ironmongers Lane, it being too large for her needs, and moved into a cramped room two doors from the apothecary where her sister brewed potions and slept upstairs. They spent their evenings together, living like spinsters though both had husbands. Jane’s was in the Navy Royal but, being his sister-in-law, Margaret had seen him only twice, at weddings; her sister’s to the seaman and her own to the gaoler, whom the naval officer had eyed scornfully: a clash of uniforms. ‘I never know where the rascal is,’ Jane mused one night when her heart weighed sadly. ‘Where might he be today? Off the coast of Barbary, perhaps, or sailing closer by to spy on Spaniards.’

Where are you, Thomas Vaughan, now you are not watching o’er your prisoners? Each morning I go to know whether you have returned, well inclined to credit any excuse you choose to give me, but you are never there. The mothers and the daughters of the prisoners now greet me piteously, surmising from my grief that my husband must be a murderer of children or some rabble-rousing papist.

The Welshman who had taken Thomas’s post made clear to Margaret that he was indifferent to her absent husband. He was enthralled by her serenity of gait and speech, her slender hands, to say nothing of what he supposed beneath her skirts. They could live together, and by their thrift spare the cost of two households. Yes or no?

‘No,’ was her sole response. She was not free, nor did she desire the presence of another man.

Someone has left, but he has not left me. Thomas will return.

* * * *

She accepted another job of work from Mr Gibbons, knowing it to be the last. It was an heraldic panel on which she was to broider the arms and likeness of the duke who had commanded it. For many hours and days Margaret laboured upon the design that lay next to her embroidery frame: the sea swell, the furling waves that symbolised the nobleman’s distant voyages, the wild animal and the great fishes he had killed and brought back, anatomised, to England, and in one corner a portrait of his mother embodied as the goddess Juno. But in the central portrait of the duke, Margaret took certain liberties. She fashioned a fantastical body, half man, half beast, which being heroic and as virile struck Mr Gibbons as somewhat bombastic, though exquisitely stitched. ‘Fine work. Ill-judged.’ He paid her for the piece, but dismissed her. And thus she found herself more free and in greater need.

Her sister proposed that she work at the apothecary, offered to teach her how to prepare beautifying unctions, long-lasting perfumes, stimulating tonics, tinctures to relieve pain, and narcotics – the span and compass of the herbalist’s pharmacopoeia. As to expelling the sinful fruits of the womb, Jane alone would tend to such matters. Margaret consented to work there for one week when her sister’s sailor husband arrived home unannounced, his ship having lately docked in Portsmouth, eager to celebrate with his wife his recent preferment to the rank of boatswain. They travelled to the Lakes and, upon their return, the husband bade farewell and rejoined his galleon; Jane, for her part, seemed another woman, one of those same gentlewomen she ministered to with her sure hands. In that week, Margaret had versed herself in the many essences and had devised a receipt for a syrup of liquorice that provoked immediate laughter and, its effect passed, did not lead to prostration. Thus, finding herself contented, she resolved to remain in service at Mr Morgan’s apothecary shop, which welcomed her gladly.

One morning, towards midday, a carriage drawn by two horses in fine livery stopped outside the dispensary and there entered three men and a youth, the latter mewling and kicking. The boy did not wish to have his face powdered nor his cheeks painted with ladies’ cosmetics, but his father, the eldest of the men, commanded. He had paternal authority, the other two had money, and the younger of these, from what Margaret could surmise, was chief among The King’s Men who were presently to stage a new work. On seeing Margaret with the pomade in hand, the boy became calm as though a woman whitening the shadow of his downy beard was no threat to his manhood. He was a handsome lad, though graceless and surly of manner, but a lotion of milk and butter and a curling of his lashes gave him a gentleness that tempered his gaucheness. That very afternoon, he was to play the princess in a tragedy wherein a whole family would perish by reason of a foolish inheritance. In gratitude to Margaret for her patience with the boy, the leader of the company invited her to see the afternoon’s performance. ‘So you may weep free of cost.’ She demurred. She did not care for theatre. Nor for weeping.

She became a young woman who, according to the hours, hated and loved a man. At nightfall, her sister could make her forget her sorrows with waggish tales of what had happened in the day, since often the most notorious ladies among her customers received her in their chambers so that, in secret, she might display the full range of her beautifying potions; one duchess, frustrated by her duke’s faltering desire, and having heard tell from an Italian in Cambridge of a rare device, asked whether Jane could procure a simulacrum of the female genitals fashioned from wax and honey, which, when placed atop the real thing gripped the male member so firmly that its owner never wished to withdraw and would sometimes fall to sleep homo erectus.

Jane had never heard of such a thing, but invented a less extravagant version of the same, just as, to regale her sister, she invented incidents where soldiers returning from battle came to her so she might heal their privates, they having exposed the same – believing it to cure purulent infection – to the scorching sun of Portugal, which left many impotent, and the more pertinacious incontinent. On nights of such drollery, she would sleep often five or six hours at a stretch, only to wake before the day, missing the childlike breath of her husband; not hearing him next to her kindled such heartbreak as might be assuaged by tears dabbed with a handkerchief. Alas she could not weep. Not even at the tragedies of others.

Time did pass, and one afternoon when her sister’s work called her from London, she went again to the theatre. To brood in the theatre. She remembered that soon after their wedding day, Thomas had taken her across the river to see a comedy set in the impossible kingdom of Navarre, and when in the five years of their marriage they had returned to the Globe Playhouse once or twice each summer, how she had delighted to see those plays that unfolded on imagined isles or in lands so ancient they might well be counterfeit. In suffering or in joy, the strangeness of the characters, their fantastical attire, the conjured names of cities yet unheard all seemed to her the stuff of magic, of winter’s tales. So it was that she had allowed him to take her to the grand tragedy that they had seen on the day that Thomas marked thirty years, the day before he left their home never to return. She so despised that day she had forgot the name and the argument of that historic tale set in some far-off land. She remembered two words only: Egyptian puppet.

Where is Egypt?

The sun had emerged after five long weeks slumbering among the clouds that lour until springtime, and the crowds were beginning to gather on the esplanade before the playhouse where, when Margaret first arrived, there were but three beggars and a woman bringing the players’ garments. People came from north and south, by foot and in coaches that waited in the alleys for their masters or left once unburdened of their travellers. Riotous they were, all clamouring together. ‘A joyous rabble,’ she thought. ‘Today they play a tragedy of love,’ she heard a woman’s voice whisper in her ear. ‘A love that truly happened beneath an Orient moon that first blessed then doomed the lovers.’

Turning, she recognised beneath the high falsetto the peevish boy that she had painted, that pale skin she had flushed with red, those eyes that with her own hands she had made a wide and dazzling black with pencil. ‘Are you alone?’ ‘I am never alone. My ladies are with me. At first I did not like it, I played small roles, peasant women or nurses in rude garb. The day you painted me, I played my first young lady; the daughter of a foolish king who bequeaths his lands to her spiteful sisters. Since that day, I have been Juliet and Cressida, the ill-starred Venetian lass strangled by the Moor and bold Rosalind who feigns she is a man. And today . . . ’ ‘Today?’ ‘Today I return since, for the first time in two years, they will play the tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra. Have you no husband to escort you? My name is Nicholas. Nicko, they call me.’

Margaret watched the performance alone, standing near the front of the unroofed yard, as though the story of these wayward lovers, these jealousies, these tricks, these wars fought in bedchamber and on battlefield were new to her. The actor playing Mark Antony was a handsome man who, as he whispered passionately to Cleopatra, gazed at the women in the crowd as though he would seduce them. This did not trouble her, nor did his Scottish accent. Margaret had eyes only for Nicko.

By now, Antony was dead, and Margaret felt it was just that he die by his own hand, by his own sword as the actor reeled and staggered so much among the candles he seemed about to set his tunic ablaze. The climax of the tragedy was yet to come. The grief of Cleopatra. The vanities of sovereigns. The boy actor spoke the words in a still, soft voice, arms by his sides, no waving or gesticulation, no queenly raiment but a plain white tunic like that worn by her maidservant Iras, to whom Nicko announced the humiliation the victors were preparing to visit on her and on her mistress.

Thou, an Egyptian puppet, shalt be shown

In Rome, as well as I. Mechanic slaves

With greasy aprons, rules, and hammers, shall Uplift us to the view.

This was the same Cleopatra who stood upon the stage, her bare feet those of a boy, showing herself to the people of Rome, to the scholars standing behind Margaret who had laughed at the words ‘Egyptian puppet’, to the rude peasant who fell upon the floor in fear when he saw Nicko pluck a writhing serpent from a basket of figs. Standing downstage, the queen allowed her maidservants to bedeck her with jewels, her robe of state, her crown; she seemed to hear Antony call to her. Husband, I come.

She saw how Cleopatra wept for love, and how she died for love, as Nicko pressed the sharp teeth of the viper to his false breast.

The stroke of death is as a lover’s pinch,

Which hurts, and is desired.

Margaret was the last of the much-moved spectators to leave, and she tarried in the playhouse by a stair. There was no one to be seen now. And so she dared ascend the steps, and draw back a curtain which gave onto a chamber with a door; this she opened, to the surprise of three naked boys, the three maidservants in the tragedy, tossing the basket of figs between them as though it were a ball. Nicko was not among them. She asked after him, but the jeering lads said they knew no one by that name. Perchance she sought Cleopatra of the tawny front? She tired of their foolishness and, leaving the chamber, found herself in a darkened hallway with young Nicholas before her.

‘I did not see you weep at my death.’

‘No.’

‘Did I play the scene so badly?’

‘I saw you weep. You played it excellently.’

‘And the words I spoke, did you understand them all? Egyptian puppet?’

‘Perhaps not all. I could listen to your words for hours.’ ‘I have forgotten them already. To me, they are a part of yesterday. Now I must learn those I will speak tomorrow. Look . . . ’

From a trunk he took a painted head with drooping ears.

‘Tomorrow I shall be a queen enamoured of a boor with an ass’s head.’

‘Tomorrow I shall not come.’

‘I shall give you a gift, that you might remember today.’

Nicko unbuttoned the beaded bodice of the queen in which the asp still nestled, with its broidered tongue and eyes of glass, he handed it to her, kissed her twice and, with a bound, vanished into the dressing chamber while Margaret, clutching the serpent, walked back towards the river which, at this hour, raged enough to sweep away the body of a desperate lover. Before she crossed the bridge, she tossed the snake of rags and tatters upon the waters, where it floated, following the current, and disappeared into the darkness.

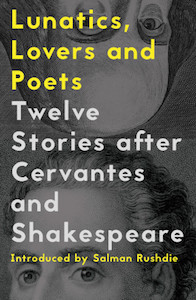

From Lunatics, Lovers and Poets: Twelve Stories after Cervantes and Shakespeare. Used with permission of And Other Stories and Hay Festival. Copyright © 2016 by Vicente Molina Foix; Translation Copyright © 2016 by Frank Wynne.