The Ancient Origins of Our Fascination With Flight

Edward McPherson on Why We Can’t Get Enough of the Bird’s Eye View

Humans have always been mindful of the air. Children as young as three or four can use aerial images to find hidden treasure and navigate their neighborhoods; spatial and mapping skills appear across cultures. Something about the airborne imagination seems to be innate.

Consider an ochre and plaster mural painted 9,000 years ago in the Late Neolithic village of Çatalhöyük that, according to some, shows the settlement in Central Anatolia, Turkey, from an imagined blend of aerial and oblique vantages, thus making it not only the oldest landscape painting but also the oldest map—our earliest bird’s-eye view.

A painting elsewhere in the site depicts vultures spiriting away what look like human souls.

Roughly 2,000 years ago, the Nazca Lines were inscribed across 200 square miles of the Peruvian desert, where pre-Incan people brushed aside rust-colored gravel to reveal lines of lighter bedrock to create more than 300 colossal (and stunningly precise) geometric glyphs—of a monkey, spider, orca, condor, hummingbird, lizard, tree, and more, some larger than a football field—that are only legible from above. Of the many motifs, the most common is a bird.

An ancient myth, the soaring king hoping to become an all-seeing god.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that airplane pilots rediscovered the extent of the earthworks, but recent scholarship suggests the meaning of many of the lines might have been less aerial—or even astrological—and more ambulatory, found by walking the ground in a kind of ceremonial procession. After standing intact for millennia, the Nazca Lines suffered during the extra warm El Niño of 2009 their first recorded damage by flooding.

According to legend, when Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.E.) wanted to survey the world he had conquered, he took to the air in his flying machine, a chariot pulled aloft by starving gryphons and steered by lances baited with—according to the source—meat, hunks of liver, or puppies. An ancient myth, the soaring king hoping to become an all-seeing god.

In my office, above a woodcut of Alexander, I tack a small illustration of Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão’s 1709 invention, the Passarola (“great bird”), a purely theoretical airship-glider that—in his petition to the Portuguese king—the Brazilian monk thought to outfit with a stylishly beaded cabin to hold his globes, map, and compass. The pilot peers through a telescope or sextant, flight forever tied to vision.

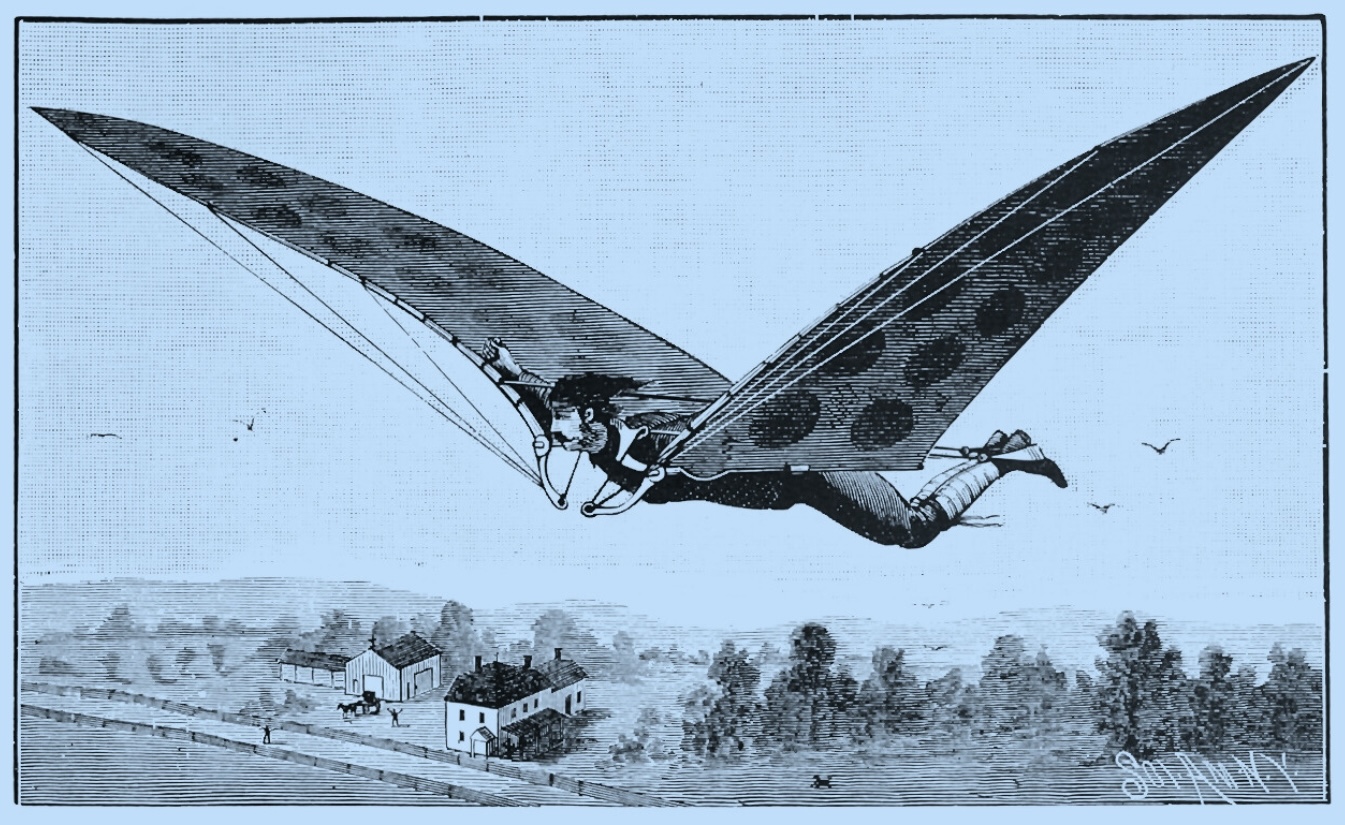

Really, though, of all the feathery fantasies, I’m most arrested by a colorful lithograph of the “Aerostat,” invented by a Dr. W. Miller and published in London 1843. A man soars over a bucolic landscape by pumping a pair of crossed wooden hand-levers that drive a graceful pair of silk wings attached to the lightest of frames from which hangs a tiny board on which perch the man’s patent-leather-shoe-clad feet. He has only a slight, smug smile, but the thrill of flight is conveyed by the aviator’s windswept pageboy barely contained beneath his jaunty cap, a neckerchief whipping from his striped collar. Blocks of text outline the elegantly simple operation—such impossible physics, what rigorous folly!—and yet it seems that if the dapper little gent just flapped hard enough, he might see more of the world than he ever imagined.

During the fourth century BCE, while Alexander was supposedly traveling by gryphon, Chinese engineers began flying kites, which they called zhi yuan, or paper birds. According to ancient texts, by the year 559 the first manned kites, in the shape of owls, carried prisoners as test pilots, often fatally.

Eventually Chinese war kites were strong enough to lift soldiers to spy on enemy positions. Meanwhile, the first Western illustration of a kite—from an illuminated manuscript dating to 1326, De nobilitatibus, sapientiis, et prudentiis regum, or The Noble, Wise, and Prudent Monarch—shows three knights flying a kite over the walls of a city. From the tail of the kite dangles a wicked-looking firebomb.

Around the year 875, Muslim scholar, inventor, and poet Abbas ibn Firnas attached vulture feathers to a pair of silk wings and glided an uncertain distance over Córdoba, in al-Andalus (present-day Spain), before landing and injuring his tailbone. Ibn Firnas was in his midsixties. He never flew again, but his name lives on in a steel-winged bridge in Córdoba, an airport statue in Baghdad, a mall in Dubai, and a crater on the far side of the moon.

By the turn of the twentieth century, cameras were being strapped to kites and even pigeons.

Sometime around 1010, Eilmer of Malmesbury, a young Benedictine monk captivated by the myth of Icarus, fastened a homemade pair of wings to his hand and feet, and threw himself from the abbey tower. According to the book Gesta regum anglorum (Chronicle of the Kings of England), written circa 1125, the monk supposedly flew for a furlong, after which “he fell and broke his legs, and was lame ever after.”

The oldest drawing we have from Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci is an elevated view of the valley outside of Florence that the young artist made on August 5, 1473, to help the city better manage the Arno River.

In 1502, he drew an exquisitely detailed “Town plan of Imola,” so that the ruthless general Cesare Borgia might know the lay of the land he had just captured. Centered in a circle, with four lines crossing at cardinal points, Imola not only appears as it would on a satellite map, but looks like a city caught in the crosshairs.

A military engineer, Leonardo wrote a Codex on the Flight of Birds and dreamed up flying machines such as a parachute, a hang glider, an “airscrew” (proto-helicopter), and a plane with flapping wings. Behind his Mona Lisa stretches an equally bewitching—and often overlooked—bird’s-eye view.

In 1794, during the first of the French Revolutionary Wars, reconnaissance from a hot-air balloon helped General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan defeat the coalition forces at the battle of Fleurus. (Manned ascent in a balloon had been accomplished the previous decade by the brothers Montgolfier.)

During the American Civil War, aeronauts from the Union Balloon Corps piloted vessels such as the Intrepid, Constitution, Eagle, and Washington. Larger balloons were connected to the ground by telegraph wires to speed the delivery of intelligence, which had to be fast, as the tethered gasbags were sitting ducks for Confederate fire. One hundred and forty years later, giant leashed spy balloons—designed for the U.S. Army by Lockheed Martin—would float (unmanned) high over Afghanistan.

In 1858, the French photographer Nadar (aka Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) ascended 262 feet in a balloon over a village outside of Paris and took the first aerial photographs, which—because of the wet-plate process—had to be developed in midair. Those pictures have been lost. Two years later, American James W. Black hovered 2,000 feet over Boston Common and took a photo he called Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It, which—as the earliest surviving aerial photograph—lives not only in the Metropolitan Museum of Art but on the website of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (under “history: defining moments”).

By the turn of the twentieth century, cameras were being strapped to kites and even pigeons. During the First World War, the French would deploy birds to photograph German troops. In the 1970s, the CIA developed its own battery-powered pigeon camera, which weighed (with harness) about as much as a chocolate bar, shot 140 color photos per roll, and could be flown (via bird) over the Leningrad shipyards. Ultimately the fliers proved unreliable, though their missions remain classified to this day.

The brothers packed their gear and returned home to Dayton, Ohio, confident—as they put it to the press—“the age of the flying machine had come at last.”

Finally, at 10:35 a.m. on December 17, 1903, the Wright Flyer, a 12-horsepower, 4-cylinder, 605-pound wooden biplane—with a wingspan of 40 feet, an adjustable double-decker “elevator” protruding from the nose, and two rear propellers to push it along—bobbed through the air for 12 seconds over the Kill Devil Hills, outside Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, with Orville Wright lying prone at the controls as he traveled 120 feet, or twice the length of a bowling lane. Brother Wilbur would make the longest flight of the morning, covering 852 feet in nearly a minute, before slightly damaging the craft.

Shortly after landing, a gust of wind picked up the (unoccupied) plane and dashed it across the dunes; it never flew again. The brothers packed their gear and returned home to Dayton, Ohio, confident—as they put it to the press—“the age of the flying machine had come at last.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Look Out: The Delight and Danger of Taking the Long View by Edward McPherson. Copyright © 2025 by Edward McPherson. Published on October 21, 2025 by Astra Publishing House. Reprinted by permission.

Edward McPherson

Edward McPherson is the author of Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat, The Backwash Squeeze and Other Improbable Feats, and The History of the Future: American Essays. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Pushcart Prize, among other awards. He teaches creative writing at Washington University in St. Louis.