The Annotated Nightstand: What Hannah Matthews is Reading Now and Next

Margaret Renkl, Ye Chun, Sabia C. Wade, and More.

Since the overturning of Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Court in 2022, many of us are met with an overwhelming variety of media and news regarding what a “post-Roe” America looks like. The statistics, it seems, give us a far more grim outlook than even “pre-Roe” America, with federal judges interceding in FDA approved pharmaceuticals, and state laws requiring people bring their pregnancies to term even in the case of rape, the nonviability of the fetus, and/or the dangers to themselves in the process.

Perhaps now more than in living memory, people—including this one—are learning more about the multitudinous shapes pregnancy can take, and the equally manifold reasons why a pregnancy may need to end (or, embracing the less-loaded concept, a period cycle simply brought back).

Doulas are normally associated with childbirth—the rite of passage for parent and baby alike, with the doula as a support aside from those in the medical establishment. Hannah Matthews’ You or Someone You Love subverts the common ideas of the doula with its subtitle: “Reflections from an Abortion Doula.” Beginning with her own experiences with abortion, Matthews considers the different approaches to reproductive justice in such a way to illustrate the dimensions of a topic flattened again and again by the deluge of daily news.

Perhaps most important, as Kirkus Review states, “Matthews strives to center the knowledge and narratives of Black and brown practitioners because they not only bear the brunt of reproductive violence; they also come up with some of the most creative solutions to patriarchy-induced problems.” She gives us a sense of how nonprofits, activists, witches, religious leaders, herbalists, doctors, and the book’s readers themselves can care for those who need an abortion (physically, emotionally). This in a political and legal landscape that invokes an increasing feeling that these people’s options are becoming a foregone conclusion.

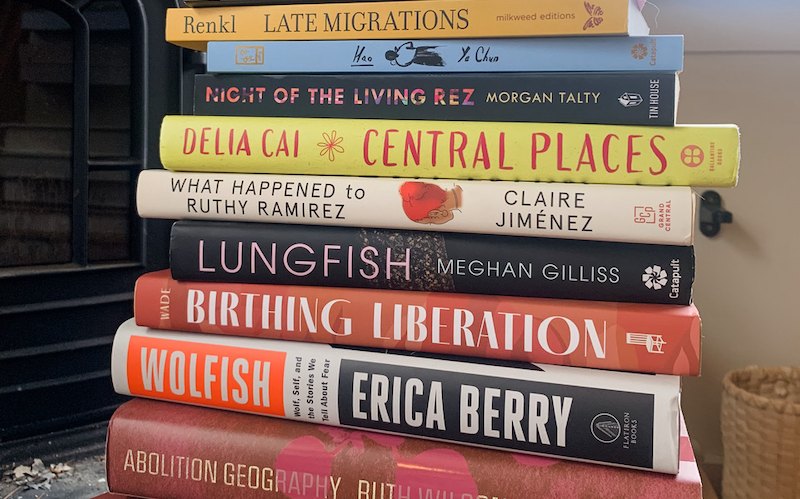

Regarding her to-read pile, Matthews tells us, “My TBR stack doesn’t even fit on my nightstand–both because it’s so unwieldy and because that precious little square of real estate is piled high with my toddler’s board books and sippy cups. A couple of these books I am re-reading (or keeping close in order to return to well-loved sections or sentences, mostly to share with friends I think might find them beautiful and/or useful in a given moment), but most are brand-new to me, and keeping me company through this unsettling and sleep-deprived spring.”

Eds. Rebecca Solnit and Thelma Young Lutunatabua, Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility

Solnit and Young Lutunatabua both spoke to Vogue about this collection in ways that capture its ethos. Young Lutunatabua states, “Hope is not the guarantee that things will be okay. It’s the recognition that there’s spaciousness for action, that the future is uncertain, and in that uncertainty, we have space to step into and make the future we want.” Solnit explains, “People think if you don’t win everything, you lose everything. They think it’s too late. They think nobody cares, that nobody’s doing anything…We feel really strongly that people need good facts about the realities of climate change and what we can do about it.”

Ella Baxter, New Animal

The protagonist in Baxter’s New Animal is in a holding pattern as a relatively isolated cosmetic mortician in the family business. She ends up in Tasmania with her birth father and also, separately, exploring a BDSM club there. The precipitating event is her loving mother’s sudden death that leaves the twenty-something unmoored with only a stepfather and older brother as her community. Clocking in at 3.42 on Goodreads, Baxter’s novel is illustrating Ruth Madievsky’s assertion in her LitHub essay that “excellent (and often critically-acclaimed) women-centric literary fiction tends to fall into the gulf between 3.2 and 3.8 stars” on the site.

Jaime Green, The Possibility of Life: Science, Imagination, and Our Quest for Kinship in the Cosmos

A consideration of humans’ hope to find life on other planets, with everything from history and science fiction, Leslie Jamison says Green’s book “The Possibility of Life takes the reader on an utterly gripping, endlessly surprising voyage from the ‘hopeful monsters’ of early multicellular organisms to the records of human existence hurtling beyond the edge of our solar system. Green’s voice is rigorous, curious, tender, and often rightfully bemused. She is the best company I could imagine for this journey to the limits of what we can imagine, and a thrilling ruminator on what these acts of imagination might teach us about ourselves.”

Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss

Renkl has written opinion pieces for the New York Times for some time, attending to issues such as climate change and gun laws in the South. I’m really connecting with her essay “The Beautiful and Terrifying Arrival of an Early Spring,” as it feels nearly like summer as I write this. An upper-80s mid-April day on the East Coast sent every heat-stunned cranking up their air conditioners—and now my neighborhood has a blackout. “I worry that this early spring is the harbinger of a brutal and everlasting summer,” she writes. “For the life of me, I cannot understand the politicians who keep behaving as though what is happening to the climate isn’t an existential threat. But I also can’t help delighting in these tiny flowers reaching for the sun, and I make no effort to beat back my pleasure.”

Ye Chun, Hao

In his review at NPR, Michael Schaub explains that “hao” means “fine or OK, an assurance that nothing’s awry, that everything’s going to be all right. In Ye Chun’s stunning new short story collection Hao, though, the characters are anything but OK.” Schaub goes on to describe the titular story as one “brimming with anger, but Ye relates it with a surgical clarity that effectively brings the enormities of the Cultural Revolution into focus. It’s a stunning look at despair in the face of unspeakable evil, chilling and perfectly written. ‘But what is hao in this world, where good books are burned, good people condemned, meanness considered a good trait, violence good conduct?’” one character says. “People say hao when their eyes are marred with suspicion and dread. They say hao when they are tattered inside.”

Morgan Talty, Night of the Living Rez

Morgan Talty recently won the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize as well as the NBCC Award for this dynamite debut short story collection. In an interview here on Lit Hub, he says, “I see the short story has something drawing power from what’s not on the page, whereas the novel gets its strength from the sheer length of it. They each have their own specificity, and they each have to have the principles of fiction—characterization, setting, point of view, and so on.

But to me, my experience writing in either form is pretty similar since my mission is to tell a story that, when the reader is done, feels like it had happened to them. Each story—regardless of genre—requires its own set of rules, its own logic, and part of my job is finding that logic and listening to it so I can see the story to the end.”

Delia Cai, Central Places

So many of us leave home in hopes to strike out new lives apart from family, expectations, and become who we want to be on our own terms. Cai’s protagonist Audrey has done just that, leaving the Midwest for New York City. Beyond this, she’s managed to accrue the trappings of the NYC lifestyle many yearn for: a job that pays, a “perfect” fiancé. If there weren’t hijinks, it wouldn’t be much of a novel, though.

Audrey’s fiancé is white, and she’s the daughter of Chinese immigrant parents. She wants to introduce him to her family before they get married. She has an old crush who still hangs around her hometown. Jean Chen Ho says of Cai’s novel, “A moving, nuanced novel about race, class, and the unspoken power dynamics of an interracial relationship, Central Places negotiates the personal and the political with unsparing precision.”

Claire Jiménez, What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez

“A Staten Island Puerto Rican family reckons with the disappearance of a 13-year-old girl in Jiménez’s brilliant debut. In 1996, middle daughter Ruthy Ramirez, a defiant, wildly independent eighth grader, mysteriously vanishes after track practice,” states Publishers Weekly in its starred review. A dozen years after her disappearance, Ruthy’s mother and two sisters are in a holding pattern. Until one sister sees who she thinks may be Ruthy on a reality show called Catfight, the content of which you can likely guess. The review goes on: “The author perfectly harnesses the Ramirez women’s alternating viewpoints to illuminate how the years have worn on them, and in the stunning ending, she cannily reveal the truth behind Ruthy’s disappearance. This is a knockout.”

Meghan Gilliss, Lungfish

A woman, Tuck, her toddler, and opioid-addicted husband squat in an abandoned family home in an island off of Maine with essentially no income in Gilliss’ debut novel. Marcy Dermansky writes in the New York Times, “Gilliss’s language is an elemental force. A foraged mushroom is not just a mushroom; it is a potential threat. ‘I spread the mushrooms on the table beneath the hanging bulb, bright caps down, ridged undersides up… I look at them. You are chanterelles, right? I say.’

It makes sense that Tuck is talking to these possibly poisonous mushrooms, living on a deserted island in the company of only an ailing husband and a toddler. Her dialogue with both animate and inanimate companions is offered without quotation marks. The prose exhibits as little structure as Tuck’s life. Gilliss’s short, artfully titled chapters (‘So,’ ‘Catch,’ ‘Familiar,’) sometimes slip effortlessly into something like poetry.”

Sabia C. Wade, Birthing Liberation: How Reproductive Justice Can Set Us Free

The jacket copy for this vital book states, “Sabia C. Wade, renowned radical doula and educator, speaks to the intersections of systemic issues—such as access to health care, house transportation, and nutrition—and personal trauma work that, if healed, have the power to lead us to collective liberation in all facets of life. Collective liberation rests on the idea that in order for us all to have equity in this world—from the safety of childbirth, to the ability to bring a baby home to a safe community, to having access to resources, safety, and opportunities over the long term—we must all become liberated individuals.”

Erica Berry, Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear

In a review in the Atlantic, Lily Meyer writes, “In classic fables and fairy tales, no predator—and perhaps no villain—makes more frequent appearances than the wolf. Greek antiquity gives us the Boy Who Cried Wolf, Little Red Riding Hood famously gets eaten by a wolf, and yet another one blows down the Three Little Pigs’ houses. Wolfish, the writer Erica Berry’s debut, looks both at these invented wolves and at the real ones that have, of late, returned to her home state of Oregon; she also examines the more contemporary wolf metaphors—lone-wolf terrorists, warriors as wolves—that many people use to describe, or perhaps justify, their fear of other humans.”

But also, I am in love this cover. It’s direct, sleek, yet gains more dimension the more you look at it. Berry explained to Lit Hub about the its design, “I struggled to imagine the cover for this book…It wasn’t until one of my best friends from childhood found an antique French print of a wolf shadow puppet that I felt something click. It was exactly what I wanted the book to do: to map the shadows on the wall, but also the hands that made it.”

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography

I love that Gilmore did an interview in Teen Vogue, and hopefully shared her insights with many teens throughout the country because of it. She states, “what I keep learning over and over again, and I try to say in Abolition Geography in about 100 different places: Go into something that already exists, and do that work towards the end of helping to tip it away from reinforcing the system towards weakening the system. That’s infiltrating. Or innovate. If something doesn’t exist, make it. [Abolitionist] Mariame Kaba: She makes things every day. But she doesn’t make it sitting alone in her apartment. It’s all social. It’s all collectively done.”

______________________

Hannah Matthews’ You or Someone You Love: Reflections from an Abortion Doula is available now from Atria Books.