Old Peabody and Young Whiffle, partners in the firm of Whiffle and Peabody, Incorporated, read with mild interest the first article about Bedford Abbey which appeared in the Boston papers. But each day thereafter the papers printed one or two items about this fabulous project. And as they learned more about it, Old Peabody and Young Whiffle became quite excited.

For Bedford Abbey was a private chapel, a chapel which would be used solely for the weddings and funerals of the Bedford family–the most distinguished family in Massachusetts. What was more important, the Abbey was to become the final resting-place for all the Bedfords who had passed on to greater glory and been buried in the family plot in Yew Tree Cemetery. These long-dead Bedfords were to be exhumed and reburied in the crypt under the marble floor of the chapel. Thus Bedford Abbey would be officially opened with the most costly and the most elaborate funeral service ever held in Boston.

As work on the Abbey progressed, Young Whiffle (who was seventy-five) and Old Peabody (who was seventy-nine) frowned and fumed while they searched the morning papers for some indication of the date of this service.

Whiffle and Peabody were well aware that they owned the oldest and the most exclusive undertaking firm in the city; and having handled the funerals of most of the Bedfords, they felt that, in all logic, this stupendous funeral ceremony should be managed by their firm. But they were uneasy. For Governor Bedford ( he was still called Governor though it had been some thirty years since he held office) was unpredictable. And most unfortunately, the choice of undertakers would be left to the Governor, for the Abbey was his brain-child.

A month dragged by, during which Young Whiffle and Old Peabody set an all-time record for nervous tension. They snapped at each other, and nibbled their fingernails, and cleared their throats, with the most appalling regularity.

It was well into June before the Governor’s secretary finally telephoned. He informed Old Peabody, who quivered with delight, that Governor Bedford had named Whiffle and Peabody as the undertakers for the service which would be held at the Abbey on the twenty-first of June.

When the Bedford exhumation order was received, Old Pea body produced an exhumation order for the late Louella Brown. It had occurred to him that this business of exhuming the Bedfords offered an excellent opportunity for exhuming Louella, with very little additional expense. Thus he could rec tify a truly terrible error in judgment made by his father, years ago.

“We can pick ’em all up at once,” Old Peabody said, handing the Brown exhumation order to Young Whiffle. “I want to move Louella Brown out of Yew Tree Cemetery. We can put her in one of the less well-known burying places on the out skirts of the city. That’s where she should have been put in the first place. But we will, of course, check up on her as usual”

“Who was Louella Brown?” asked Young Whiffle.

“Oh, she was once our laundress. Nobody of importance,” Old Peabody said carelessly. Though as he said it he wondered why he remembered Louella with such vividness.

Later in the week, the remains of all the deceased Bedfords, and of the late Louella Brown, arrived at the handsome estabishment of Whiffle and Peabody. Though Young Whiffle and Old Peabody were well along in years, their research methods were completely modem. Whenever possible they checked on the condition of their former clients and kept exact records of their findings.

The presence of so many former clients at one time–a large number of Bedfords and Louella Brown–necessitated the calling in of Stuart Reynolds. He was a Harvard medical student who did large-scale research jobs for the firm, did them well, and displayed a most satisfying enthusiasm for his work. It was near closing time when Reynolds arrived at the imposing brick structure which housed Whiffle and Peabody, Incorporated.

Old Peabody handed Reynolds a sheaf of papers and tried to explain about Louella Brown, as tactfully as possible.

“She used to be our laundress,” he said. “My mother was very fond of Louella, and insisted that she be buried in Yew Tree Cemetery.” His father had consented –grudgingly, yes, but his father should never have agreed to it. It had taken the careful discriminatory practices of generations of Peabodys, undertakers like himself, to make Yew Tree Cemetery what it was today –the final home of Boston’s wealthiest and most ar istocratic families. Louella’s grave had been at the very tip edge of the cemetery in 1goz, in a very undesirable place. But just last month he had noticed, with dismay, that due to the enlargement of the cemetery, over the years, she now lay in one of the choicest spots–in the exact center.

Before Old Peabody spoke again he was a little disconcerted, for he suddenly saw Louella Brown with an amazing sharpness. It was just as though she had entered the room –a quick moving little woman, brown of skin and black of hair, and with very erect posture.

He hesitated a moment and then he said, “She was–uh–uh–a colored woman. But in spite of that, we will do the usual research.”

“Colored?” said Young Whiffle sharply. “Did you say ‘colored’? You mean a black woman? And buried in Yew Tree Cemetery?” His voice rose in pitch.

“Yes,” Old Peabody said. He lifted his shaggy eyebrows at Young Whiffle as an indication that he was not to discuss the matter further. “Now, Reynolds, be sure and lock up when you leave.”

Reynolds accepted the papers from Old Peabody and said, “Yes, sir. I’ll lock up.” And in his haste to get at the job he left the room so fast that he stumbled over his own feet and very nearly fell. He hurried because he was making a private study of bone structure in the Caucasian female as against the bone structure in the female of the darker race, and Louella Brown was an unexpected research plum.

Old Peabody winced as the door slammed. “The terrible en thusiasm of the young,” he said to Young Whiffle.

“He comes cheap,” Young Whiflle said gravely. “And he’s polite enough.”

They considered Reynolds in silence for a moment.

”Yes, of course,” Old Peabody said. ”You’re quite right. He is an invaluable young man and his wages are adequate for his services.” He hoped Young Whiffle noticed how neatly he had avoided repeating the phrase “he comes cheap.”

“‘Adequate,'” murmured Young Whiffle. “Yes, yes, ‘adequate.’ Certainly. And invaluable.” He was still murmuring both words as he accompanied Old Peabody out of the building.

Fortunately for their peace of mind, neither Young Whiffle nor Old Peabody knew what went on in their workroom that night. Though they found out the next morning to their very great regret.

It so happened that the nearest approach to royalty in the Bedford family had been the Countess of Castro ( nee Elizabeth Bedford). Though neither Old Peabody nor Young Whiffle knew it, the countess and Louella Brown had resembled each other in many ways. They both had thick glossy black hair. Neither woman had any children. They had both died in 1902, when in their early seventies, and been buried in Yew Tree Cemetery within two weeks of each other.

Stuart Reynolds did not know this either, or he would not have worked in so orderly a fashion. As it was, once he entered the big underground workroom of Whiffle and Peabody, he began taking notes on the condition of each Bedford, and then carefully answered the questions on the blanks provided by Old Peabody.

He finished all the lesser Bedfords, then turned his attention to the countess.

When he opened the coffin of the countess, he gave a little murmur of pleasure. “A very neat set of bones,” he said. “A small woman, about seventy. How interesting! All of her own teeth, no repairs.”

Having checked the countess, he set to work on Louella Brown. As he studied Louella’s bones he said, “Why how ex tremely interesting!” For here was another small-boned woman, about seventy, who had all of her own teeth. As far as he could determine from a hasty examination, there was no way of telling the countess from Louella.

“But the hair! How stupid of me. I can tell them apart by the hair. The colored woman’s will be–” But it wasn’t. Both women had the same type of hair.

He placed the skeleton of the Countess of Castro on a long table, and right next to it he drew up another long table, and placed on it the skeleton of the late Louella Brown. He meas ured both of them.

“Why, it’s sensational!” he said aloud. And as he talked to himself he grew more and more excited. “It’s a front page story. I bet they never even knew each other and yet they were the same height, had the same bone structure. One white, one black, and they meet here at Whiffle and Peabody after all these years–the laundress and the countess. It’s more than front page news, why, it’s the biggest story of the year–”

Without a second’s thought Reynolds ran upstairs to Old Peabody’s office and called the Boston Record. He talked to the night city editor. The man sounded bored, but he listened.

Finally he said, “You got the bones of both these ladies out on tables, and you say they’re just alike. Okay, be right over–”

Thus two photographers and the night city editor of the Boston Record invaded the sacred premises of Whiffle and Peabody, Incorporated. The night city editor was a tall, lank individual, and very hard to please. He no sooner asked Reynolds to pose in one position than he had him moved, in front of the tables, behind them, at the foot, at the head. Then he wanted the tables moved. The photographers cursed audibly as they dragged the tables back and forth, turned them around, side ways, lengthways. And still the night city editor wasn’t satis fied.

Reynolds shifted position so often that he might have been on a merry-go-round. He registered surprise, amazement, pleasure. Each time the night city editor objected.

It was midnight before the newspapermen said, “Okay, boys, this is it.” The photographers took their pictures quickly and then started picking up their equipment.

The newspaperman watched the photographers for a mo ment, then he strolled over to Reynolds and said, “Now –uh sonny, which one of these ladies is the countess?”

Reynolds started to point at one of the tables, stopped, and let out a frightened exclamation. “Why, His mouth stayed open. “Why– I don’t know!” His voice was suddenly frantic. “You’ve mixed them up! You’ve moved them around so many times I can’t tell which is which–nobody could tell–”

The night city editor smiled sweetly and started for the door. Reynolds followed him, clutched at his coat sleeve. “You’ve got to help me. You can’t go now,” he said. “Who moved the tables first? Which one of you–” The photographers stared and then started to grin. The night city editor smiled again.

His smile was even sweeter than before.

“I wouldn’t know, sonny,” he said. He gently disengaged Reynolds’ hand from his coat sleeve. “I really wouldn’t know–”

It was, of course, a front page story. But not the kind that Reynolds had anticipated. There were photographs of that marble masterpiece, Bedford Abbey, and the caption under it asked the question that was later to seize the imagination of the whole country: “Who will be buried under the marble floor of Bedford Abbey on the twenty-first of June– the white countess or the black laundress?”

There were photographs of Reynolds, standing near the long tables, pointing at the bones of both ladies. He was quoted as saying: “You’ve moved them around so many times I can’t tell which is which –nobody could tell–”

When Governor Bedford read the Boston Record, he promptly called Whiffle and Peabody on the telephone and cursed them with such violence that Young Whiffle and Old Peabody grew visibly older and grayer as they listened to him. Shortly after the Governor’s call, Stuart Reynolds came to offer an explanation to Whiffle and Peabody. Old Peabody turned his back and refused to speak to, or look at, Reynolds. Young Whiffle did the talking. His eyes were so icy cold, his face so frozen, that he seemed to emit a freezing vapor as he spoke.

Toward the end of his speech, Young Whiffle was breathing hard. “The house,” he said, “the honor of this house, years of working, of building a reputation, all destroyed. We’re ruined, ruined–” he choked on the word. “Ah,” he said, waving his hands, “Get out, get out, get out, before I kill you–”

The next day the Associated Press picked up the story of this dreadful mix-up and wired it throughout the country. It was a particularly dull period for news, between wars so to speak, and every paper in the United States carried the story on its front page.

In three days’ time Louella Brown and Elizabeth, Countess of Castro, were as famous as movie stars. Crowds gathered out side the mansion in which Governor Bedford lived; still larger and noisier crowds milled in the street in front of the offices of Whiffle and Peabody.

As the twenty-first of Jnne approached, people in New York and London and Paris and Moscow–asked each other the same question: Who would be buried in Bedford Abbey, the countess or the laundress?

Meanwhile Young Whiffle and Old Peabody talked, despera tely seeking something, anything, to save the reputation of Boston’s oldest and most expensive undertaking establishment. Their talk went around and around in circles.

“Nobody knows which set of bones belongs to Louella and which to the countess. Why do you keep saying that it’s Louella Brown who will be buried in the Abbey?” snapped Old Peabody.

“Because the public likes the idea,” Young Whiffle snapped back. “A hundred years from now they’ll say it’s the black laundress who lies in the crypt at Bedford Abbey. And that we put her there. We’re ruined–ruined–ruined–” he muttered. “A black washerwoman!” he said, wringing his hands. “If only she had been white–”

“She might have been Irish,” said Old Peabody coldly. He was annoyed to find how very clearly he could see Louella. With each passing day her presence became sharper, more strongly felt. “And a Catholic. That would have been equally as bad. No, it would have been worse. Because the Catholics would have insisted on a mass, in Bedford Abbey, of all places!

Or she might have been a foreigner –a–a–Russian. Or, God forbid, a Jew!”

“Nonsense,” said Young Whiffle pettishly. “A black washer woman is infinitely worse than anything you’ve mentioned. People are saying it’s some kind of trick, that we’re proving there’s no difference between the races. Oh, we’re ruined–ruined–ruined–” Young Whiffle moaned.

As a last resort, Old Peabody and Young Whiffle went to see Stuart Reynolds. They found him in the shabby rooming house where he lived.

“You did this to us,” Old Peabody said to Reynolds. “Now you figure out a way, an acceptable way, to determine which of those women is which or I’ll–”‘Wewill wait while you think,” said Young Whiffle, looking out of the window.

“I have thought,” Reynolds said wildly. “I’ve thought until I’m nearly crazy.”

“Think some more,” snapped Old Peabody, glaring.

Peabody and Whiffle seated themselves on opposite sides of the small room. Young Whiffle glared out of the window and Old Peabody glared at Reynolds. And Reynolds couldn’t de cide which was worse.

“You knew her, knew Louella, I mean,” said Reynolds. “Can’t you just say, this one’s Louella Brown, pick either one, because, the body, I mean, Whiffle and Peabody, they, she was embalmed there.”

“Don’t be a fooll” said Young Whiffle, his eyes on the win dowsill, glaring at the windowsill, annihilating the windowsill. ‘Whiffle and Peabody would be ruined by such a statement, more ruined than they are at present.”

“How?” demanded Reynolds. Ordinarily he wouldn’t have argued but being shut up in the room with this pair of bony flngered old men had turned him desperate.”Why? After all, who could dispute it? You could get the embalmer, Mr. Luda stone, to say he remembered the neck bone, or the position of the foot–” His voice grew louder. “If you identify the black woman first, nobody’ll question it–”

“Lower your voice,” said Old Peabody.

Young Whiffle stood up and pounded on the dusty window sill. “Because black people, bodies, I mean the black dead–, He took a deep breath. Old Peabody said, “Now relax, Mr. Whiffle, relax. Remember your blood pressure.”

“There’s such a thing as a color line,” shrieked Young Whiffle. “You braying idiot, you, we’re not supposed to handle colored bodies, the colored dead, I mean the dead colored people, in our establishment. We’d never live down a statement like that. We’re fortunate that so far no one has asked how the corpse of Louella Brown, a colored laundress, got on the premises in 1902. Louella was a special case but they’d say that we–”

“But she’s already there!” Reynolds shouted. “You’ve got a colored body or bones, I mean, there now. She was embalmed there. She was buried in Yew Tree Cemetery. Nobody’s said anything about it.”

Old Peabody held up his hand for silence. “Wait,” he said. “There is a bare chance–” He thought for a moment. He found that his thinking was quite confused, he felt he ought to object to Reynolds’ suggestion but he didn’t know why. Vivid images of Louella Brown, wearing a dark dress with white col lars and cuffs, added to his confusion.

Finally he said, ‘We’ll do it, Mr. Whiffle. It’s the only way. And we’ll explain it with dignity. Speak of Louella’s long service, true she did laundry for others, too, but we won’t mention that, talk about her cheerfulness and devotion, emphasize the devotion, burying her in Yew Tree Cemetery was a kind of re ward for service, payment of a debt of gratitude, remember that phrase, ‘debt of gratitude.’ And call in–”he swallowed hard, “the press. Especially that animal from the Boston Record, who wrote the story up the first time. We might serve some of the old brandy and cigars. Then Mr. Ludastone can make his statement. About the position of the foot, he remem bers it–” He paused and glared at Reynolds.”And as for youl You needn’t think we’ll ever permit you inside our doors again, dead or alive.”

Gray-haired, gray-skinned Clarence Ludastone, head em balmer for Whiffle and Peabody, dutifully identified one set of bones as being those of the late Louella Brown. Thus the identity of the countess was firmly established. Half the newspapermen in the country were present at the time. They partook generously of Old Peabody’s best brandy and enthusiastically smoked his finest cigars. The last individual to leave was the weary gentleman who represented the Boston Record.

He leaned against the doorway as he spoke to Old Peabody. “Wonderful yarn,” he said. “Never heard a better one. Congratulations–” And he drifted down the hall.

Because of all the stories about Louella Brown and the Countess of Castro, most of the residents of Boston turned out to watch the funeral cortege of the Bedfords on the twenty-first of June. The ceremony that took place at Bedford Abbey was broadcast over a national hook-up, and the news services wired it around the world, complete with pictures.

Young Whiffle and Old Peabody agreed that the publicity accorded the occasion was disgraceful. But their satisfaction over the successful ending of what had been an extremely embarrassing situation was immense. They had great difficulty preserving the solemn mien required of them during the funeral service.

Young Whiffle and, Old Peabody both suffered slight heart attacks when they saw the next morning’s edition of the Boston Record. For there on the front page was a photograph of Mr. Ludastone, and over it in bold, black type were the words “child embalmer.” The article which accompanied the picture, said, in part:

Who is buried in the crypt at Bedford Abbey? The countess, or Louella the laundress? We ask because Mr. Clarence Ludastone, the suave gentleman who is head embalmer for Whiffle and Pea body, could not possibly identify the bones of Louella Brown, de spite his look of great age. Mr. Ludastone, according to his birth certificate ( which is reproduced on this page) was only two years old at the time of Louella’s death. This reporter has questioned many of Boston’s oldest residents but he has, as yet, been unable to locate anyone who remembers a time when Whiffie and Pea body employed a two-year-old child as embalmer . . .

Eighty-year-old Governor Bedford very nearly had apoplexy when he saw the Boston Record. He hastily called a press con ference. He said that he would personally, publicly ( in front of the press), identify the countess, if it was the countess. He remembered her well, for he had been only thirty-five when she died. He would know instantly if it were she.

Two days later the Governor stalked down the center aisle of that marble gem–Bedford Abbey. He was followed by a veritable hive of newsmen and photographers. Old Peabody and Young WhifBe were waiting for them just inside the crypt. The Governor peered at the interior of the opened casket and drew back. He forgot the eagereared newsmen, who surrounded him, pressed against him. When he spoke he reverted to the simple speech of his early ancestors.

“Why they be nothing but bones here!” he said. “Nothing but bones! Nobody could tell who this be.”

He turned his head, unable to take a second look. He, too, someday, not too far off, how did a man buy immortality, he didn’t want to die, bones rattling inside a casket –ah, no! He reached for his pocket handkerchief, and Young Whiffle thrust a freshly laundered one into his hand.

Governor Bedford wiped his face, his forehead. But not me, he thought. I’m alive. I can’t die. It won’t happen to me. And inside his head a voice kept saying over and over, like the tick ing of a clock: It will. It can. It will. It can. It will.

“You were saying, Governor,” prompted the tall thin news man from the Boston Record.

“I don’t know!” Governor Bedford shouted angrily. “I don’t know! Nobody could tell which be the black laundress and which the white countess from looking at their bones.”

“Governor, Governor,” protested Old Peabody. “Governor, ah–calm yourself, great strain–” And leaning forward, he hissed in the Governor’s reddening ear, “Remember the press, don’t say that, don’t make a statement, don’t commit your self–”

“Stop spitting in my earl” roared the Governor. “Get away! And take your blasted handkerchief with you.” He thrust Young Whiffle’s handkerchief inside Old Peabody’s coat, up near the shoulder. “It stinks, it stinks of death.” Then he strode out of Bedford Abbey, muttering under his breath as he went. The Governor’s statement went around the world, ·in direct quotes. So did the photographs of him, peering inside the cas ket, his mouth open, his eyes staring. There were still other photographs that showed him charging down the center aisle of Bedford Abbey, head down, shoulders thrust forward, even the back of his neck somehow indicative of his fury. Cartoonists showed him, in retreat, words issuing from his shoulder blades, “Nobody could tell who this be–the black laundress or the white countess–”

Sermons were preached about the Governor’s statement, edi torials were written about it, and Congressmen made long winded speeches over the radio. The Mississippi legislature threatened to declare war on the sovereign State of Massachu setts because Governor Bedford’s remarks were an unforgive able insult to believers in white supremacy.

Many radio listeners became completely confused and, be lieving that both ladies were still alive, sent presents to them, sometimes addressed in care of Governor Bedford, and some times addressed in care of Whiffle and Peabody.

Whiffle and Peabody kept the shades drawn in their estab lishment. They scuttled through the streets each morning, hats pulled low over their eyes, en route to their offices. They would have preferred to stay at home ( with the shades drawn) but they agreed it was better to act as though nothing had hap pened. So they spent ten hours a day on the premises as was their custom, though there was absolutely no business.

Young Whiffle paced the floor, hours at a time, wringing his hands, and muttering, “A black washerwoman! We’re ruined–ruined–ruined–I”

Old Peabody found himself wishing that Young Whiffle would not speak of Louella with such contempt. In spite of himself he kept dreaming about her. In the dream, she came quite close to him, a small, brown woman with merry eyes. And after one quick look at him, she put her hands on her hips, threw her head back and laughed and laughed.

He was quite unaccustomed to being laughed at, even in a dream; and the memory of Louella’s laughter lingered with him for hours after he woke up. He could not forget the smallest detail of her appearance: how her shoulders shook as she laughed, and that her teeth were very white and evenly spaced. He thought to avoid this recurrent visitation by sitting up all night, by drinking hot milk, by taking lukewarm baths. Then he tried the exact opposite–he went to bed early, drank cold milk, took scalding hot baths. To no avail. Louella Brown still visited him, each and every night.

Thus it came about that one morning when Young Whiffle began his ritual muttering: “A black washerwoman–we’re ruined– ruined–ruined–” Old Peabody shouted: “Will you stop that caterwauling? One would think the Loch Ness monster lay in the crypt at Bedford Abbey.” He could see Louella Brown standing in front of him, laughing, laughing. And he said, “Louella Brown was a neatly built little woman, a fine woman, full of laughter. I remember her well. She was a gentlewoman. Her bones will do no injury to the Governor’s damned funeral chapel.”

It was a week before Young Whiffle actually heard what Old Peabody was saying, though Peabody made this same outrageous statement, over and over again.

When Young Whiffle finally heard it, there was a quarrel, a violent quarrel, caused by the bones of Louella Brown–that quick–moving, merry little woman.

By the end of the day, the partnership was dissolved, and the ancient and exclusive firm of Whiffle and Peabody, Incorporated, went out of business.

Old Peabody retired; after all, there was no firm he could consider associating with. Young Whiffle retired, too, but he moved all the way to California, and changed his name to Smith, in the hope that no man would ever discover he had once been a member of that blackguardly firm of Whiffle and Peabody, Incorporated.

Despite his retirement, Old Peabody found that Louella Brown still haunted his dreams. What was worse, she took to appearing before him during his waking moments. After a month of this, he went to see Governor Bedford. He had to wait an hour before the Governor came downstairs, walking slowly, leaning on a cane.

Old Peabody wasted no time being courteous. He went straight to the reason for his visit. “I have come,” he said stiffly, “to suggest to you that you put the names of both those women on the marble slab in Bedford Abbey.”

“Never,” said the Governor. “Never, never, never!”

He is afraid to die, Old Peabody thought, eying the Governor. You can always tell by the look on their faces. He shrugged his shoulders. “Every man dies alone, Governor,” he said brutally. “And so it is always best to be at peace with this world and any other world that follows it, when one dies.”

Old Peabody waited a moment. The Governor’s hands were shaking. Fear or palsy, he wondered. Fear, he decided. Fear beyond the question of a doubt.

“Louella Brown visits me every night and frequently during the day,” Peabody said softly. “I am certain that unless you follow my suggestion, she will also visit you.” A muscle in the Governor’s face started to twitch. Peabody said, “When your bones finally lie in the crypt in your marble chapel, I doubt that you want to hear the sound of Louella’s laughter ringing in your ears–till doomsday.”

“Get out!” said the Governor, shuddering. “You’re crazy as a loon.”

“No,” Old Peabody said firmly. “Between us, all of us, we have managed to summon Louella’s spirit.” And he proceeded to tell the Governor how every night, in his dreams, and some times during the day when he was awake, Louella came to stand beside him, and look up at him and laugh. He told it very well, so well in fact that for a moment he thought he saw Lou ella standing in the room, right near Governor Bedford’s left shoulder.

The Governor turned, looked over his shoulder. And then he said, slowly and reluctantly, and with the uneasy feeling that he could already hear Louella’s laughter, “All right.” He paused, took a deep unsteady breath. “What do you suggest I put on the marble slab in the crypt?”

After much discussion, and much writing, and much tearing up of what had been written, they achieved a satisfactory epi taph. If you ever go to Boston and visit Bedford Abbey you will see for yourself how Old Peabody propitiated the bones of the late Louella Brown. For after these words were carved on the marble slab, Louella ceased to haunt Old Peabody:

HERE LIES

ELIZABETH, COUNTESS OF CASTRO

OR

LOUELLA BROWN, GENTLEWOMAN

1830-1902

REBURIED IN BEDFORD ABBEY JUNE 21, 1947

“‘They both wore the breastplate of faith and love; And for a helmet, the hope of salvation.”

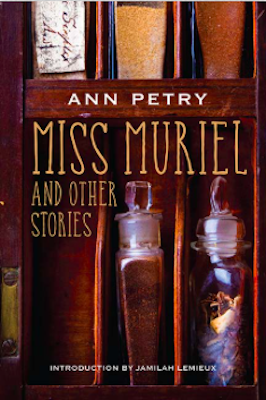

From Miss Muriel and Other Stories. Used with permission of Northwestern University Press. Copyright © 2017 by Ann Petry.