The Deliverance of Douglas A. Martin's Obsessive Desire

Hugh Ryan on Outline of My Lover

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a queer handful of books took on a central place among my friends, as well as the people I was not friends with yet but might someday be. We stuffed the back pockets of our oversized JNCO jeans with beat up paperbacks, flagging Michelle Tea top or Baudelaire bottom. We treated them somewhere between sacred text, samizdat, and shibboleth. They were the path and the sign you were on it. We were all two-shoes-too-goody to live life like our semi-fictional anti-heroes, but back then, just being a dyke or a fag was enough to make us feel like dissipated outsiders, even as we followed (most of) the rules.

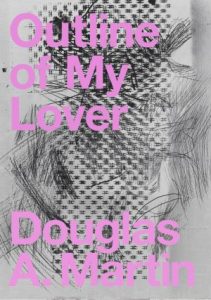

Outline of My Lover was the last of those books, and the most affecting. A slim white paperback with sensually curved corners, it defied convention and category—was it nonfiction published as fiction that read like poetry? Or fiction that drew on nonfiction for its content and poetry for its form? It was genre-queer before we knew the term, and the undeniable physical fact of its uncategorizable existence was (to us) permission in material form: write well, and you could write anything.

Plus, it came with a lore: it was published by Soft Skull Press, an indie house in New York City whose first books were secreted together in the back of an all-night Kinko’s copy shop. It was what our college ‘zines dreamed of being in their next lives.

But it was the prose that really caught me—the broken rhythms and strange juxtapositions that gave Outline of My Lover its fierce intentionality. Every word felt not so much written as pinpointed on the page, measured as much as a unit of sound and space as a conveyor of information. Sentences adhered oddly, their stuttering syllables and profligate commas herky-jerky and extraordinary. Because I could not predict their wend, the lines demanded my fullest attention.

My inability to sleep in a strange bed with the boy across from me wakes me in the middle of the night. Down two flights of floors, our room on the second. Out the heavy metal door I go into roaming over the different dark of campus.

I walk waiting. Something is going to, something is going to happen to me.

Douglas’s sentences made me breathe in his narrator’s time. Two people synced through something intangible—isn’t that the essence of storytelling?

Outline of My Lover was a treatise on limerence, obsessive desire for something you can’t have, at least not the way you want. Even in achieving a relationship with his guide star, the unnamed narrator knows nothing will last. His was a rarely articulated position: the cunning pathétique, whose acts of submission are as calculated as they are genuine. He gets what he wants by becoming what is wanted.

I am dying for him, in a sense, abandoning childhood and entering it at the same time, a new one, everything over to him and his hands to learn over, start under, again with my idea of who I am.

As queer twenty-nothings, this was a deliverance my friends and I longed for. We played regularly at reinvention, constantly finding new selves we thought might be ours. After Outline of My Lover, we read The Haiku Year—a book of poems collectively co-authored by Douglas and friends—and embarked on our own ambitious plan for a year of daily shared poems. Do I even have to tell you, we lasted a week?

I’d internalized something from Outline of My Lover, less a lesson than a sensibility, or maybe a hunger.

Surprising ourselves only, we grew up (or at least older) and lost touch. Outline of My Lover, however, stayed constant. It was time condensed down into space, a piece of my history I could lend out—until the day it didn’t come back. Occasionally, thereafter, I reached for it, like a tongue worrying the spot a tooth had once occupied, but it was gone, as completely and suddenly as my twenties themselves.

Or so I thought until I started writing. Seriously writing, not that piddly shit I’d been talking about doing for years. I’d find myself contemplating a banal sentence and wondering how I could break it to feel new again. I’d find myself contemplating the truth and wondering the same thing. In graduate school, I studied “nonfiction” that erased the line between genres, a skinny family tree’s worth of books whose roots—or me—always reached back to that white paperback with curved corners. I’d internalized something from Outline of My Lover, less a lesson than a sensibility, or maybe a hunger. From a permission it had become a goad: write well, or why write anything?

When Douglas invited me to be part of the this anniversary edition, it felt like coming full spiral—returning to something I knew well, but on a new level. Again and again, his book has kissed up against my life and retreated, offering something new each time. Already, I look forward to our next encounter.

__________________________________

From Outline of My Lover by Douglas A. Martin, with a foreword by Hugh Ryan. Used with the permission of Nightboat Books.

Hugh Ryan

Hugh Ryan is a writer and curator, and most recently, the author of The Women's House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison, which won the Israel Fishman Stonewall Book Award from American Library Association. His first book, When Brooklyn Was Queer, won a 2020 New York City Book Award, was a New York Times Editors' Choice in 2019, and was a finalist for the Randy Shilts and Lambda Literary Awards. He was honored with the 2020 Allan Berube Prize from the American Historical Association.