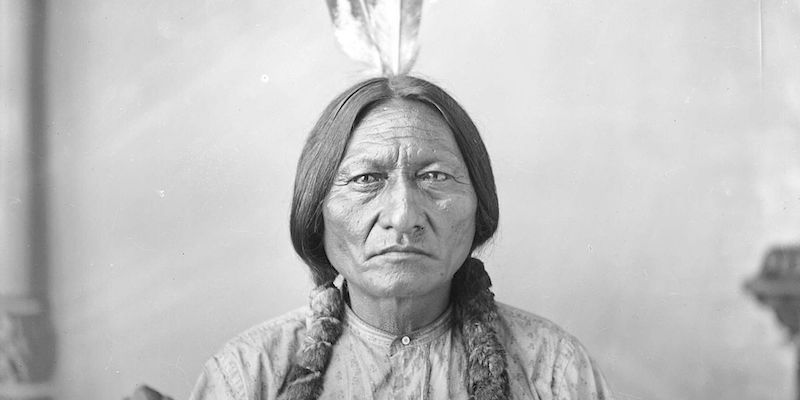

The Early Life of the Renowned Leader of the Lakotas, Sitting Bull

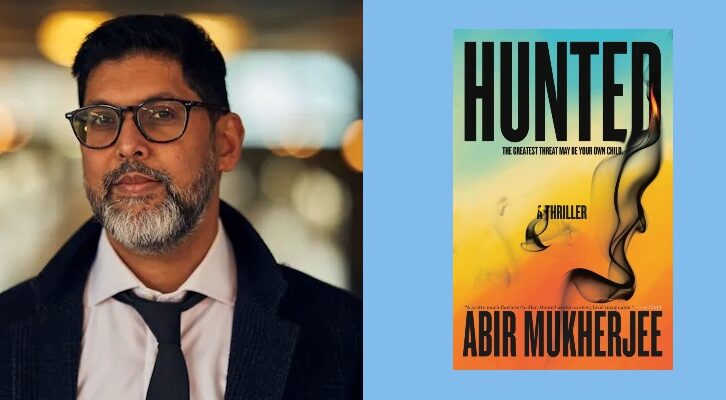

Mark Lee Gardner on Sitting Bull's Transformation into a Young Peacemaker

The baby boy who would one day become the renowned and feared leader of the Lakotas was the second child of Returns Again and Her Holy Door. By all accounts, Returns Again was a brave and wise man, and his name, which could also be translated as “Forsakes His Home,” had everything to do with bravery and warfare. As explained by Sitting Bull’s nephew One Bull, the name referred to a warrior who, after starting home from a war expedition, stopped and turned back in search of more Lakota enemies to battle.

Not only was Returns Again a noted warrior, but he was something of a holy man himself and was known to have powerful dreams or visions. In one dream, a humanlike being appeared in the form of a bird of prey and sang a sacred song to Returns Again. The being gave the Húnkpapa instructions on how to make and decorate a shield, which had to be done at once to receive the power of the great gift. Returns Again made and decorated not one, but four identical shields. The number four was sacred to the Lakotas—many things in the world came in fours: the four directions, the four seasons, and the four ages of human life. Returns Again kept one shield and gave the remaining three away as gifts.

Sitting Bull’s father also had a reputation as someone with a knowledge of nature’s medicines and healing. It was often Returns Again who would treat and bind a battle wound or injury. Despite his many fine qualities and skills, though, Returns Again was not a “big chief ” of the Húnkpapas, a leadership position commonly inherited. He was, however, the ranking headman of his lodge group. A lodge group could number as many as one hundred people, mostly family and extended family that hunted and camped together. Several lodge groups formed a band, and Returns Again’s people belonged to the Bad Bow band. At least nine bands made up the Húnkpapa tribe.

Her Holy Door, Sitting Bull’s mother, was remembered as very social, a good talker who could make people laugh. In addition to her many daily tasks as a Lakota woman, she nurtured her babe so that he would grow straight and strong. Before sleep each night, she took care to cleanse the boy by rubbing buffalo tallow over his body and then tenderly massage his muscles and limbs. As one Lakota explained, manhood was planned in babyhood. The Lakotas’ survival depended upon raising fit men to hunt, protect their people, and maintain their homeland.

“There was no such thing as emptiness in the world,” one Lakota remembered from his childhood. “Even in the sky there were no vacant places. Everywhere there was life.”The name Returns Again chose for his child was Jumping Badger—the adult name “Sitting Bull” would not come for several more years. Why Returns Again decided upon this name is unknown, but bestowing an animal name within a personal name allowed for a connection to that animal’s traits or powers. The badger is an amazingly strong mammal for its size. With its long, sharp foreclaws, it burrows deep into the earth in search of its prey: gophers, prairie dogs, and even rattlesnakes. It is fierce, unrelenting, and fearful of no other creature, certainly very good qualities to possess for any boy aspiring to be a warrior.

But as Jumping Badger grew into a boy, he acquired an unusual nickname. Its English translation is “Slow” or “Slow-Moving.” According to one Lakota account, he got this nickname because he was physically slow (his short legs did not lend themselves to speed), and he spoke slowly as well. In playful contests with other children, he consistently lost. In fact, Slow “was always last in everything.” Other accounts, however, tell us that the nickname came from a certain deliberateness that was remarkable in a child, a tendency to carefully think things out at his own pace. In any event, the boy was rarely if ever called Jumping Badger. Family and friends called him by his nickname, Slow.

As with all Lakota children, Slow’s education and training began soon after he could walk. He would learn to ride horseback, to shoot an arrow so that it flew straight and true, and to catch fish in the rivers and creeks. He would learn the ways of the “winged peoples” and the “four leggeds” and of the earth’s many wonders that flood a child’s mind and senses. “There was no such thing as emptiness in the world,” one Lakota remembered from his childhood. “Even in the sky there were no vacant places. Everywhere there was life, visible and invisible, and every object possessed something that would be good for us to have also—even to the very stones.”

The boy would also learn about the Lakotas’ enemies—such tribes as the Crows, the Assiniboines, the Hidatsas, and the Flatheads. Many were the coups Returns Again counted on Crow warriors. The hatred for the Crows ran so deep, in fact, that even decades later, one old warrior described them as the “most cowardly tribe [that] ever lived on earth.” Why did the Lakotas fight the Crows? Because Crow lands were rich with buffalo, and the Crows had lots of horses.

Of course, the Lakotas’ enemies had nothing good to say about their opponents, either. A Pawnee Indian warned an English adventurer in 1835 that the Lakotas and their allies, the Cheyennes, were “bad men.” In an obvious acknowledgment of the Lakotas’ ferocity, the universal hand sign for the tribe was made by holding the index finger of the right hand near the left shoulder and moving it, in one swift motion, across the throat to the right shoulder, thus mimicking the very unpleasant act of slitting a throat.

*

Naturally, father and mother played an important role in Slow’s upbringing, but so did the village elders, men and women of his parents’ age and his grandparents’ age, regardless of blood relationship. For Slow was not just the son of Returns Again and Her Holy Door, but a son of the lodge group as a whole, which had a vested interest in his development into a good and brave Lakota.

Slow’s most significant mentor, perhaps even more influential than his father, was his uncle Four Horns, the younger brother of Returns Again. Tall and stoutly built, Four Horns was an important chief, the leading headman of the Bad Bow band, and he saw potential in this boy who seemed so methodical and deep-thinking.

Foremost in a Lakota boy’s preparation for adulthood was instilling the importance of the four virtues of Lakota men: bravery, generosity, endurance, and wisdom. Bravery always ranked first. Four Horns and other elders counseled Slow again and again that “You must be brave” and “You must grow into a brave man.” And from an early age, Lakota boys were expected to be like men. When a boy was caught misbehaving, nothing hurt so much as when his mother scolded him by saying a man wouldn’t have done such a thing.

According to One Bull, a common practice to train a boy to have a “brave heart” was to roughly throw him into the cold waters of a river—more than once. The aim was “to teach him patience and to give him a chance to show that he could control his anger,” explained One Bull. “He had to learn to endure this kind of thing and other hardships as well.” One Bull spoke from experience—his father threw him into the river three times.

Another vital aspect of the boy’s training was the horse, without which the nomadic Lakotas couldn’t follow the buffalo, transport their lodges and gear, or seek out their enemies. It started when Slow was so young and small that he had to be tied to his pony’s back to keep from sliding off while learning to ride. When he was older, Slow’s morning chore was retrieving mounts from the camp herd for Four Horns and his father.

With other youths, Slow was enlisted to help train ponies for warfare. One exercise involved having a boy hide in the brush or tall grass near the animal being trained and firing a gun until the pony became used to the blast and would not recoil or flinch. Another was riding and mounting a pony double, the two riders getting on and off the animal multiple times. Thus, in a fight, if a warrior was knocked off his pony—or his pony was killed—he could climb up behind another rider without the pony shying.

Lakota children were also taught to be giving to those with less. “The greatest brave was he who could part with his most cherished belongings,” recalled one Lakota, “and at the same time sing songs of joy and praise.” Four Horns was well known for his kindness to the elderly, and his young nephew was no different. Slow took care to make sure the old and infirm of their camp had plenty to eat, and at his urging, Her Holy Door frequently prepared feasts for them.

Slow demonstrated his willingness to give with those his own age as well. A favorite story told by those who knew him relates how Slow, as a ten-year-old, participated in a contest with other boys to see who could harvest the most beautifully feathered bird. They used blunt arrows to stun or kill the birds without bloodying or otherwise damaging the feathers. When one boy’s best arrow became stuck in the top of a tree, Slow agreed to try to dislodge it with a well-placed shot from his own bow. Several boys watched in awe as Slow’s arrow struck the snagged arrow, sending it plummeting to the ground. But when they ran up to the arrow, it was found to be broken in two. The young owner of the arrow became angry and demanded that Slow replace it.

Instead of arguing with the boy, or becoming upset himself, Slow remained calm. He held out his own arrow, which he considered his best also, saying, “Here, take my blunt point arrow that caused you so much grief. Keep it and get your bird.”

At the end of the day, when it was learned what Slow had done to avoid a fight, he was awarded the prize that was to be presented to the contest’s winner: a bow and arrows made by one of the camp’s best arrow makers.

__________________________________

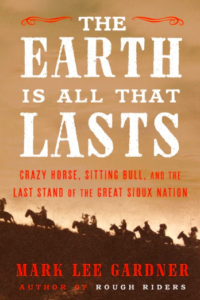

From The Earth Is All that Lasts by Mark Lee Gardner. Copyright © 2022 by Mark Lee Gardner. Reprinted by permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.