The Compelling Tales We Tell of Fictional Tigers

Katy Yocom on Ten Enduring Stories of an Endangered Species

At first I was merely charmed. A tigress at the Louisville Zoo gave birth to a litter of cubs, and I visited weekly, watching them grow from tottering fuzzballs into leaping, pouncing youngsters. The best visits yielded stories: the day little Leela tumbled into a stream and discovered to her astonishment that she could swim. The day Jai and Mohan paraded around single file, one holding the other’s tail between his teeth, looking like characters from Dr. Seuss’s “King Looie Katz.”

I began reading books by naturalists, and they taught me that every encounter with a wild tiger has its own narrative arc. Even if a tiger is resting in the shade, doing nothing in particular, there’s a story there. You see it in the tales of hunting expeditions recounted in the 1944 classic Man-Eaters of Kumaon by Jim Corbett. You see it in Spell of the Tiger by Sy Montgomery, in which the only defense against tiger attack is the intercession of gods.

Those books also confronted me with a truth I already knew, if vaguely: that the fate of tigers hangs in the balance. I still visited the zoo babies, but now I saw their bright faces in the context of an impending disaster.

It’s a fraught thing to get mixed up with an endangered species. My novel, Three Ways to Disappear, grew out of that clash of love and grief. I imagined a character, an American woman who moves to India to work for tiger conservation, driven by the aftereffects of a long-ago family tragedy.

I began to hunt for tiger encounters of my own.

That quest took me halfway around the world, to Ranthambore National Park in the Indian state of Rajasthan, a landscape teeming with wildlife—not only tigers but leopards, langur monkeys, chital deer, wild boar. One cool, sunny morning, I saw a subadult tiger capture an infant deer and lie down with it, uncertain what to do. Finally it picked up the fawn by the back of the neck and carried it into the tall grass.

My memories of these encounters remain indelible. The zoologist Ullas Karanth said, “When you see a tiger, it is always like a dream.” Yes—but a vivid one. Because it could so easily kill us, our senses go on high alert in the presence of a wild tiger. We cannot look away.

Yet we are so close to wiping them out. People are often surprised to learn that fewer than 4,000 wild tigers live in the world today. Their numbers have plummeted since the beginning of the twentieth century, due first to hunting and now to poaching, habitat loss, climate change, and the trade in their body parts for use as medicine—an ironic side effect of their immense charisma and power. It’s not a coincidence that the Sanskrit word for tiger is viagra. And while there are no actual tiger parts in pharmaceutical Viagra, there’s considerable demand in some corners of the world for tiger penis soup to bolster male sexual performance. Tiger bones, brains, whiskers, and claws are also in high demand as remedies for other ailments.

More than one early reader has used the word “longing” in reference to my novel. What they are describing is the tension between my love for tigers and my fear for their fate.

Here are the ten best tigers in fiction.

Yann Martel, Life of Pi

My first tiger as an adult was Richard Parker, and I loved him passionately. True, he wanted to eat Pi, but every time Pi tended to him and Richard Parker allowed it, my heart lifted. The privilege of that contact moved me: the human serving the wild beast. Take that literally or metaphorically—and the novel invites you to decide for yourself—the relationship between Richard Parker and Pi is a master class on storytelling, faith, and the terrible will to live.

R. K. Narayan, A Tiger for Malgudi

An aging Bengal tiger looks back on his eventful life. When he meets a guru, he learns to adopt the way of nonviolence. This slim novel, told from the tiger’s point of view, gives us a life spent evolving, finding companionship, and finally letting go. In the introduction, Narayan writes, “[W]ith a few exceptions here and there, humans have monopolized the attention of fiction writers.” This touching fable asks us to consider that humans aren’t the only animals with individual lives that matter.

Amitav Ghosh, The Hungry Tide

Tigers in the Sundarbans archipelago are known man-eaters, killing villagers and eating their livestock. In Ghosh’s novel, tigers and human communities clash in this dangerous waterscape. When a marauding tiger is murdered, the predicament is illuminated: If the tiger’s death is to be lamented, what about the deaths of its victims—or are they too poor to matter?

Fiona McFarlane, The Night Guest

Like many tigers, the one in The Night Guest is unseen but vividly felt. Ruth, widowed and slipping, senses him some nights in her house; her cats feel him, too. He’s a dream, but he isn’t. At the same time, a “government carer” arrives and establishes herself as an ever-larger presence in Ruth’s home. This novel—by turns comic and suspenseful—takes on trust, dependence, and the aftereffects of colonialism. If a tiger can be an emissary, this one is it.

Téa Obreht, The Tiger’s Wife

Spooked by falling bombs during the Second World War, a tiger escapes from a zoo and haunts the forest above a village, where he soon forms a bond with a young deaf-mute woman. When she later appears pregnant, villagers deduce that she has become the tiger’s wife. This tiger, whom villagers call the Devil, is less a demon than a mirror for their own war-inflected terrors.

Julio Cortázar, “Bestiary”

In this 1951 tale from Argentina, young Isabel is sent to spend the summer at a home in which a tiger lives. The unseen beast rules the household; before anyone enters a room, someone must determine that the tiger isn’t currently occupying it. But Isabel’s hosts shrug off the predicament; the house has many rooms, after all, and the tiger can only be in one of them. A timeless—and timely—allegory for how we shape our lives to accommodate chaos and repression.

Jorge Luis Borges, “Blue Tigers”

My own book cover features a leaping blue tiger, so inevitably I was drawn to this short story, though its “tigers” are actually blue stones that multiply and disappear spontaneously, horrifying the narrator, who takes their mutability as a curse. Even so, the rumor of actual blue tigers puts the story in motion, and in literature, tigers excel at making things happen.

Rudyard Kipling, The Jungle Book

When I discovered The Jungle Book, I was upset that Shere Khan is cast as Mowgli’s enemy. Shere Khan is vilified for breaking the Law of the Jungle. Born lame, he mostly kills cattle. The other animals call him “Butcher,” but to me, the condemnation rings false.

A. A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner

Tigger is a cheery fellow, if unsure of his identity. Spotting himself in Pooh’s looking-glass, he exclaims, “I’ve found somebody just like me. I thought I was the only one of them.” (Did Milne intend this as a commentary on extinction? Doubtful, but it’s not a bad one.) Like all literary tigers, Tigger is a chaos generator, but an endearing one, cluelessly disrupting the routines and repressions that help other animals feel safe.

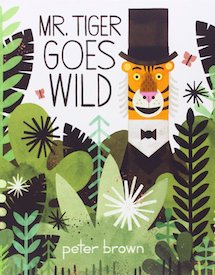

Peter Brown, Mr. Tiger Goes Wild

The thing about repression is that the spirit eventually rebels. In this charming picture book, Mr. Tiger can no longer bear the strictures of his drab Victorian town. Next thing you know, he loses his top hat—then his entire suit of clothes—and takes to the wilderness. But his romps become lonely. Returning to town, he brings his subversive ways back with him; the other town animals see the appeal, and a happy compromise is struck. An Apollonian-Dionysian parable about finding balance where you live.

_____________________________________

Katy Yocom’s Three Ways to Disappear is out now from Ashland Creek Press.

Katy Yocom

Katy Yocom lives in Louisville, Kentucky. Her debut novel, Three Ways to Disappear, is out July 16 via Ashland Creek Press. She holds an MFA from Spalding University, where she serves as associate director of the School of Creative and Professional Writing.