The Books That Mattered Most to David Bowie, Bibliophile

Literary Influences, From Nietzsche to Mishima

David Bowie once recounted a story from the filming of The Man Who Fell to Earth in 1975. Relocating from Los Angeles to New Mexico for the shoot, he brought hundreds upon hundreds of books with him, a “traveling library” that he ported in cases large enough to hold an amplifier. His director, Nicolas Roeg, seeing Bowie sifting through piles of books, told him that “your great problem, David, is that you don’t read enough.” Bowie said he didn’t realize for months that Roeg was joking. Instead he berated himself, asking “What else should I read?”

Not the typical 1970s rock star anecdote. Throughout his life, Bowie was a colossal bibliophile, with books as the one habit he never relinquished. When he wasn’t recording or touring, he appears to have spent much of his days reading. Late in life, he was a regular sighting at his local bookstore, McNally Jackson in Soho, and a photograph taken of him in 2013 parallels his Man Who Fell to Earth story. Again, Bowie’s sitting on the floor surrounded by stacks of his books, here including Geeta Dayal’s Another Green World and Stephen Fry’s The Ode Less Travelled.

Many rock songs have been hatched from books: “Sympathy for the Devil” (Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita); Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights”; the Mekons’ “Only Darkness Has the Power” (Paul Auster’s The Locked Room) and so forth. But Bowie’s catalog is particularly rife with songs indebted to fiction and nonfiction, to short stories and (laughing) gnomic philosophical treatises. He even wrote lyrics via a literary device—William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin-style cut-up, where he’d scissor up a page from, say, a novel that he was reading and use randomly-selected text strips to kick-start a verse. (By the 1990s, he had software do the grunt work for him.)

It’s telling that among Bowie’s final public statements was a list of his Top 100 books, offered as part of the David Bowie Is museum exhibit. As Bowie has apparently left no memoir behind, the closest that he ventured to autobiography is this list of books. Some he chose because he wanted his fans to read them, but many selections have a deeper resonance in his work.

The following are some books that influenced Bowie’s songwriting, from his early records in the 1960s to his last albums.

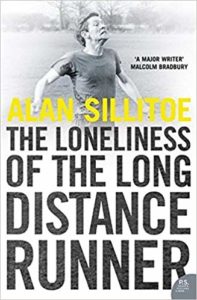

Alan Sillitoe, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner

Bowie’s 1967 debut greatly consists of third-person narrative songs: the most “realist” work, lyrically, he’d ever do. At age 19, he was consumed with the “Angry Young Men” British authors, with John Braine’s Room at the Top, Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar and There Is a Happy Land and John Osbourne’s Look Back in Anger among his favorites (the latter two would title Bowie songs). But the most influential was Alan Sillitoe’s 1959 short story collection, which Bowie raided for early songs. He used the plot of Sillitoe’s “Uncle Ernest” for his “Little Bombardier,” while his own “Uncle Arthur” came from elsewhere in Sillitoe’s collection, “The Disgrace of Jim Scarfedale.”

Henrich Harrer, Seven Years In Tibet

Bowie discovered Buddhism in the mid-1960s, befriending exiled Tibetan lamas in London and devouring Heinrich Harrer’s 1952 memoir. Harrer had lived in Tibet at a time when few Westerners had ever ventured there, and documented its last days as an independent kingdom before the Chinese conquest. Harrer’s depictions of the Dalai Lama’s Potala palace would shape Bowie’s 1967 “Silly Boy Blue,” the song of a dreaming monk in Lhasa. And decades later, Bowie named a song on his Earthling album after Harrer’s book. In his own “Seven Years in Tibet,” Bowie returned in the mid-1990s to find a land still under the tyrant’s heel, still dreaming resistance.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Though he once joked that he’d only read the book jacket of Nietzsche’s ode to the overman, Bowie was being modest. Zarathustra would be central to shaping Bowie’s work in the late 1960s and early 1970s—he’d quarry images from it for songs including “All the Madmen,” “The Supermen,” “Quicksand,” and “Ashes to Ashes.”

Arthur C. Clarke, Childhood’s End

Clarke’s 1953 SF novel of a race of alien beings who come to Earth to midwife the next step in human evolution has echoes in Bowie’s generational “changing of the guard” songs of the early 1970s, particularly “Oh! You Pretty Things” and “Changes.”

Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Though more inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film of Anthony Burgess’ novel, with Droog uniforms as a template for Spiders From Mars stage outfits, Bowie was also fascinated by Burgess’ invented “Nadsat” language for his narrator’s voice. It inspired his own attempts in the 1970s to create a “fake world…that hadn’t happened yet.” Decades later, on his last album, Bowie wrote a funny, nasty song chock full of Nadsat (“Girl Loves Me”).

Nik Cohn, I Am Still the Greatest Says Johnny Angelo

Nik Cohn, I Am Still the Greatest Says Johnny Angelo

“Violence and glamour and speed, gesture and combustion, these were the things he valued—none else.” Cohn’s 1967 portrait of a rock star/force of chaos, based in part on Elvis and P.J. Proby, heralds the plastic rocker “leper messiah” that Bowie created. Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane are inconceivable without it.

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Up there with A Clockwork Orange in terms of books that Bowie couldn’t leave alone. He tried to write a musical based on it and though being denied the rights by Sonia Orwell, basically did it anyway with Diamond Dogs. He later said that Orwell’s world had felt like his own upbringing in postwar Brixton and Bromley, and throughout his life Bowie returned to images of people trapped in systems of control, whether those of religion or government.

Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind

MIND YOUR BICAMERAL/ YOUR BICAMERAL MIND, Bowie etched into the runout groove of his 1979 “Boys Keep Swinging” single, along with a lyre symbol. Jaynes’ 1976 treatise argued that the brain’s two lobes were once isolated, so early humans “heard” thoughts from one lobe as the voices of gods—it was the sort of compelling crackpot theory that Bowie loved. “The speaker was an angel,” he sang in “Look Back in Anger,” a possible reference to Jaynes’ claim that the emergence of angels, ca. 1000 BC, was a sign the barriers between the brain’s halves were breaking down.

Otto Friedrich, Before the Deluge: A Portrait of Berlin in the 1920s

Bowie lived in West Berlin in the late 1970s and spent his time there as a literary reenactor. He yearned to be in the Berlin of Christopher Isherwood’s novels, to the point of even looking at times like Michael York’s character in Cabaret. One tourist guide was Friedrich’s portrait of Weimar Berlin, a doomed city of exiles, revolutionaries and artists. Bowie would later use a Vladimir Nabokov quote from Friedrich’s book in “I’d Rather Be High.”

Hans Richter, Dada: Art and Anti-Art

When Bowie was cutting Scary Monsters in 1980, he had Dadaist artists on the brain, telling an interviewer that as the Dadaists had said art was dead in 1924, “what the hell can we do with it from there on”? This sense of “lateness” and struggle pervaded his album. He was taken with Dadaist artist Richter’s 1964 study, to the point where he nicked whole lines from it for “Up the Hill Backwards.”

Peter Ackroyd, Hawksmoor

Ackroyd’s novel, with its interwoven narratives of an occultist architect in 18th Century London who consecrates his churches with human sacrifices, and a 20th Century “rationalist” detective, is deep in the roots of Bowie’s “art murder” mystery album, 1.Outside.

Yukio Mishima, Spring Snow (The Sea of Fertility Quartet)

Japanese author Yukio Mishima was among Bowie’s favorites, with the former’s The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea found in everything from “Heroes” to Bowie’s regular internet pseudonym “sailor.” And “Heat,” the closing track of The Next Day, opens with a reference to Spring Snow, the first part of Mishima’s last work, the Sea of Fertility quartet, whose thematic concerns of reincarnation, glamour, decadence, death and transformation are in Bowie’s late albums as well.

Lawrence Weschler, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonders

It opens with Weschler stumbling upon David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology, a storefront museum in Culver City, California, whose exhibits include “piercing devil” bats and horned African “stink ants.” Intrigued, Weschler chronicles the bizarre holdings of Wilson’s collection. He soon finds that listed details have little connection with scientific fact. Is Wilson a fraud? Is the collection itself Weschler’s fiction? Walking the thin line between magic and science, gifted con men and obsessive curators, strange truth and honest fakery, Mr. Wilson invokes the work of David Bowie as much as anything did.

Chris O'Leary

Chris O'Leary is a writer, editor and journalist based in western Massachusetts and the author of Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie, 1976-2016.. O'Leary has interviewed everyone from Richard Fuld, former head of Lehman Brothers, to Kiefer Sutherland. He writes for Entertainment Weekly as well as the Encyclopedia Britannica. Rebel Rebel, the first of two volumes, is based on the popular music blog "Pushing Ahead of the Dame," which O'Leary began in July 2009