The Boundaries Between Nations Are Blurrier Than We Think

Oliver Uberti and James Cheshire on the Myth of Foundational Nationalism

Ancient DNA shows nationalism is only a state of mind.

Over the past decade, geneticists in labs around the world have been extracting DNA from ancient human remains. Each sequenced strand adds to a map of genomic composition over time. In lieu of delineating national borders, its purpose is to connect dots and solve mysteries such as “Who made Stonehenge?” Many in Britain may believe the monument was the work of their ancestors. DNA samples now prove that at the time the megalith builders broke ground on Salisbury Plain, the primary forebears of today’s northern Europeans had not yet entered the picture. In fact, most Europeans owe a large percentage of their DNA to a group of people they have likely never heard of: the Yamnaya. Five thousand years ago, these nomadic herders flourished on the Steppe, a belt of harsh, dry grassland stretching between the Altai Mountains to the east and the Danube River to the west. The secret to their spread? The wheel.

The Yamnaya tamed horses, built wagons and followed the grasslands west, bringing their genes and language across Europe. Ancient DNA indicates that another contingent arced east and down through central Asia to the Indus Valley.

These genetic trails challenge notions of national purity. Before mixing with early Europeans and South Asians, the Yamnaya were themselves a mixture of earlier Steppe peoples and groups pushing north from the Caucasus Mountains. So it’s no great cognitive leap to view human history as one continuous series of mixture from time immemorial to the present.

Within a few hundred years after Stonehenge’s last Sarsen stone was hoisted into place around 2500 BCE, the genetic data of the hoisters was almost entirely overwritten.

Unlike in Britain, the Yamnaya didn’t overwrite the Indian subcontinent as much as partition it. Their arrival pushed earlier inhabitants south into communities that bear no trace of Yamnayan ancestry.

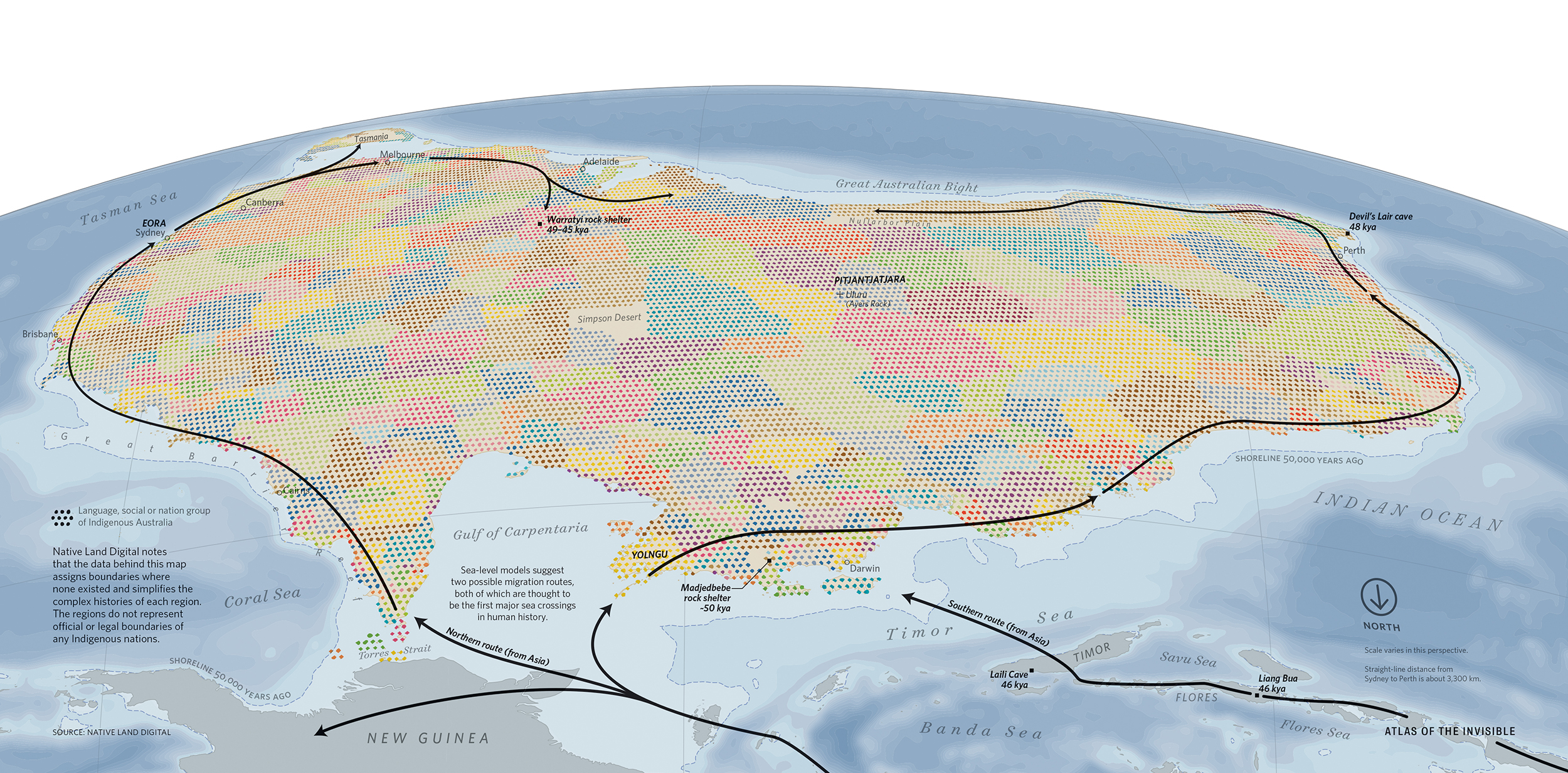

The “great southern land” was home to millions before Europeans arrived.

The first people to set foot on the shores of Australia arrived about fifty thousand years ago, when sea levels were 75 meters (246ft) lower. Back then, the Gulf of Carpentaria and the Torres Strait were a savanna that extended from Australia’s northern coast to New Guinea. DNA from hair samples shows that the donors’ ancestors took between one and five thousand years to migrate both clockwise and counterclockwise to the south coast of the continent we know today. Individual communities soon emerged that included the Pitjantjatjara who live beside Uluru, the sacred sandstone landmark, the Yolngu with their distinctive sign language and the Torres Strait Islanders famous for their ceremonial headdresses— cultures that existed for millennia before British settlers showed up near the end of the eighteenth century.

The establishment of Sydney in 1788, on the lands of the Eora, was but the first stroke in a two-century effort to whitewash the diversity on this map. The First Australians were subjected to European diseases, land appropriation and even a policy of child removal that continued to the 1970s.

Today, Native Land Digital, a Canadian nonprofit, hosts an online, interactive map of Australia’s 392 Indigenous territories to inform discussions about land rights, language and local history. They’ve added Indigenous boundaries for other countries too, so readers in Japan, New Zealand (Aotearoa), Russia, Scandinavia and the Americas can acknowledge what ancestral land they inhabit.

Native Land Digital notes that the data behind this map assigns boundaries where none existed and simplifies the complex histories of each region. The regions do not represent official or legal boundaries of any Indigenous nations.

Sea-level models suggest two possible migration routes, both of which are thought to be the first major sea crossings in human history.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Atlas of the Invisible: Maps and Graphics That Will Change How You See the World by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti. Copyright © 2021 by James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti

James Cheshire is professor of geographic information and cartography at University College London.

Oliver Uberti is a Los Angeles–based designer and a former design editor for National Geographic.