The Annotated Nightstand: What Chris Belcher is Reading Now and Next

A New (at Lit Hub) Series by Diana Arterian

Chris Belcher’s memoir Pretty Baby (out this week from Simon & Schuster) lays out a life not so much complicated by identity than the ways society responds to what it has decided is deviant. From Belcher’s queerness in her small hometown in West Virginia to her work as a domme while earning her PhD, she is faced time and again with the forces of cultural hegemony that try to pin her down, force her into submission.

Belcher won beauty pageants as a baby, was a high school cheerleader. She also realized quickly that heterosexual sex often left women (or at the very least herself) feeling disempowered. The glory of the book, beyond Belcher’s sharp mind and tight lines, is the ways in which Belcher finds egress from social and financial constriction through her sexuality and sex work. The ways in which the two worlds that, on paper, seem disparate—academia and the sex dungeon—are defined by notions of power is something Belcher explores with acumen.

The dichotomy between the two isn’t simple or obvious (the sex work doesn’t always put Belcher in the position of the empowered, the academy is rarely open-minded). “Everyone wants whores to stop whoring,” she writes, “but when they do, they can’t get hired at Starbucks.” Beyond all this, Belcher is able to infuse a book regarding sexuality, gender, class with a humor that is rare and, thus, something to treasure.

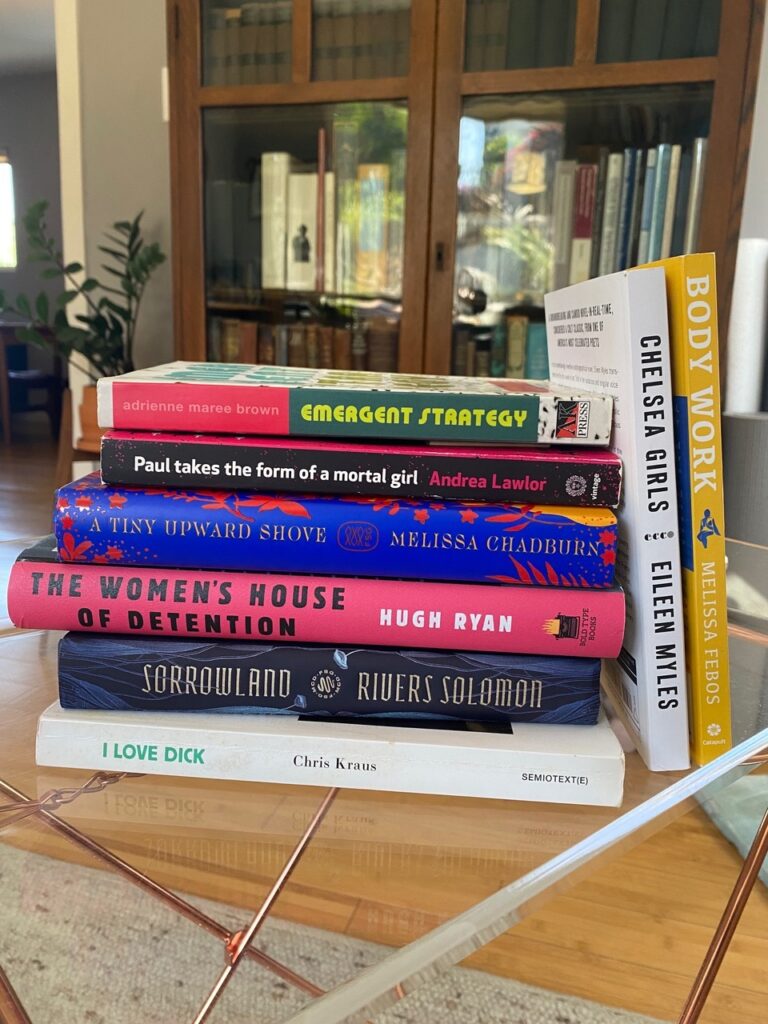

On her to-read pile, Belcher writes, “On the verge of publishing and promoting a book that places sexuality front and center, I’m revisiting some of the titles that informed my approach to writing about sex and bodies, pleasure and disgust, and a few I wish I had read before even endeavoring to write it.

This summer, I’m also making space for the books that will end up on my syllabi come fall semester—the political and pedagogical guidance that will help me put those syllabi together—and a few novels I simply plan to read on the beach. They may not be classified as beach-reads, but I’ve been known to vibe clash; I was a twelve-year-old who enjoyed reading passages from Go Ask Alice aloud at slumber parties.”

adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds

Octavia Butler writes, “When apparent stability disintegrates. / As it must— / God is Change—” Pursuing Octavia Butler’s ideas about change as a site of wisdom and means for growth, brown has written a book to aid her readers in a world that seems increasingly destabilized by changes that create dread and terror. brown co-edited the vital collection Octavia’s Brood, and this book feels no less important. The jacket copy states, “Rather than steel ourselves against such change, this book invites us to feel, map, assess, and learn from the swirling patterns around us in order to better understand and influence them as they happen.”

Andrea Lawlor, Paul Takes on the Form of a Mortal Girl

This novel, set in the 1990s, follows the protagonist Paul, who is a bartender at the only gay club in town. Paul is able to quickly shift into Polly, operating as a man or woman depending on his desire and what he thinks will rouse interest in a sexual partner (his pronouns remain he/him throughout, despite this change). Probably the best endorsement comes from the New York Times review, which states that the book is “Difficult to quote in a family newspaper.” I’m convinced.

Melissa Chadburn, Tiny Upward Shove

Melissa was the first guest on this series. This is what I had to say about her remarkable novel there: “Since reading ‘The Throwaways’ at The Rumpus, I have been grabby for more of voice and its self-assured, quick clip. The details she brings to the fore never cease to surprise. Her remarkable wealth of knowledge, both personal and journalistic, regarding the foster system in the United States has vitally informed her writing. Her new novel, A Tiny Upward Shove, is out from Farrar, Straus and Giroux today. In it, a young Filipina woman’s body is entered by an aswang spirit, which helps recount her life of instability, assault, foster care, early emancipation, and the difficulty beyond.”

Hugh Ryan, The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison

This book describes the history of the House of D, the Greenwich Village women’s prison known for its cruelties the staff inflicted on those incarcerated within its walls. In an interview with NPR, Ryan explains, “For men, the prisons try to make you a good citizen. But for women, the prison tries to make you a good woman — and that’s a very different thing. And that is the reason why so many gender-nonconforming people, why so many queer women, lesbian women, butches, studs, trans men get caught up in the prison system, because for those people who are concerned about the lives of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, queerness was seen as a threat to ever being a normal, healthy, happy, productive member of society.”

Rivers Solomon, Sorrowland

This novel is called a “genre-bending Gothic,” which centers around the protagonist Vern – a Black teenager who has escaped from a Christian cult run and populated by Black members in order to escape the oppression of white supremacy in “Cainland.” Unfortunately, Cainland’s strictures are oppressive in many ways of their own, and the cult leader has impregnated Vern, prompting her to flee. The New York Times review of Sorrowland states, “The slow transformation she undergoes while parenting, traveling and finding succor is harrowing and profound, as she fights the horrors of her upbringing and pushes her limits to protect her own children from the physical and spiritual legacy Cainland has left in her.”

Chris Kraus, I Love Dick

This semi-fictional novel feels like it needs no introduction. Chris Kraus essentially writes about her obsession with the critic Dick Hebdige, but really uses her infatuation as a means to interrogate sexuality, art, aesthetics, politics. In an interview in The Guardian, Kraus explains, “What makes something fiction isn’t whether it’s true or not – it’s whether it’s bracketed in time, how it’s treated and edited, and whether it’s construed as a work of fiction.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.