The Decade John Berger Became an Art World Revolutionary

Joshua Sperling on His Turn to Reinterpreting the Past

What makes a revolution? And what follows in its wake once one has been made? These are questions that may strike the contemporary Western reader as nostalgic. They are redolent of a past age, before history was said to have ended, and entered overtime. We continue to speak of revolutions in business, in style and technology; but rarely in politics does it mean what it used to mean. Or, for that matter, in art. It has become easier for us to imagine a disaster so vast as to make the planet uninhabitable than to see far beyond the capitalist world order that everywhere surrounds us. Only after some great cataclysm will we be able to press the reset button and start afresh. This is the latent utopian content of so many summer blockbusters.

But to go only two generations back is to inhabit a different world with a different conception of the future, a different sense of the possible. The crucial dates for the European left—1789, 1848, 1871, 1917, 1968—attest to a radical lineage in which revolution occupied a central and recurring position in its psyche. History was shown again and again to be a living, writhing force. Popular energies would erupt, lose control, be put down, re-emerge, and be put down again only to reappear, often spectacularly. This was the stop-and-start of the long 19th century. And in those revolutionary moments—windows of mass disruption and seemingly irrevocable historical change—the political vanguard can be said to have been living the dream, convinced in the moment that a second coming was near at hand.

For John Berger, who began not as a dreamer of the maelstrom but a campaigner for tradition, the very concept of the total transformation, sudden and exhilarating, was something he came to only later, after his hopes for postwar unity had dissolved. His early taste of political disappointment was in this sense unusual. It was not that the revolution of his youth had gone wrong or failed to come, but that the revolutions that did come, whether cultural (from America) or political (in the Eastern bloc), were of the wrong kind, from the wrong quarters. Meanwhile, the artistic New Deal he tried to encourage, as if brick-by-brick, was buckling under the weight of its own ambition. Like a rising tide, middle-class prosperity brought with it a host of new attitudes and aspirations: so-called “ad-mass” culture, “never had it so good” Macmillanism, the Americanized cult of cool.

The year 1956 saw, in the United Kingdom, the birth of Pop Art as a practice, cultural studies as a method, and the “Angry Young Men” as a generational signifier. By the following year two myths had given way: the myth of the Soviet Union and the myth of “the people.” In January a donnish Kingsley Amis could complain of a whole generation of young men “shopping” for causes to believe in—only to find the larder empty; while in a more can-do mood Anthony Crossland urged the Labour Party to shed its dreary populism and get in step with a jumpin’-and-jivin’ new England. It was only three years before the Beatles started playing clubs in Liverpool.

Having staked his sense of self to larger historical forces more imagined than real, Berger had to confront defeat. “In the end we must await new men for a new integration of the arts,” he said in 1956, “and in the meanwhile we can only struggle to improve the separate component parts.” With the perspective of a few years, he could analyze his failure. He had misunderstood, as he put it, “the contemporary, social role of the visual arts in Western Europe,” mistakenly believing that painting and sculpture “could develop in as broad a way as the other arts.”

As new technologies (radio, cinema, television) usurped the role of popular communication, the visual artist was left entirely dependent on the bourgeoisie. “Consequently,” he said, “we socialist realist critics were wrong to demand or expect artists to produce direct, urgent social comment. This was to imprison them in the most frustrating contradiction. They became disillusioned either with their medium or with their content.”

But what remains of our hopes, Berger also said, is a long despair that will engender them again. Sometimes it is not so long.

No longer championing the coming art of the future, he now championed what was lost but revolutionary in the art of the past.

Out of the crisis of 1956 came a period of self-examination and renewal that went by the name of the New Left, and then, following on its heels, the cultural big bang more widely known as “the sixties.” The explosive rearrangement, first within English Marxism and then as part of a globalized mood of rebellion, meant that Berger was free to reinvent himself. A new marriage to the Russian-born translator Anna Bostock and his more or less concurrent departure from England signalld a rebirth: this was the beginning of his prolific, peripatetic middle period. As he wrote in a 1962 poem published in Labour Monthly, less than a year into exile:

Men go backwards or forwards

There are two directions

But not two sides.

For Berger, forwards meant the continent, and it meant a new kind of writing. It meant living out as an artist the possible syntheses he had only glimpsed as a critic.

Though based in a suburb of Geneva, he spent much of the decade on the road. And as the generation of ’68 spread its wings his work similarly broke free of all established models. He produced an awe-inspiring array of forms: photo-texts, broadcasts, novels, documentaries, feature films, essays. It was a sensual yet heady decade and a half. Riding from museum to museum on his motorbike, staying with friends in country homes, painting landscapes in open fields, making pilgrimages to altarpieces and monuments, seeking out the buried manuscripts of the interwar left, speaking at marches and teach-ins: all this went into his new identity as a European—rather than English—writer. If Berger first made his name in the polemical blood sport of London, the figure that emerged as the New Left rose to a crescendo was a theorist in transit, a critic writing back to his homeland. A total transformation indeed.

The late 50s were an exit ramp. After his leave from journalism, his time spent away from London, the publication of his first novel, the dissolution of his second marriage, the collapse of his social realist project—after all this, Berger returned to the New Statesman for three final years. From 1958 to 1960 he once again contributed articles on exhibitions, but his focus had changed profoundly. Any interest in contemporary art shrank to the point of dismissal or indifference. A review of the 1958 Venice Biennale was titled, succinctly, “The Banale.” The only serious attention he gave to a postwar painter, other than to a couple of friends, was to Jackson Pollock. But even here there was a new outlook.

Pollock had recently died in a car crash, and Berger no longer protested against the “hard sell” of New York modernism. In an essay still widely read, he argued instead that Pollock’s immense talent (which he had come to admit) could only reveal itself negatively—in vivid testaments to its own waste, graffiti on the prison walls of a jettisoned mind. “Having the ability to speak,” Berger wrote, “he acted dumb.”

Berger let go of his identity as a crusader (the Holy War was over) to refashion himself as an art-historical searcher.

Pollock’s failure, he concluded, stemmed from an inability to “think beyond or question” the cultural situation to which he belonged. As if heeding his own cautions, Berger’s writing grew in historicity and scope. Of course there had always been, interspersed with the polemics, studies of masters: Courbet, Goya, Kokoschka, Chagall. But he now studied the art of the past with a more synoptic lens. He asked larger questions. What can painting tell us about the development of human consciousness? How might our senses be colored by civilizational belief? What place do artists occupy alongside thinkers from other fields?

He wrote of Velazquez in relation to Galileo, Poussin in relation to Descartes, and Picasso in relation to Heisenberg. When he appeared on Huw Wheldon’s Monitor, he spoke of four Bellinis separated by the revolutions of Copernicus and Vasco de Gama. The parallels were of course more evocative than rigorous—he was aware of the pitfalls that came from treating art as merely an adjunct to the history of ideas (a criticism often leveled at the iconographic school of Erwin Panofsky); but he held firm to the fundamental premise. “One must remember that neither scientific nor artistic developments are independent,” he reminded his readers. “The questions that scientists and artists put to themselves have been created by the same history.” (It was an insight, itself historical, that seemed to be self-consciously borne out, as thinkers as dissimilar as Thomas Kuhn and Michel Foucault concurrently arrived at their own versions of constructivism.) All fields both condition and are conditioned by the ideological possibilities of their time. Or, as Heinrich Wölfflin, the godfather of modern art history, put it some fifty years earlier: “People have at all times seen what they want to see.” “Vision itself has a history,” he proclaimed. And the “revelation of these visual strata” was the primary task of the scholar.

The two primal scenes for Berger (not a professional scholar but a critic and writer) were the Renaissance and modernism. As philosophical revolutions, each stood comparison with the other, but the second, more recent lineage deserved special attention. And with good reason: for years it had been off-limits, the visual equivalent of samizdat. But as the fog of the Cold War lifted Berger could see further afield. Soon he was transfixed.

The pictures that so engrossed him were by painters now familiar to all of us: Manet, Monet, Degas, Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso. Much of it made in Montparnasse, the canon of French modernism become his own Mount Parnassus: a massif to be visited and to lose oneself in. “It was like being roped together on a mountain,” Braque said of his time with Picasso—a metaphor Berger loved.

At the summit was cubism. Berger viewed the paintings Picasso, Braque and others made on the eve of World War I to be a seminal break in Western Art. In itself the idea was nothing new—all art historians view cubism as a threshold; but what he said of the movement deviated wildly from art-historical convention, in both shape and method. Cubism was not extended by abstraction, Berger said, but betrayed by it. Even as its stylistic legacy was ubiquitous, discernible in everything from office buildings to coasters, the revolutionary promise of the work remained frozen in historical amber. Could there be a prelapsarian modernism? A modernism before the fall? As he pursued such questions, Berger let go of his identity as a crusader (the Holy War was over) to refashion himself as an art-historical searcher: a reconnaissance pilot flying above a lost geography of promise. And yet the missionary zeal of his early campaigns never entirely left him—it simply changed forms. No longer championing the coming art of the future, he now championed what was lost but revolutionary in the art of the past.

__________________________________

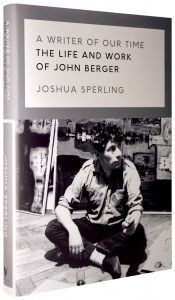

From A Writer of Our Time: The Life and Work of John Berger by Joshua Sperling. Used with permission of the publisher, Verso Books. Copyright © 2020 by Joshua Sperling.

Joshua Sperling

Joshua Sperling was born in New York City and grew up in California. His writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, Guernica, Film Quarterly, Jump Cut and Bullett Magazine, among other publications. He received a PhD in Comparative Literature, Film and Media from Yale University and currently teaches at Oberlin College.