“The San Francisco music scene . . . is first of all the freedom to create here,” Janis said, nine months after her arrival. “Musicians ended up here together [with] the complete freedom to do whatever they wanted to [and] came up with their own kind of music.” In San Francisco, Janis would expand her vocal style and find validation among a new gang: a close-knit group of iconoclasts who’d been on the forefront of an emerging counterculture. Her adopted musical family, Big Brother and the Holding Company, served to provide Janis stability and opportunity, allowing her to forge a unique artistic identity. While simultaneously propelling them to fame, Janis’s voice would become both the key to the struggling band’s success and the reason for its eventual demise. Big Brother was doomed to be left behind. But Janis’s immersion into the Haight-Ashbury scene would culminate in her finding her voice as a new kind of female singer.

On this, her third journey to San Francisco, Janis’s traveling companion did not rush to reach their Emerald City. Much to her delight, Travis Rivers took time to romance Janis along the way. Amorous stops in El Paso, Texas; Juarez, Mexico; and Golden, New Mexico cemented their bond.

“Halfway through New Mexico,” Janis claimed the following year, “I [was] conned into being in the rock business by this guy that was such a good ball. I was fucked into being in Big Brother.” In her origin myth, she downplays her burning ambition to become a successful singer. But in reality, of course, the con artist in her life had been Peter de Blanc, a harrowing tale of which she rarely spoke. Rivers, on the other hand, drove Janis to her destiny and one of her own making.

On Friday, June 3, 1966, they reached San Francisco, where they connected with Helms, recently married to an aspiring actress. He now wore his hair below his shoulders and had cultivated a full beard. With his wire-rimmed glasses and vintage morning coat, he looked like a character from the Old West. He paid $35 a month for Janis’s new home: a room in the run-down Haight-Ashbury district at 1947 Pine Street. When Janis had left in ’65, Pine Street was becoming ground zero of the developing counterculture. Helms fell in with the Family Dog House: communal residents of Pine Street named for their love of canines or possibly their scheme to launder drug-dealing profits into Family Dog, a pet cemetery start-up in a vacant lot that never materialized. The Family Dog began hosting themed rock & roll dances, beginning with “A Tribute to Dr. Strange,” held at the Longshoreman’s Hall on Fisherman’s Wharf, where fun-loving seekers took LSD while partying to bands such as Jefferson Airplane and the Charlatans, founded by Janis’s friends George Hunter and Dan Hicks. By the summer of ’66, the scene had expanded to weekly psychedelic dances at the Fillmore Auditorium and most recently the Avalon Ballroom.

On their second night in San Francisco, Janis and Rivers went to see the Grateful Dead at the Fillmore, an old ballroom located up a rickety staircase in a predominantly black neighborhood. Inside, she joined the swirling bodies, long-haired men and women, dressed in an eclectic mélange of vintage clothing, exotic fabrics, and ethnic garb—“seven different centuries thrown together in one room,” according to one initiate.

“The big dances . . . blow your mind!” is how Janis later described them in a letter home. “Fantastic—the clothes and people! Pure sensuousness . . . bombarding the senses . . . astound[ing] you.” From the Palo Alto folk scene, Janis knew the Dead’s leaders and main vocalists: guitarist Jerry Garcia and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, who played the organ and blues harp. She instantly tuned into the band’s extended blues jams, recognizing “Stealin’, Stealin’ ” and a few other songs. Their loud sonics and the psychedelic light show, projected by Pine Streeter Bill Ham, melding blobs of color onto the band transformed the music into something she’d never experienced. “[It] completely stoned me!” Janis remembered. “Whew!” She hadn’t been so energized since doing the dirty bop in Louisiana roadhouses or so thrilled by a scene since first encountering Austin’s Ghetto.

She tried to downplay her excitement and persuade her parents—and perhaps herself—that she wasn’t diving back into a life that had almost killed her.On Monday morning, June 6, Janis wrote her parents “with a great deal of trepidation” after Jim Langdon informed her that Dorothy had become hysterical when he told her where Janis was. Apologizing for sneaking off to San Francisco, she explained that “Chet Helms, old friend, now is Mr. Big in S.F. Owns 3 big working rock & roll bands with bizarre names like Captain Beef heart & His Magic Band, Big Brother & the Holding Co., etc seems the whole city [has] gone rock & roll and [he] assured me fame & fortune.”

Janis painted a wholesome picture of her road trip west: “camped out at night along the Rio Grande, collected rocks, etc.” She tried to downplay her excitement and persuade her parents—and perhaps herself—that she wasn’t diving back into a life that had almost killed her. She sounded nonchalant about that afternoon’s scheduled first meeting with Big Brother and the Holding Company and joked about the outcome, comparing herself to one of the few female pop stars of the day. “Supposed to rehearse w/ the band this afternoon, after that I guess I’ll know whether I want to stay & do that for awhile. Right now my position is ambivalent—I’m glad I came, nice to see the city, a few friends, but I’m not at all sold on the idea of becoming the poor man’s Cher.”

Evident from the letter is Janis’s concern for her parents’ feelings— and her worries for herself:

I just want to tell you that I am trying to keep a level head about everything & not go overboard w/enthusiasm. I’m sure you’re both convinced my self-destructive streak has won out again but I’m really trying. I do plan on coming back to school—unless, I must admit, this turns into a good thing.

Chet is a very important man out here now & he wanted me specifically, to sing w/this band. I haven’t tried yet, so I can’t say what I’m going to do—so far, I’m safe, well fed, and nothing has been stolen. . . . I’m awfully sorry to be such a disappointment to you. I understand your fears at my coming here & must admit I share them, but I really do think there’s an awfully good chance I won’t blow it this time. There’s really nothing more I can say now….. You can’t possibly want for me to be a winner more than I do.

That afternoon, only her third full day in the city, Janis met Big Brother and the Holding Company for the first time at their Henry Street rehearsal space in an old carriage house built for horse-drawn fire trucks. “It was an organic place,” recalled guitarist Sam Houston Andrew III, who was twenty-four. “People were nursing babies in one corner and making silk screen prints in another.” One of the building’s tenants, artist Stanley “Mouse” Miller—who designed psychedelic posters advertising Family Dog dances and other events with partner Alton Kelley—hailed from Detroit, as did Big Brother’s twenty-six-year-old guitarist James Gurley. From her folkie days, Janis remembered bassist Peter Albin, twenty-two, who had formed the band in spring 1965 with Andrew, then a grad student at the University of California at Berkeley. Originally playing together in a massive Victorian boarding house at 1090 Page Street owned by Albin’s uncle Henry, Big Brother was discovered early on and named by Helms, who charged fifty cents admission to their Wednesday-night jam sessions. He then introduced them to Gurley, who’d been working out his odd tunings alone in a closet. Helms booked the group at clubs and happenings—including San Francisco’s first Trips Festival—and at the Family Dog’s Avalon Ballroom, which he’d opened two months earlier in April. After several personnel changes, Big Brother completed its lineup in March, settling on twenty-six-year-old drummer David Getz, a New York–born artist and Fulbright scholar.

As far back as 1963, James Gurley had heard Janis sing at the Coffee Gallery, where “the strength and power of her voice blew my mind”—around the time that Peter Albin first saw her in Berkeley and Palo Alto. Sam Andrew had never experienced Janis firsthand but had heard of her through friends. Only Getz had no prior knowledge of Janis, and the night before her arrival, he dreamed of a gorgeous woman as their new vocalist.

Janis looked more Texas tomboy than glamorous “girl singer.” Her hair pulled back, she wore denim cutoffs and a baggy shirt, along with a healthy glow. The guys, on the other hand, looked hip, with longish hair and cool clothes: Gurley, in particular, had the air of a shaman, his light brown locks hanging straight down, and his gaunt face and blue eyes projecting quiet intensity; Peter Albin, with a grown-out pageboy and colorful shirt; and Dave Getz, with an unruly dark mop, traded humorous banter. Tall, lanky Sam Andrew, with his chiseled, handsome face and shaggy hair, exuded a friendly warmth. “When I first met Janis, she was not a stranger to me,” he said. “Her accent, her attitudes, even her clothes made her seem like a sister or cousin from my mother’s side of the family, who were all from the same part of Texas as Janis.”

“It was as if she had caught hold of a passing freight train barreling through the night and was not sure if she could hold on.”“I met them all, and you know how it is when you meet someone: you don’t even remember what they look like, you’re so spaced by what’s happening,” Janis recounted. “I was in space city, man. I was scared to death. I didn’t know how to sing the stuff. I’d never sung with electric music, I’d never sung with drums.”

The volume of sound, with the amps cranked up, overwhelmed her at first. “It was as if she had caught hold of a passing freight train barreling through the night and was not sure if she could hold on,” according to Sam Andrew. “She always had a firm grip on the pitch, though— never a sharp or flat moment. She sang really fast, and she talked really fast. Janis always had this thing of total insecurity and total power at the same time, and it was really something to be confronted with both of them. You never knew which one to relate to.”

As they started playing, she realized the guys were treating her like a bandmate rather than an auditioning hopeful. Big Brother had played dozens of shows over the past six months and built an enthusiastic following. But the musicians aspired to the kind of success the six-piece Jefferson Airplane enjoyed. The first of the new bands to score a major record deal, the Airplane had two lead singers, former folkies Marty Balin and Signe Anderson, and the male-female dynamic worked well. An up-and-coming group, the Great Society, also featured a charismatic female singer, Grace Slick. Big Brother wanted a woman’s voice to complement Peter Albin’s baritone. They’d auditioned several, but no one clicked—until Janis. She “knocked us out, instantaneously,” Dave Getz said, and Big Brother welcomed her into the band.

Big Brother’s next show was less than a week away: a double bill with the Grateful Dead at the Avalon. They all knew the 1920s blues “Trouble in Mind” and “C.C. Rider,” and Janis jumped in on vocals. “At first, she sounded like Bessie Smith on a sped-up seventy-eight,” Sam Andrew recalled. “It was very treble very thin, in the upper register, like a tape on fast-forward.” With no experience singing over electric guitars and drums, she quickly altered her style and pitched her vocals to soar over the roaring wall of sound, sometimes shrieking like Roky Erickson of Austin’s 13th Floor Elevators.

“She seemed so scared,” Henry Street resident and scenester Suzy Perry said, “trying to please, wanting so much to belong. I felt so sorry for her.” Janis finally loosened up on the gospel song “Down on Me.” “I’d heard it before and thought I could sing it, and they did all the chords,” she recalled. She secularized “Down on Me,” turning it into a sensual, sultry blues. “Janis changed the lyrics, as well as the way she sang it,” cutting the religious references, said Sam Andrew. “Janis’s voice was right on the money from the first minute she sang with us.”

“Still working w/Big Brother & the Holding Co. & it’s really fun!” she wrote the Joplins later that week, on the eve of her Avalon debut. “Four guys in the group—Sam, Peter, Dave, & James. We rehearse every afternoon in a garage that’s part of a loft an artist friend of theirs owns & people constantly drop in and listen—everyone seems very taken w/ my singing although I am a little dated. This kind of music is different than I’m used to.”

She enclosed an ad for the Avalon gig, clipped from the San Francisco Chronicle, and commented on the scene, intending to humor her family: “Oh, I’ve collected more bizarre names of groups to send—(can you believe these?!) The Grateful Dead, The Love, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Leaves, The Grass Roots Tomorrow night at the [Avalon] dance, some people from Mercury [Records] will be there to hear the Grateful Dead (with a name like that, they have to be good ) and Big Brother et al. And I’m going to get to sing! Gosh I’m so excited! We’ve worked out about 5 or 6 numbers this week— one I really like called ‘Down on Me’—an old spiritual—revitalized and slightly bastardized w/new treatment.”

Janis reassured her parents she was safe and living in a respectable place: “a room in a rooming house. Very nice place w/a kitchen & a living room & even an iron & ironing board. Four other people living here—one schoolteacher, one artist, don’t know the rest.” She also put a positive spin on her chances of success and on the professionalism of Helms’s “corporation,” the Family Dog, even though in reality it personified laid-back hippie disorganization. “Chet Helms heads a rock & roll corporation called the Family Dog—replete w/emblem & answering service. Very fancy. Being my entrepreneur (and mostly having gotten me out here without money—I still have $30 in the bank I’m hoarding), Chet rented me this place for a month. He says if the band & I don’t make it, to forget it, & if we do, we’ll have plenty of money.”

And she told them what they wanted to hear about herself, lying that she was “something of a recluse.” She also dangled the hope that she might return to college and assured them she was not taking speed: “I’m still okay—don’t worry. Haven’t lost or gained any weight & my head’s still fine. And am still really thinking of coming back to school, so don’t give up on me yet.” What Janis didn’t write was that college would be a backup plan if she wasn’t accepted by the band’s hip audience. Dave Getz, who drove her to rehearsals, recalled that she constantly wondered if she was following the right path. “She had a lot of misgivings,” he reflected.

But during rehearsals, Janis learned quickly, experimenting with new vocal techniques. Taking another cue from Roky Erickson, she began to let loose banshee wails when Gurley’s and Andrew’s guitars crescendoed in their improvisational jams. With Peter Albin’s baritone taking the lead in most songs, Janis unleashed high-pitched shrieks as accents. On Big Brother’s sped-up version of “Land of 1000 Dances,” her raspy sound hinted at Wilson Pickett’s soulful version, then on its way into the Top 10. From her teenage days cruising Port Arthur with the radio blasting, Janis already knew some of Big Brother’s rock & roll repertoire: Little Richard’s “Ooh! My Soul” and Shirley and Lee’s “Let the Good Times Roll.” On a twelve-bar blues, such as Tommy Tucker’s “Hi-Heel Sneakers,” Janis pushed her voice as far as she could, trying to avoid sounding “dated” like a coffeehouse folkie. Big Brother twisted blues tunes into another sonic realm so that she barely recognized them: on “I Know You Rider,” originally a 1927 Blind Lemon Jefferson recording, Janis added call-and-response vocals, while James Gurley—nicknamed “Archfiend of the Universe” for his dark, cacophonous guitar style—played atonal, angular leads. Albin kicked off Howlin’ Wolf ’s “Moanin’ at Midnight”; joining in on vocals, Janis added startling yelps. Five days after their first meeting, she was ready for her debut.

The Avalon Ballroom took up the top two floors of a former dance academy on Sutter Street, not far from Janis’s former home at the Goodman Building. Before the venue’s April ’66 opening, Helms had installed fluorescent and strobe lights to accentuate the audience’s Day-Glo-painted skin while partiers glided across burnished wooden floors. From the balcony, Bill Ham’s amoeba-shaped projections provided the only stage lighting.

On Friday, June 10, “We boys came out and did our insane, free-jazz, speedy clash jam,” Sam Andrew recalled of Janis’s opening night. Then, after their first few numbers of “freak rock,” Janis strolled onstage, taking her place next to Peter Albin, who nonchalantly told the crowd, “Now we’d like to introduce Janis Joplin.” “Nobody had ever heard of fuckin’ me,” Janis recounted later. “I was just some chick, didn’t have any hip clothes or nothing like that. I had on what I was wearing to college. I got onstage and I started singing—whew!”

The crowd, already under the influence of the sonic barrage, focused mostly on Gurley’s Les Paul guitar. “He played out there,” said Bill Ham. With Ham’s light show projecting color onto Gurley’s skinny physique, his abstract noodlings riveted the stoned audience. But when Janis began to move rhythmically, shaking her tambourine, and belted “Down on Me,” the audience was instantly transfixed.

“What a rush, man! A real, live drug rush!” Janis recalled vividly of the moment. “All I remember is the sensation—what a fuckin’ gas, man! The music was boom, boom, boom, and the people were all dancing, and the lights, and I was standing up there singing into the microphone and getting it on, and whew! I dug it! I said, ‘I think I’ll stay, boys.’ ”

She had transformed herself from self-conscious folk-blues singer to emotive, sensual performer.From that night on, Janis’s world revolved around Big Brother. She “was fabulous,” Helms said of her debut. “The audience concurred; they’d never heard anything like it.” Near-daily rehearsals followed, with Janis, having passed “the test,” being further integrated into the group. A quick study, she diligently jotted down lyrics, and the band adjusted its approach to make room for the dynamic new vocalist. “We started trying to sing harmonies with Janis, and we added very defined beginnings and endings to our songs,” according to Dave Getz. The musicians shortened some of their lengthy improvisations to accommodate her singing, while Janis expanded her vocal palette, veering from high-pitched shrieks, to gospel-inspired testifying, to Bessie Smith blues. Big Brother valued democracy, with each member except Getz taking vocal turns, so that Janis sang lead only on four or five numbers, while adding harmonies to the guys’ songs.

Two weeks after her June debut, Big Brother returned to the Avalon for a weekend of gigs—two shows each night. The first of several bookings over the next few months, the evening set the pattern for Janis’s new life. Onstage, she grew less inhibited with each appearance. Chet Helms compared her with the performer he’d seen only a short time before in coffeehouses: “Suddenly this person who would stand upright with her fists clenched was all over the stage. Roky Erickson had modeled himself after the screaming style of Little Richard, and Janis’s initial stage presence came from Roky, and ultimately Little Richard. It was a very different Janis.”

She had transformed herself from self-conscious folk-blues singer to emotive, sensual performer. Soon her impassioned vocals drew audiences to the lip of the stage. “I couldn’t stay still,” Janis explained later. “I had never danced when I sang; just the old sit-and-pluck blues thing. But there I was moving and jumping. I couldn’t hear, so I sang louder and louder. You have to sing loud and move loud with all that in back of you.” Peter Albin continued as front man, making arch or absurd comments. Janis would lean over and banter, “What are you talking about?” as she played tambourine.

The 800-capacity Avalon filled with Big Brother fans and the curious at $2 each. “The whole environment was the show,” said Helms. The crowd was “as key an element of the performance as the musicians themselves.” On the low, unlit stage, the band blended with listeners, which leant a casual intimacy that helped Janis feel comfortable. “There was this sense you were part of the audience,” Getz said, “and the vibe of the audience and the energy they gave you and that you gave the audience was an interactive thing. Everybody got a high.” Janis had found her tribe—and herself. “When I sing, I feel, oh, like when you’re first in love,” she’d tell a journalist the following year. “Like when you’re first touching somebody. Chills, things slipping all over me. It was so sensual, so vibrant, loud, crazy!”

Fellow musicians were duly impressed by Janis’s talent. Though the stage had no monitor speakers to aim the sound back at the performers, she managed usually to stay on key—a rarity for most local singers— and yet be heard over the band’s roaring guitars. Her old friend Jorma Kaukonen, now the lead guitarist of Jefferson Airplane, brought bandmate Jack Casady to check out Janis.

“The first time I heard her sing,” recalled the bassist, “she was just fantastic—one of the few white singers who could sing the blues well.

She hit that Bessie Smith genre right on the money, hit it solid.” Casady, a rabid record collector, would eventually give Janis the R&B song that would take her to the Top Ten.

Janis soon began forming a personal bond with her bandmates. Albin, married with a young daughter, was a bit standoffish, but she became close to Dave Getz and the others. “We made out in the back seat of my car, three or four times,” Getz recounted. “I thought maybe we’d have something, but she didn’t want to get involved with me sexually. At one point, she said, ‘No, I can’t do this. I’ve gotta go.’”

She and Travis Rivers were still “sweethearts,” according to Rivers, but they were drifting apart. Living on Pine Street, where she used to buy drugs, Janis worried about crossing paths with speed freaks and dealers. “She was very afraid of drugs,” Getz recalled. “She said, ‘I don’t ever want to see anybody shooting drugs.’” Then one night, when she discovered Rivers and a friend hitting up in their room, she freaked out. Apologizing, Travis claimed they were injecting mescaline, not speed, but Janis was furious. “She was easily bruised,” Rivers said. “I had hurt her feelings once before, and I had to hold her in the air over my head with her arms facing away from me so she wouldn’t hurt me. She was screaming. I never forgave myself for it.”

Trying to win her back, he proposed marriage the next day, but she turned him down. Certainly thoughts of Peter de Blanc’s betrayal and false promises were still fresh. “She said, ‘I’m about to become incredibly famous and will have access to any boy I want,’ ” Rivers recalled, “‘and I want to take advantage of it.’ ” In the four years he’d known Janis, he had experienced her “two sides,” he explained. “A perfectly sweet, wonderful, well-bred, lace-curtain girl”—the Janis that craved the white picket fence. Her other side, the rowdy, cackling “West Texas cowgirl/sailor persona—which she presented when she was unsure of how she was going to be accepted. That was the side she used onstage.”

__________________________________

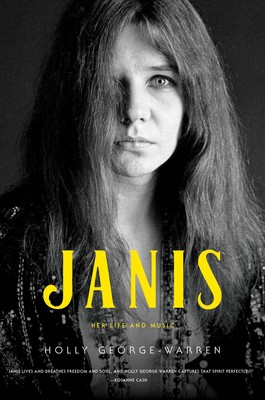

From Janis: Her Life and Music by Holly George-Warren. Copyright © 2019 by Holly George-Warren. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.