For his thirty-sixth birthday, she got cancer.

The planned part was to go to Catalina, and circumstances prevailed—schedules permitted, spots opened up, traffic flowed, boats didn’t sink, everything broke just the right way—so that, their sole night on the island, they found themselves in the darkness past Abalone Point, beyond the lights of Avalon, listening to a Mexican woman talk about her brother’s alien abduction.

“Not even I believe him,” the woman said. She laughed. “He was always that kid who got in trouble. When he was little he had it in for birds. Later it was drugs. Everyone thinks he’s crazy. But he means well,” she said. “No one else ever thinks so, but I do. Troubled people,” she said, “are just a big tumble of confusion. So I’m trying to understand him. That’s why I’m here.”

The three other people on the tour and the tour guide all nodded. The woman was young and elegant, with a sweeping jaw and strong cheekbones, her hair curled behind her ears, and she wore an ornate dress: the collar was woven with small, gleaming beads, and the sleeves were a dark-colored lace, and Kate, one of three, wondered how the woman wasn’t cold, here in the darkness beside the sea. The man who was with the woman—muscled, cheerful, he’d made it clear he was ex-military—put his arm around her. “See,” he said. “That’s why you’re such a great person.”

“My brother says it hurt,” the woman said. “The things they did to him up there.”

“Right,” the man with her said.

“A lot,” the woman said, and she gave a nervous giggle.

The two were a strange pairing in a small and strange group: them and Kate and her husband, Kevin, whom she hadn’t yet told the news. Strangest of all was the tour guide, a local Catalinan whom they all without conferring suspected was half-crocked as she led the tour, talking about the island’s stranger things. The guide now blinked and shook her head. “Lordy,” she said. “I don’t want to be abducted, not ever. That’s some story. Isn’t it?” She looked at Kate and Kevin who obliged with nods. “And these things happen,” the guide said, “and they’re important to share, and here we are,” she said, “caught up in the vastness of the universe. Look out there,” she said, gesturing grandly toward the sea. “Look across those waters. At the distant lights of LA. Sit and listen to this next story,” she said. “Let me tell you about the Battle of Los Angeles.”

They’d never been to Catalina Island, was the thing, even though they’d both spent over ten years living in Los Angeles, much of that time together, the last several married. It wasn’t that Catalina was exceptionally far. An hour-long ferry ride to the island and an hour-long drive from where they lived to the ferry terminal in Long Beach. But the ferry was expensive, hundred bucks a pop, and park- ing was expensive, twenty dollars a day, and if they stayed the night on Catalina, that’d cost too, not to mention paying someone to feed their cat while they were gone—and now that they had a house, a mortgage? For years they’d wondered: was it worth it? All that money just to get to a rock out in the ocean, when really, if you thought about it in the abstract, that was where they already lived.

“But Catalina is great,” their friends assured them. “You have to go. It’s like—like what?” their friends said, uncertain. It was a happy uncertainty though: they squinted skyward, reaching in their minds for all the great things that Catalina was like.

“Like perhaps,” Kevin asked, “the elusive ingredients in a good cocktail?” “Maybe that?” the friends said. “Maybe not? But do the flying fish tour! The golf carts! The bison tour! The happy hours!”

“Add a dash of bitters,” Kevin said, laughing, “and you’ve got one weird drink!” The four of them were at a neighborhood tavern. It was the Thursday before Good Friday, a holiday for them all. The other couple worked as an engineer (the husband) and in finance (the wife), and though the two had better paying and more stable jobs than Kevin and Kate, especially compared to the latter pair’s fixed-term lecturer positions, Kevin and Kate had foregone their grudge about this or had at least shifted it away from their two friends and toward systems and society, and so they’d met, as they did each week, for beers and cocktails. “Tell them,” Kevin said. “Tell them why we’re finally going.”

Everyone faced Kate. She’d been stirring the straw in her water glass. The ice had melted some time before, and though she hadn’t asked for a lemon slice, and though there wasn’t one present, small bits resembling lemon vesicles swirled in the glass. She enjoyed the swirling, creating the vortex, forcing the tiny bits round and round.

Kevin hated birthdays. He’d told her as much their first year living together.

She released the straw and smiled.

“We got,” she admitted, “the two-for-one birthday ferry deal.”

“For the first time,” Kevin said, pleased, “it fell on a day we could actually use it.”

“Good Friday!” the friends said. “What a day for your birthday to fall on!”

“Why?” Kate said. “Do they have Easter celebrations? Is it religious?”

The friends assured her it wasn’t religious, that they just meant it was good because the day was called good. They seemed bemused by her question, which slightly annoyed her, but she held her smile as they described more of their favorite island activities—parasailing, going to the casino (they winked as they said this), visiting the museum. Kate picked up the straw again. She wondered what religious activities were like on Good Friday on a touristy island. Something baptismal, she suspected. Was Good Friday the day that Jesus had died? That didn’t sound good exactly. Though maybe taking him off the cross finally had been good. The doctor had said it was real, a real thing to accept, to address, that they needed to make a game plan. A game plan, she thought. How dull. The little pale bits swirled and swirled within her glass, and she thought that probably was what it was: an actor with bloody hands and feet, the crown of thorns, the whole nine in some sort of beach pageant. A gathered and hushed crowd. Him gazing up at the sun, maybe imploringly, then letting out a last sigh, chin falling to chest. And others in ancient garb lowering him carefully, carrying him to the shore, where they’d clean his wounds.

“You okay?” Kevin said. His voice was soft.

And then, once again, they were all watching her.

“What is it?” the friends asked. “What’s wrong? Is the beer bad?” Kate shrugged. She had honestly forgotten what her beer tasted like.

Kevin reached over and held his hand out, hovering. She nodded, and he took her glass and sipped, and his face soured. “Way too bitter,” he said, “even for an IPA. Want to trade?”

Again, they all looked at her expectantly. Kate sighed and reached with her fingers, reached around deep, deep inside herself, and after a moment she found it—found a pleasant smile, pulled it up, placed it on her lips, and nodded.

Plus, Kevin hated birthdays. He’d told her as much their first year living together. She was getting cash out of his wallet—with his permission, though at the time it still made her slightly antsy; what might one find in another’s wallet?—and she saw his driver’s license. He’d posed for the picture absurdly, eyes bulged so that he looked like a madman, which, he said, was an act of protest at having to get a new license. “Why not be silly,” he said, “in the face of the serious?”

“So yesterday,” she’d said, returning his wallet to the console table, “was your birthday?”

Kevin was in their old apartment’s living room, watching baseball on TV, his back to her. Kate saw him flinch a moment before making himself relax. Then he turned and looked at her. “So I guess,” he said gravely, “I should tell you about me and birthdays.”

Not that it was interesting—the long and short of it being that he hated birthdays, had a hard time feeling happy on birthdays. Kate listened patiently as he described his issues, which he admitted were silly, all in his head, but still, there they were. In college and graduate school, he explained, no one cared about his birthday because no one knew, and though he wanted people to know, he didn’t want to seem like he wanted them to know, so instead he went through the special day alone in a sort of sad knowledge that it was his birthday, this seemingly happy secret stuck inside him, minus pomp, minus fun. He’d gone a stretch of seven birthdays this way: begrudgingly silent. It was true that his mom sent packages—which she still did; the very next day one arrived, which alarmed Kate, especially as it held within it, amongst other gifts, a pair of green boxer shorts. “To wear green for the holiday,” he explained, and Kate had nodded and thought, boxer shorts? From a mom? Even that, he said, the tradition of his mom annually sending packages, only made him feel more alone.

“Opening a present with no one around, it’s but a small tragedy,” Kevin said, waving a hand. “A tragetto. Really, it all started earlier than that,” he said. Kate was sitting on the couch beside him, and though he’d muted the TV, sometimes it still drew his attention, and he’d stop talking a moment, and Kate would sit there waiting for him to go on, waiting impatiently for the story to end. She wondered at how odd he was: that he felt comfortable telling her about a very peculiar problem that existed only in his head yet every few minutes made her wait while he watched the game.

This world, Kate thought, marveling too at herself for not knowing this basic information, not knowing that she didn’t know it, not needing to know. This man is going to be my husband!

“When I was four,” Kevin continued, “my family threw me this huge party. My grandma had gotten a divorce, I think, or she was celebrating sobriety? They invited thirty kids. Thirty! Ice cream cake, a donkey, a clown, everything. And what happens to the birthday boy? Pinkeye happens. I’m locked in my bedroom all day, watching the other kids play through my window. That,” Kevin said, “is the story of my birthday life. It’s also probably why I like donkeys so much.”

Kate laughed, and he glanced at her. “I’m serious,” he said. “I love donkeys. If we ever live in the countryside, I’m getting one. Maybe two. Anyway, probably the only birthday I ever actually liked was in fifth grade, when my mom let me ditch school, took me to the movies—Little Shop of Horrors, which, whatever—and bought me Round Table for lunch, along with a pack of Topps baseball cards, stale gum and all.” He smiled. “I got a Darryl Strawberry that day.”

“He was your favorite player, right?” Kate said.

Kevin shrugged. “At least then,” he said. “Not anymore. Not for a long time.

Shit,” he said, facing the television.

Then he looked back at her. “That,” he said, “was the best birthday. The only good one.”

And at that moment, Kate, feeling heroic, decided she would fix the problem.

__________________________________

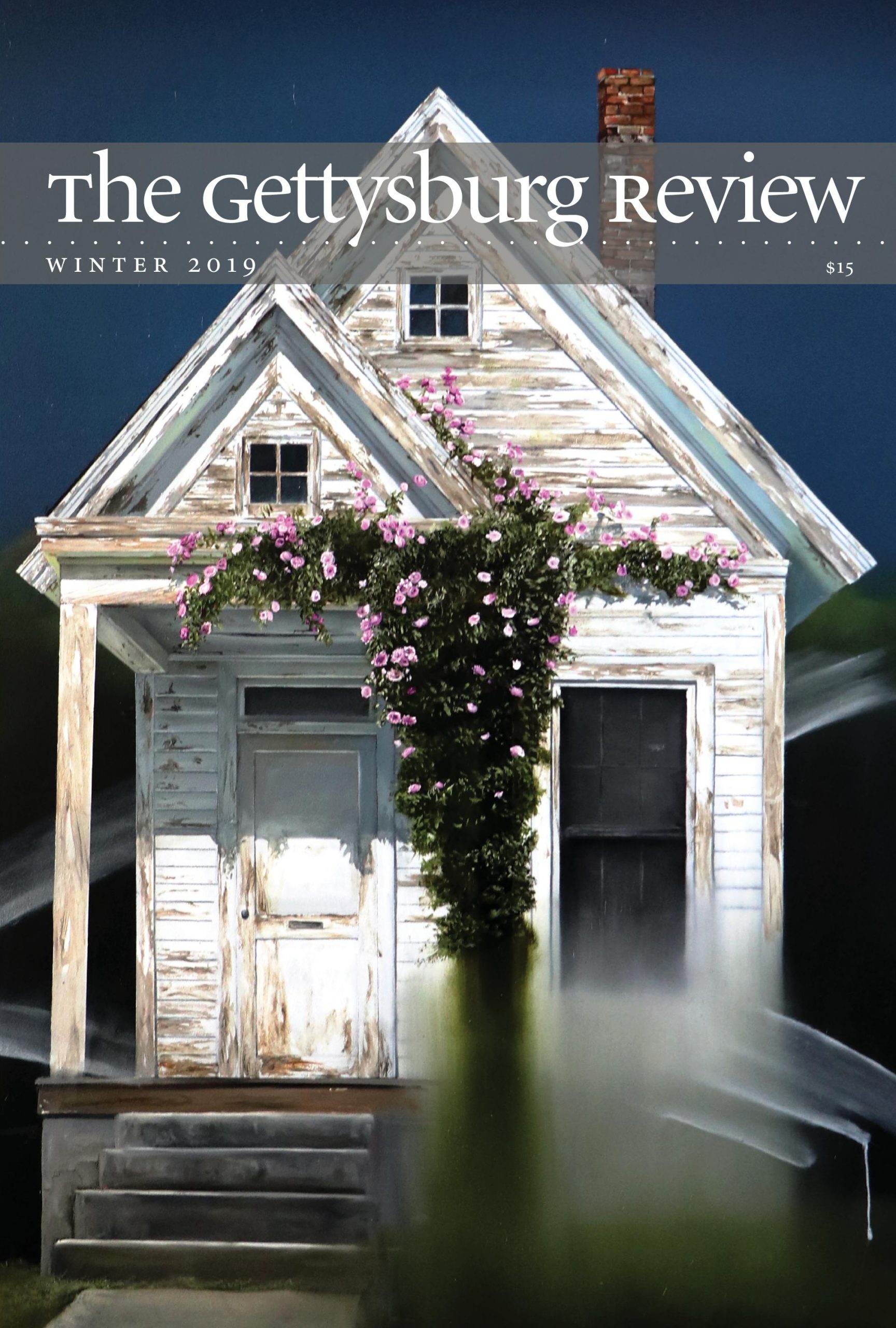

From “The Battle of Los Angeles” by Sean Bernard, featured in Gettysburg Review, Vol. 32, No. 4.