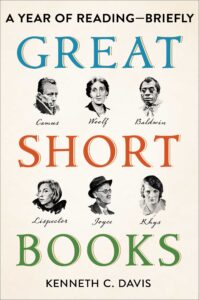

The Antidote to Everything: Kenneth C. Davis on the Balm of Short Novels

“A short novel is like a great first date.”

Time. We all wish we had more of it. To do errands. To hit the gym or take a long walk. To bake bread or whip up that recipe we clipped last year. And, maybe, to simply read. The intrusion of the screen—first the big ones in our living rooms, then those sitting on our desks, and finally, the little ones many of us carry around— has made it more challenging to make space for the simple joy of getting lost in a book.

“In our society, where it is hard to find time to do anything properly, even once, the leisure—which is part of the pleasure—of reading is one of our culture-casualties,” writes novelist Jeanette Winterson. “For us, books have turned into fast food, to be consumed in the gaps between one bout of relentless living and the next.”

And then a pandemic made it even more challenging. For many of us, reading anything besides the deluge of news—catastrophically bad, between Covid-19 and the toxic political atmosphere—became increasingly difficult, particularly for those who felt compelled to “doom scroll.”

The pandemic changed the way we all think, feel, and behave. Sleep became harder. Our normal patterns of working and socializing were demolished by “languishing,” a term coined by sociologist Corey Keyes, and what psychologist Adam Grant called “Zoom fatigue.” We all stressed about finances, jobs, our children’s education, and the basic right to pursue happiness. These demands hit hard at our attention spans, which meant less time and motivation for reading, even though many experts advised this was the right prescription for what ailed us.

During an earlier plague, the Italian writer Boccaccio understood this basic truth: short is beautiful.During the first months of the Covid outbreak in early 2020, and then as a bitterly contested presidential election tested the very soul of American democracy, I rediscovered the balm of reading fiction. Not as an escape from the constant press of dreadful news, but as an antidote. Fiction can provide insight, instruction, and inspiration, even as it takes our minds from the anxiety of the moment.

An expansive universe, fiction includes mystery, historical fiction, science fiction, fantasy, thriller, romance. For those who seek a complete education, reading fiction occupies a central pillar of our “Cultural Literacy.” For many people, that still means commencing with the classics, the so-called Great Books or Western Canon. You know those literary heavyweights we were all supposed to read and even reread: Anna Karenina, Bleak House, Pride and Prejudice, Middlemarch, and Moby-Dick. Not to mention all seven volumes of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

Of course, some of those literary sacred cows have been supplanted by a new generation of modern classics, an alternative canon that is more inclusive of overlooked women writers as well as people of color and gay writers.

But let’s get real. Even when we’re not in lockdown mode, many of us simply lack the energy, inclination, or patience to get through some of those illustrious but weighty tomes, in spite of our very best intentions. Whether you were inclined to read the old or new classics, I am reminded of Mark Twain’s definition of “classic”: “A book which people praise and don’t read.”

Then I found a simple solution: short novels.

During an earlier plague, the Italian writer Boccaccio understood this basic truth: short is beautiful. As the Black Death struck Florence in 1348, Boccaccio began writing a series of stories he completed in 1353. Boccaccio’s Decameron is a collection of one hundred brief tales, each called a novella. In this masterpiece, ten characters—seven women and three men—each tell a story every day for ten days as they seek refuge from the plague in a villa near Florence. A combination of parables, adventures, and love stories, some quite bawdy and many skewering the Church and the priesthood, Boccaccio’s work was composed in the vernacular Italian. It remains a foundational text in Western literature.

A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more.Early in the pandemic, I began reading one tale a day from the Decameron. And I realized that Boccaccio was on to something. There is a liberating quality about brief tales told in the midst of a pandemic. From Boccaccio, I moved on to short novels.

At first, my reading was dictated by the books on my shelves, as the library and bookstores were also in lockdown and the very valuable and pleasurable act of browsing was out of the question. When my local branch of the New York Public Library reopened, it was one of the most liberating moments in the pandemic. I read as the books I had requested became available for “grab and go.” Praise the library! I soon had a stack of thirty books—the library’s max checkouts allowed. Then my local bookstore, Three Lives & Company, reopened for five customers at a time—another moment of jubilee.

Based on my reading experience over a year in lockdown, and considerable research, I curated a guide to some of the greatest short fiction from around the world and published in English, including a broad diversity of writers and voices. As I define them, short novels encompass fiction of one hundred to two hundred pages.

Why short books?

A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more. It can lead to greater possibilities. But there is no long-term commitment.

Short novels can often be read in one to several sittings. With careful rationing, they can be easily enjoyed at the rate of one book per week.

*

Short novels are literature’s equivalent to the stand-up comedian Rodney Dangerfield’s signature line: they “get no respect.”

Certainly, when set against short stories they do not. Esteemed magazines such as the New Yorker continue an honored tradition of publishing short stories, which are often the writer’s stepping-stone to producing longer work. And many novelists have published prizewinning story collections, including Ernest Hemingway, Katherine Anne Porter, and others. At the other extreme are those long novels and multivolume sagas that attract the attention of critics, reviewers, and many readers.

Short novels, on the other hand, have been shortchanged. They occupy the place of the neglected middle child of the literary world. It is as if length determines merit. Short-listed—no pun intended— for the prestigious Man Booker Prize in 2007, Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach provoked controversy because it was deemed too short—sniffed at as a mere novella. So, a degree of critical prejudice—call it literary sizeism—exists against short fiction.

Short can be masterful. Short can be rewarding. Evidence of that fact is the inclusion of several Pulitzer-winning books and eleven Nobel Prize winners in my collection Great Short Books. The short work of such Nobel laureates as Thomas Mann, Ernest Hemingway, Nadine Gordimer, Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, and Kazuo Ishiguro offers ample evidence of why these literary virtuosos won their accolades.

Short novels, on the other hand, have been shortchanged. They occupy the place of the neglected middle child of the literary world. It is as if length determines merit.When the pandemic’s intrusion meant a shift to remote learning, I must confess I dropped out of an Italian class I was taking. Without classes to attend and missing the personal connections with professors and fellow students, my daily reading became even more important.

I do not consider myself a literary scholar or a book critic. I view myself as what Virginia Woolf once described as “the Common Reader” who “differs from the critic and scholar.”

“He is worse educated, and nature has not gifted him so generously,” wrote Woolf. “He reads for his own pleasure rather than to impart knowledge or correct the opinions of others. Above all, he is guided by the instinct to create for himself, out of whatever odds and ends he can come by, some kind of whole—a portrait of a man, a sketch of an age, a theory of the art of writing.”

For most of my life, I have been that “Common Reader.” I suspect that a great many people would place themselves in that category. Whatever genre or style they might prefer, they read for their “own pleasure,” as Woolf put it. I take exception to the notion that any reading constitutes a “guilty pleasure.”

It is more important than ever to foster reading. As a small boy forbidden to learn his ABCs, the great American abolitionist Frederick Douglass understood why enslaved people were not permitted to learn to read. It was one way the white man kept the Black man in chains. There is a reason that dictators order the burning of books and seek to silence writers, from Voltaire to Solzhenitsyn and in our own time. Reading fiction can provide “that glimpse of truth for which . . . [we] have forgotten to ask,” as Joseph Conrad once wrote. Reading is fundamental, not only to the development of our hearts, minds, and spirits but also to Democracy with a capital D. My goal is always to start a good conversation—about books.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—Briefly by Kenneth C. Davis. Excerpted with the permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2022 by Kenneth C. Davis.