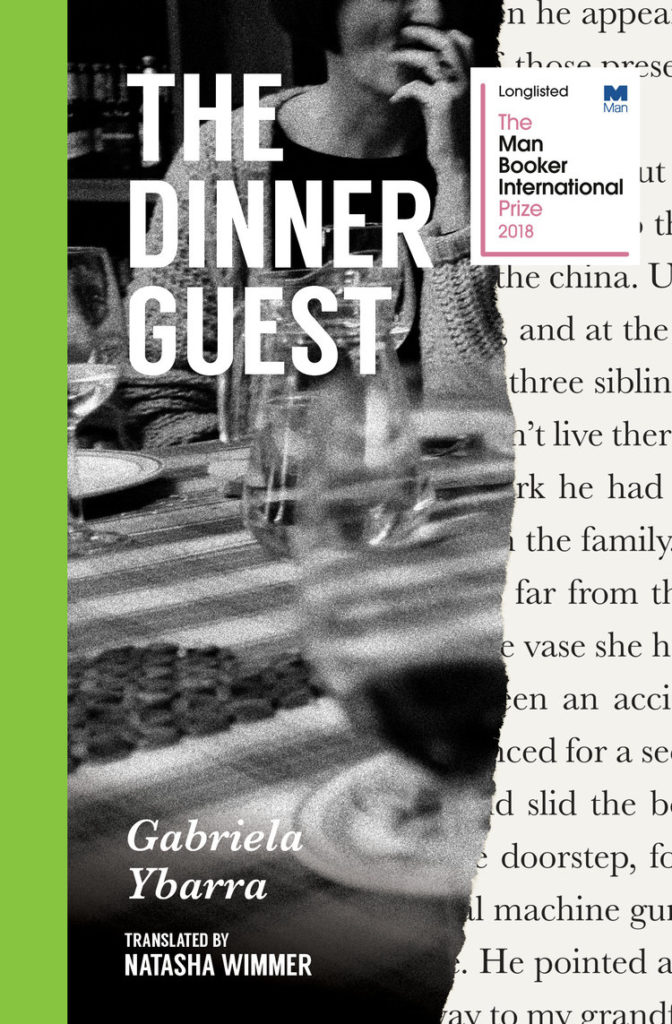

The story goes that in my family there’s an extra dinner guest at every meal. He’s invisible, but always there. He has a plate, glass, knife and fork. Every so often he appears, casts his shadow over the table and erases one of those present.

The first to vanish was my grandfather.

The morning of 20 May, 1977, Marcelina put a kettle on the stove. While she was waiting for it to come to the boil, she took a feather duster and began to dust the china. Upstairs, my grandfather was getting into the shower, and at the end of the hallway, where the doors made a U, the three siblings who still lived at home were in bed. My father didn’t live there anymore, but on his way elsewhere from New York he had decided to come to Neguri to spend a few days with the family.

When the bell rang, Marcelina was far from the door. As she ran the feather duster over a Chinese vase she heard someone calling from the street: “There’s been an accident, open up!” and she ran to the kitchen. She glanced for a second at the kettle, which had begun to whistle, and slid the bolt without looking through the peephole. On the doorstep, four hooded attendants opened their coats to reveal machine guns.

“Where is Don Javier?” asked one. He pointed a gun at the girl, obliging her to show them the way to my grandfather. Two men and a woman went up the stairs. The third man stayed below, watching the front door and rifling through papers.

My father woke when he felt something cold graze his leg. He opened his eyes and saw a man raising the sheet with the barrel of a gun. From across the room, a woman repeated that he should relax, no one was going to hurt him. Then she moved slowly towards the bed, took his wrists and handcuffed them to the headboard. The man and the woman left the room, leaving my father alone, manacled, his torso bare and his face turned upward.

Thirty seconds went by, a minute, maybe longer. After a while, the hooded figures came back into the room. But this time they weren’t alone; with them were two of my father’s brothers and his youngest sister.

My grandfather was still in the shower when he heard someone shouting and banging on the door. He turned off the water, and when the noise didn’t stop, he wrapped himself in a towel and poked his head out the door to see what was going on. A masked man had Marcelina under his arm; with his other hand he held the machine gun pointing through the open door. The man came into the bathroom and sat on the toilet. He grabbed the maid by the skirt and forced her to kneel in a puddle on the floor. Just inches away, my grandfather tried to comb his hair, his eyes on the gun reflected in the mirror. He put on hair cream, but his fingers were shaking and he couldn’t make a straight parting. When he was done he came out of the bathroom and collected a rosary, his glasses, an inhaler and his missal. He knotted his tie, and with the machine gun at his back he walked to the bedroom where his children were.

The four of them were waiting on the bed, watching the woman who had Marcelina by the wrists. In the silence, the whistle of the kettle could be heard.

When she was done securing the maid, the woman went down to the kitchen, set the kettle on the counter and turned off the stove. Meanwhile, on the floor above, her companions shifted the captives.

First they made them move to the ends of the bed, leaving a space. Then they pulled off my grandfather’s tie and sat him in the middle.

The biggest man took a camera out of the black leather bag at his waist and pulled the ski mask out of the way to look through the viewfinder, but neither my father nor his siblings nor my grandfather looked at him. The hooded man snapped his fingers a few times to get their attention, and when he finally succeeded he pressed the shutter three times.

•

A point that has yet to be cleared up is the whereabouts of the photographs that the kidnappers took of the family, and the three snapshots of Ybarra that they removed from the house. “I can confirm that we haven’t received any of the three pictures of my father as evidence,” stated one of the children. “We don’t know what might have happened to them, or to the photographs that were taken of the family with my father moments before he was carried off. The photographs are of those of us who were at home at the time, together with him, saying our goodbyes.”

El País, Friday, 24 June, 1977

•

Mount Serantes was covered by a dense, heavy fog that broke up into heavy rain. Torrents poured down the mountainside into the Nervión estuary, which filled up gradually, like a bathtub. Its banks didn’t overflow, but the banks of the Gobela, a river very near my grandfather’s house, did. On Avenida de los Chopos the water spilled into the street, covered the pavements and surged into garages. Some cars’ headlights came on by themselves. From inside the house the sound of the rain was loud, like someone throwing bread crusts at the windows. Outside, a number of roads were cut off: Bilbao-Santander near Retuerto, Neguri-Bilbao along the valley of Asúa, and Neguri-Algorta.

Beginning at 8.15 in the morning, cars piled up on the roads into Bilbao, in an 18-kilometre traffic jam that reached as far as Getxo. All over Vizcaya, the rain, the cars and the slap of wipers on windscreens could be heard. My grandfather was shut in the trunk of a SEAT 124D sedan making a slow getaway. In the front were two of the kidnappers, with the radio on. No one knew anything yet. “Y te amaré” by Ana y Johnny, could still be heard between traffic and news breaks.

•

The articles from the days that followed the kidnapping are sketchy and brief. The first in-depth report I find was published on 25 May, 1977, in Blanco y Negro, a supplement of the newspaper ABC. It’s titled “The Worst They Can Do Is Shoot Me.” A few lines below, a column heading reads: “Handcuffs French-Made.”

•

When my father trod in the puddles in the garden, he hadn’t yet managed to get the handcuffs off. Upon reaching the gate, he pushed it open with his shoulder and stepped out. Water was rushing over the paving stones. My father scrutinized the street, the lamp post, the bushes, and the soaked hair of a woman loaded with shopping bags who stopped to his left. The woman put the bags on the ground to cover her head and said hello. He answered politely but briefly and walked on, getting wet, until he stopped in front of a house with stone walls, and hedges whipping between the rails of the fence. He rang the bell. He said: “Hello, I live next door. Can I use the phone?” There was a buzz, the door quivered, and a maid with her hair in a bun asked him to come in. She led him into the house, stopped in front of a bone-coloured telephone on the wall and handed him the receiver. When she saw the handcuffs her mouth went a funny shape and she crossed herself. My father, dripping, dialled the police quickly without looking at her. He gave his first name, his last name, his location and a summary of what had happened that morning. Then he was silent, listening to the officer. The maid’s eyes popped, as round as her bun. My father, though, looked calm.

•

Before leaving, the intruders warned my father and his siblings that they couldn’t report the kidnapping until midday. At a quarter to twelve, two of the brothers managed to pull free of the bed frame. At twelve thirty the police arrived, followed fifteen minutes later by the press.

The officers freed the women first. Last was my youngest uncle, who, once he was released, ran down to the garden to shout my grandfather’s name among the hydrangeas. My father spoke to the reporters on the porch. They stuck their tape recorders under his chin and he said, “Everyone behaved impeccably. We were calm throughout it all.”

As the lunch hour neared, more policemen and reporters came. The rest of the siblings and some cousins arrived too. The oldest brother gazed down the road. Meanwhile, the youngest was still in the garden looking for my grandfather in the hydrangeas.

•

The oldest had blue eyes and was wearing a green anorak and jeans. The second, dark and thin, was wearing a dark checked shirt. The woman, slim, was wearing an orange raincoat. The fourth, of medium height, never took off his white coat. The four assailants ranged in age from twenty to twenty-five.

Blanco y Negro, Wednesday, May 25, 1977

–Translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer

__________________________________

From The Dinner Guest by Gabriela Ybarra. Used with permission of Transit Books. Translation copyright © 2019 by Natasha Wimmer.