The Book That Changed My Life: Giving Voice to the Divine, Inexplicable Ocean

Jock Serong on the Writing of the Reclusive James Hamilton Paterson

In the early summer of 1994, I walked into Alice’s Bookshop in North Carlton; a small shop in an old terrace on a straight boulevard that runs north out of Melbourne, Victoria. Being so close to the venerable sandstone of Melbourne University, there’s an old-fashioned gravity about the place. It’s musty and crammed with precisely ordered spines, heavy on science and bearded contrarians. Prices are marked in soft pencil on the flyleaf. They do not giftwrap.

That long-ago day, I walked in a bored and restless final-year law student. Moments later I walked out with a used paperback in my hand, and I was no longer the same person.

The book was Seven Tenths: The Sea and its Thresholds, by James Hamilton-Paterson. Published in 1992, it attracted little fanfare, principally because its author was a recluse who refused to do publicity. His Wikipedia entry offers a link to an official website. The link is broken, and that pleases me.

Hamilton-Paterson was born in England to doctor parents, notably a neurologist father who was remote and constantly exhausted. Their relationship was difficult. James became a wanderer and has spent the majority of his life in Tuscany, Austria and the Philippines—specifically, in a hut in the Marinduque jungle beside a lagoon and a coral reef. He was a hospital orderly, a teacher, a musician. Horrifyingly, he was raped by a group of men in Libya, and later wrote of the experience. He writes of many things, always with a piercing melancholy that is extremely hard to describe. He never married nor fathered children. But he is said to be wonderful company, a witty and combative conversationalist.

Seven Tenths is a meditation on the ocean, a book that answered questions that were troubling me in my twenties. The book, like the writer and his style, evades definition, but it weaves together science and history, literature and music, mythology and dreams and more, to establish a deep human connection to the sea; one we cannot ever understand but are obliged to re-enact, down through the centuries. In some ways, also, it is a book about drowning.

My prospects there were safe and soporific: they housed my family and all of my friends. But I was desperate to spend my days in, and on, and near to, the ocean.

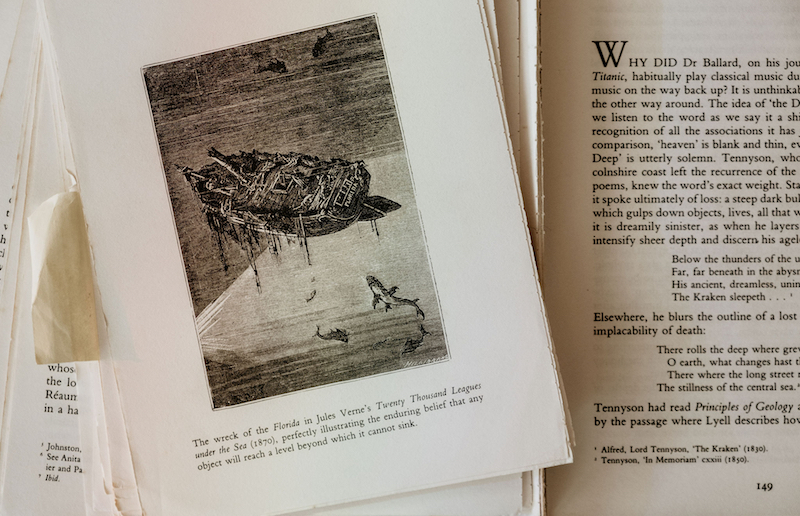

There’s a passage in there, complete with antique lithograph, about the surprisingly persistent belief that sunk objects would stop in the water column at a depth which corresponded to the relationship between their weight and the density of the water. That is, in deep enough seas, shipwrecks would just hang there, suspended for all eternity. There’s an exploration of the longstanding scientific confusion about the true nature of corals, evoking the timeless image of naturalists winching up loads of colorful formations from the seabed, only to have them rot to stinking putrefaction in the hold of the ship.

It gave form to an ache I felt. I grew up in the suburbs of Melbourne. They spread, flat and unremarkable for miles in every direction: there is no landform to block their spillage. Though they are heedlessly piled on top of the material remains of the oldest living culture on the planet, they carry no great history of their own. They are the suburbs of any metropolis: mortgages and supermarkets, restless teenagers and letterboxes. My prospects there were safe and soporific: they housed my family and all of my friends. But I was desperate to spend my days in, and on, and near to, the ocean.

Photo by Jock Serong

Photo by Jock Serong

Melbourne’s suburbs wrap around a large, tranquil bay but it was not the ocean. Not in the dramatic sense I understood it to exist. The real ocean was over an hour away, and although my generous parents would drive me to it on occasional weekends, it remained a faraway realm and the longing burned. As I sat in the library or played football or rode my bike down the lanes behind the shops, I knew that it was out there tearing a cliff off the face of the continent. Hamilton-Paterson had thought about this longing, I discovered. The ways I expressed it on my occasional forays—surfing, or fishing or diving—were mere symptoms, he taught me. The actual causes were as deep as the human soul.

I found good work as a lawyer, but it drove me to despair. I left Melbourne, then returned, tried the desert, fled to the coast again. I’m still there now. The death knell to my legal career, my final capitulation to the lure of the sea, was my involvement in a magazine project called Great Ocean Quarterly, a journal that was an attempt to collect the artistic manifestations of that same obsession: photography, writing, art. In my first editorial for GOQ, I wrote about Hamilton-Paterson and his book, and I hunted down his email address to tell him what I was doing and how he’d altered the course of my life.

He wrote back, brief but friendly. His words were shot through with that same melancholy, focused in 2013 on his sadness that the darkest ecological predictions in his 1992 book had come to pass—and worse—as the world ignored his insights. I wondered as I read his words—why had I contacted him in the first place? Was it the simple courtesy of letting him know I was discussing him in an editorial? Was it the challenge of finding someone who appears and vanishes like a literary mirage? Or was it, somewhere underneath it all, about going back to the seer and finding out what he sees now? The reassuring myth that some thinkers exist outside the fray, enlightened by isolation, and can see patterns in the chaos?

He made it alright to believe in something ethereal about the ocean, something divine and inexplicable that defied both cliché and evidence.

You are wondering why I haven’t quoted his correspondence. Infuriatingly, that exchange of email has disappeared with an old email address. Nothing disappears anymore: everything leaves footprints. It is testament to the evanescent quality of his utterances that this too is gone.

Hamilton-Paterson still leaves a thin trail these days. He has written for magazines, written about the Philippines, and has crafted beautiful poems and novels, most notably the eerie and lyrical Gerontius and Griefwork, neither of which is centrally concerned with the sea. If one of his contributions to my life was an encouragement to salt-seeking nomadism, the other was a lifelong suspicion of publicity-seekers. He is a loner who writes not for fame, but because he needs to. He made it alright to believe in something ethereal about the ocean, something divine and inexplicable that defied both cliché and evidence. With his strange and unsettling prose, he whispered the terrifying possibility, straight-faced, that you could sacrifice your rational life to it.

And here we enter the murkiest territory in any discussion of humans and the sea. For every Hamilton-Paterson; for every surfer, sailor or idle ponderer, there are hundreds of others for whom the sea is not an adventurer’s tabula rasa but a desperate escape from the land. The tragic necessity to seek asylum by sea has always existed, but as a global mass-movement it largely post-dates Hamilton-Paterson’s work. Yet it feels like a topic over which he would have agonized. There is a hint of this concern in his dedication of the book: to the memory of Ben Chong and Arnel Julao, last seen on 20 December 1987 hoping to stow away aboard M/V Dona Paz in order to join their families for Christmas. Who were Ben and Arnel? Were they refugees? Was it mere adventure they sought? As with so many of Hamilton-Paterson’s enigmatic references, the internet is silent on the matter.

Photo by Jock Serong

Photo by Jock Serong

The great moral silence of the ocean, its insistence that the choices are ours, has become a preoccupation in my work. I wrote a novel, On the Java Ridge, about asylum seekers trying to reach Australia through Indonesia, and their accidental entanglement with Australian surfers on holiday. In part, this idea was a reflection of an experience I had on the Atlantic island of Madeira back in 1999: seeing an old village woman scolding some loud, happy Californian surfers for “playing in the water that took my husband.” The sea doesn’t commemorate like the land does: it effaces everything, and under an easy sun we’re complacent again. The coasts around my home in western Victoria, stormy and remote, are littered with shipwrecks. On some days, under particular conditions, the causes of those disasters are readily understandable. This is the day that that would have happened. Exactly this wind and precisely that rock. On others, the tragedies seem laughably improbable.

As he aged, he wrote, he noticed he was letting go of the rock sooner and sooner. He could measure his physical decline by the inhabitants of the reef, peering back at him.

My copy of Seven Tenths is ragged now. The spine is broken, and the pages fall out: it’s held together with rubber bands. It’s less than half as old as I am, and I suppose my own binding is buggered. There is a passage in the book about ageing: he tells of a ritual of his: he would row a small boat out from his home in the Philippine jungle, across the lagoon to the fringing reef, where the coral plunges away into the blue-black of the fathomless ocean. (Elsewhere in the book, he calls depth “time’s liquid correlative,” a perfect instance of his ability to merge physics and mysticism).

He’d moor the boat and dive overboard holding a small rock, spearing down beside the cliff of the reef until his lungs could take no more, then drop the rock and return to the surface. As he aged, he wrote, he noticed he was letting go of the rock sooner and sooner. He could measure his physical decline by the inhabitants of the reef, peering back at him. He would be seventy-eight now, out there somewhere, living in exquisite literary exile.

__________________________________

From The Burning Island by Jock Serong. Used with the permission of Text Publishing. Copyright © 2020 by Jock Serong.

Jock Serong

Jock Serong is an award-winning novelist who lives with his family in Port Fairy. His latest novel, The Burning Island, is out through Text Publishing in September.