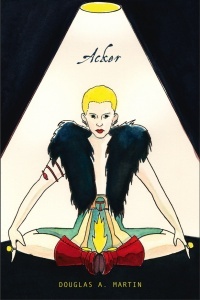

The Births and Deaths of Kathy Acker

How a Literary Icon Remixed Identity Again and Again

It was while I was still living in Athens, Georgia in the 90s and attempting to teach myself how to be a poet that I saw my first books by Kathy Acker, prominently displayed in a place called Stovepipe, a storefront to the side of a coffee house where I worked. I was amused by a reference to Poirot in the beginning pages of The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec by Henri Toulouse Lautrec in the volume Portrait of an Eye, but I understood there was much there beyond that I did not understand. I found it easy too to dismiss the marketing, the mimics of rips to the covers, the pouty face, the words of description like “post-modern” I was not schooled in a way to be impressed by. I sought out what was in the University of Georgia library (Literal Madness, featuring a slew of Shakespeare appropriations and redeployments) and was even more confused.

Some time later, after a particularly rough breakup, I was on my way to the movies with time to kill, hours, and nothing to read. A friend had Blood and Guts in High School in his bag, and I wanted to be closer to him. So I entered the books, and this time, they echoed inside me, resonating with my own inability to make sense of things, to move forward, to let particular feelings go. I read one book and began the next, and the next, continuing on until I had gone through them all, at least once, in a period of about three months. Shortly after I finished her book of essays, Bodies of Work, I heard she was dying and then she did. I had decided I would try to write something, because there was little that I felt was being done in the spirit of her work, little about whom she might have been and whom she had been to me; this was the first time I understood the meaning of losing a writer.

–Douglas A. Martin, November, 2017

__________________________________

A fact I had to frame: I believed she died November 30, 1997, in Tijuana, Mexico. This was after the brief, lucid essay, “The Gift of Disease,” featured in The Guardian, where Kathy Acker also contributed book reviews while living in England. The essay outlined grounds for a courageous, if life-altering decision she made to forego Western medicine and to pursue, as she had for the entirety of a writing career spanning some four decades, alternatives. Her choice is taken up for further debate in those same pages. Jeanette Winterson will come to her defense, stating, “Kathy wanted to be ill in the way she wanted to be well: on her own terms.” Authorized biographer Jason McBride adjusts the date of her death for me to December 1.

Was she someone to let have her say, to follow in the footsteps of, to have as accompaniment through days, someone for me to see an emerging “self” reflected in, someone for me to try to emulate ever? She died not long after someone coming in to the hospital to do her nails had made her quite happy, I learn from a letter in her papers collected at Duke University.

In her own version of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, the narrator, as her Tarot cards—seen as “a psychic map of the present, therefore: the future”—are being read, refers to April 18 as her significator. The birth certificate, driver’s license, and passport of the author give 1947 as birth year, relates Acker’s literary executor, Matias Viegener. Library of Congress information lists 1948, a date her publisher Grove Press takes for a biographical note for a posthumous gathering. In My Mother: Demonology, one of Acker’s last novels published while the author still lived, her narrative strategies have become to redo “childhood,” meaning within the work a set of returned-to memories, dreams, and also the pieces written when younger, the books loved rewritten. Here a narrator, if taken for a stand-in, changes her point of origin again, to something close but that does not exactly square, “I was born on October 6, 1945.”

In a text speculated to originate from 1972, titled The Burning Bombing of America: The Destruction of the U.S., Kathy (Alexander) Acker/(Karen Lehmann), as she signs a letter to her purported father, writes, “I lie on the grass a stake through my heart I am every woman.” Early work, here she formulates, among other ideas, the betrayal of friends, revolution, total chaos, and a “communistic” (perhaps more technically/historically socialist) embrace. The speaker asks: what is communism about? the desire of the heart for more than one love. She asks: how does one (we) recover? I change identity. I see in her, forever spinning out of new configurations, a one-woman identity factory, movements through time and place, days and ages, exploring what one might have been and may still.

In a telling interview performed with publisher, theorist, friend, and once lover Sylvère Lotringer, Kathy Acker agrees with him, “I act through the novels.” (Their chat opens her Semiotext(e) collection, Hannibal Lecter, My Father.) How old the actor was when she died is up for debate. Writing in The London Review of Books, Gary Indiana put her at 53, fact succinctly and coolly floated as his take on Acker’s work and the development of her career is; “she had the cachet of a fetish object and did her best to look like one.” She wanted the “freedom that poetry enjoys over prose,” worthy goal, but he faults her feeling: “Too often her novels were a barrage of attacks on writerly skills she lacked.”

To date the start of Acker’s career—a “brilliant journey,” as Grove Press puts it in the jacket copy for Portrait of an Eye—as 1973 has her writing in the earliest inception, concerned with narratives of origin. The pieces making up The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula and I Dreamt I Was a Nymphomaniac: Imagining were mail-art booklets before being brought together, a business often rehashed in any Acker career accounting. “Tarantulas” is how she refers to “redoings.” These are individual pieces based out of passages elsewhere. They are sketches, reinterpretations, caricatures even, if you like. In the fifth part of The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, the “I” of that text suddenly become Yeats, and at the same time: “I explore my miserable childhood.” She made knowledge of selves sit down together and left readers to try to reconcile if they must. Inside Acker’s The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula by the Black Tarantula, as with most of Acker’s writing, a number of relations become formulated between (her) “self” and others. In The Burning Bombing of America, she writes “people are not only individual people.” Back in the childlike life, freeze frame, before another life or set of lives is picked up. In the absence of stable characters along some steadily progressing plotted timeline, strategic motifs like the author as and author through spider-like approximates, and how constituting environment contribute to intersections caught, that bled into each other, cat cradling.

The narratives start with our ages, our classes, our races, resources, hopes, what we make and mate, how, nationalities, allegiances, said or not, practiced or not, and Acker begins in her points of departure no different. In Kathy Goes to Haiti (1978):

Kathy is a middle-class, though she has no money, American white girl, twenty-nine years of age, no lovers and no prospects of money, who doesn’t believe in anyone or anything.

Identity is consolidated in this way. Lines are drawn in the desert or sea sand. We may feel boxed in ourselves. Among the many categories that she did not want to have her identity written off as: white woman. You are this one thing, before you are this other, you are told. Identity in Acker is in a tension with the reductive, what is seen, what is said. Another self-and-other dichotomy is pronounced and made to exist as that between the animal and human. (In The Burning Bombing of America, “we no longer want to be human.”) While she wanted her work to be her world, she also situated where one understanding of that came up against another. A body of one mind, as much as any page in any book, was in Acker a modified subject site. Previous existences are there to be journeyed over and through, to her liking, in ongoing attempts to leave behind prior definitions and dominations. These make a complex, imaginative feedback of loops. “I always think that the more I learn, the wider the ocean in front of me becomes,” she says in a letter to Richard Hell, archived with his papers at Fales Library, NYU. I got a feeling how this was not to be avoided, but desired, the opening, expanding, more shifting grounds.

Like that rabbit hole of her own, she tends a psyche of individuals: full of, plenty of, reflections, distortions, ruptures, rerouted potentials. Imagination and desire, as they get sown up by language especially, under almost constant bombardment in advancing reductive and visually saturated culture, are a contestable space where all the dreams may be colonized already in marketing back to us. It is such space, blank and otherwise, in and around (recorded) language Acker wants to open with priors, cut loose, situating queerly sights of mouths, legs, and collapsing almighty already defined mind. I quote Susan Sontag, in particular on the life of Simone Weil, whom Acker calls upon elsewhere in her own way: Perhaps there are certain ages which do not need truth as much as they need a deepening of the sense of reality, a widening of the imagination. How many senses make that reality is one of the stakes for a subject for Acker. Her work positions self and writing in variegated divides between public and private to challenge limiting, preconceived notions of decorum and form, to hope to express from what had been that repressed.

__________________________________

Adapted from Acker by Douglas A. Martin, courtesy Nightboat Books.