Elephant: Choosing to have none of the answers

A common misconception is that Gus Van Sant modeled Elephant (2003) on Alan Clarke’s 1989 film of the same title. Clarke’s film came out amid sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, known as the Troubles, and depicts 18 assassinations in 39 minutes, with no plot and no dialogue. The accidental viewer, knowing nothing of the film’s source, sees it most clearly for what it is: an unsentimental vision of senseless, anonymous killings. Gus’s homonymous film, about a fictional school shooting in suburban America, is likewise a direct and disturbing echo of real-life horrors. Both films withhold placating answers to the question, “Why?”

The first misunderstanding

Gus suggests that comparisons between the two Elephants have less to do with filmmaking technique and more with societal practices of rationalizing violence. When BBC2 aired Clarke’s Elephant in 1989, audiences familiar with the referenced events could potentially recognize them in the scenes depicted. Nevertheless, they emerged from the film as uninformed as any outsider: the whens and hows of these assassinations are human equivocation next to the frankness of a staggering body count. For its like-minded confrontation with a moral abyss, resistance to rationalization, and also for its unblinking formal qualities, Gus’s Elephant is sometimes considered an artistic exercise closer to Psycho than to Gerry. The episodic cinema documentary The Story of Film: An Odyssey (2011) demonstrates shot comparisons of the two Elephants and lauds Gus as a daring “postmodernist filmmaker” who quotes with self-awareness.

“No,” says Gus, when asked again. “At the time, I had not heard of Elephant. I had not seen the film and knew nothing about it. It was not influential.”

In 1967, on the fiftieth anniversary of the October Revolution, the Hungarian filmmaker Miklós Jancsó was commissioned to make a film celebrating the Bolshevik victory and ensuing establishment of the Soviet Union. Like any prominent filmmaker of his time, Jancsó was fluent in the Soviet propaganda expected of him. He was also fluent in its tacit subversion.

Set in Hungary in 1919, Jancsó’s resulting film, The Red and the White, blurs the distinction between those fighting on behalf of the Tsarist White Army and the Bolshevik Red Army, depicting only their mutual acts of violence. In the end, Jancsó shows the Reds heading toward almost certain, unheroic death. There are no victories, no higher purposes to justify these merciless executions, only an unrelenting vision of clinically perpetrated atrocities. After a brief release, Jancsó’s film was, unsurprisingly, banned throughout the Eastern Bloc.

Along with the films of Béla Tarr (see page 138), The Red and the White, says Gus—this subtle, little-known act of subversion in 1960s Hungary—was an influence for Elephant.

Launching an artistic investigation

Gus watched The Red and the White as an outsider—a person with no connection to the depicted events—and also as a viewer, not a filmmaker. “I watch films as if I’m a member of the audience,” he says, “and if a film’s really working for me, then I watch it again and jump out of it.”

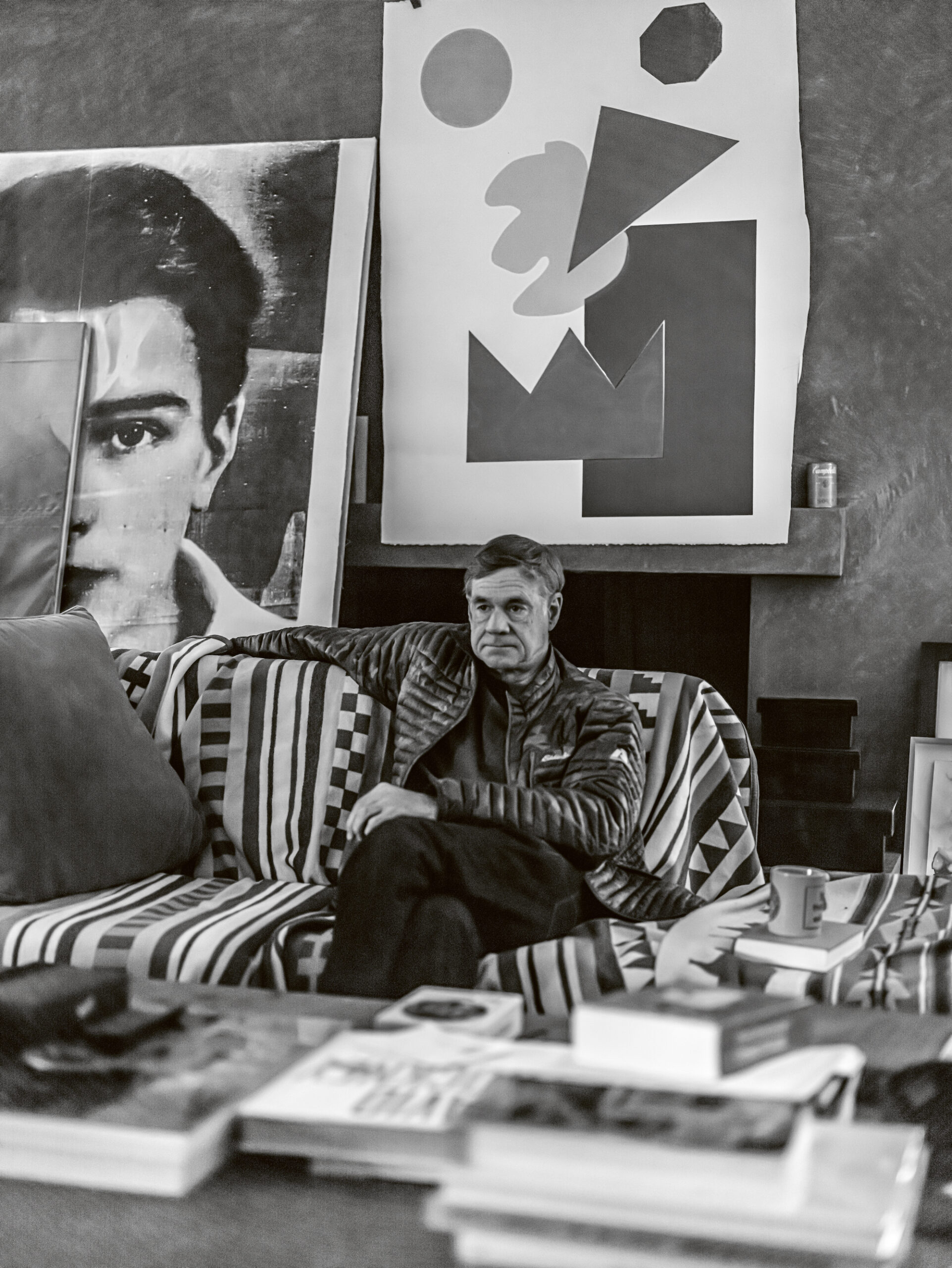

Gus Van Sant in his Los Angeles home, where artworks in progress balance against all available surfaces and stacks of books about art, film, and photography crowd coffee tables and dressers. Photo by Alexei Tylevich.

Gus Van Sant in his Los Angeles home, where artworks in progress balance against all available surfaces and stacks of books about art, film, and photography crowd coffee tables and dressers. Photo by Alexei Tylevich.

Gus first saw Jancsó’s work after Gerry hit the festival circuit. At the time, he was already interested in the rhythms of Tarr and Andrei Tarkovsky, and had recently become intrigued by the Russian director Aleksandr Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002), a lyrical 96-minute film shot at the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, and conceptualized as a single uninterrupted take.

The Red and the White, and other works by Jancsó, precede and influence those of Béla Tarr—and tangentially such films as Clarke’s Elephant—for their experiments not only in sentiment, but also in craft. The Red and the White is characterized by defiantly long takes, measured camera movements that follow excruciating human steps, and the detailed choreography of actors and cinematographer (Tamás Somló, in the case of The Red and the White). The detached, thousand-yard stare of Jancsó’s camera breaks the template of the morality tale. The fog of war never lifts, and the explanation for violence grows harder to see as the film progresses.

Gus made Elephant only four years after the Columbine High School shooting of 1999, when two heavily armed students in Colorado ambushed their classmates and teachers, killing 13. Following this atrocity, American public discourse, by way of magazines and TV network programming, considered many possible patient zeros for this outbreak of youth brutality: Hollywood-scripted violence, video games, and popular music joined the lineup, alongside easy access to firearms and school bullying.

This was a time when ambiguity was creatively more dangerous than taking a clear position. Ambiguity meant that whatever caused this massacre might be entrenched in society: a latent pathology in the every-day lives of Americans, a chronic illness rather than an acute infection cured by prohibiting sales of Marilyn Manson CDs to minors.

Certain subjects were temporarily off-limits to networks, which were under pressure from the U.S. government and public opinion to curb TV violence. During this period in the United States, colloquially called the “1990s culture wars,” conservative advocates pushed for censure and regulation of media programming that they deemed immoral. And here was Gus, amid the chaos, with a pitch for what would eventually become Elephant. “I thought it would be much more specific to Columbine,” then, says Gus, “more literally a TV drama about these two killers,” and an opaque consideration of their mental lives. He also insisted that his project air on television. He wanted to enter the media arena where his work would best register as a direct challenge.

A single meeting at the (ironically titled) cable channel USA, with its owner Barry Diller, demonstrated clearly what this idea was up against. Diller had just returned from the nation’s capital, where fellow cable and network owners congregated around government officials, defending their top-rated shows as ethically sound. In this new reality (predicated on old ideas), Gus’s proposed film received a hard pass. He understood then that approaching network television would be futile.

“The plan had a lot going against it,” Gus admits. “At the time, we’d reached a point where journalism had become entertainment.” Meanwhile “film is generally seen as escapism—that’s why we don’t actually use it to investigate. It would be seen as bad taste to do so.” In Gus’s opinion, that interpretation of dramatic filmmaking is misguided: “I asked myself: ‘Why leave it to the documentarians or writers? Why does it always have to be a bad psychologist asking what happened? Why can’t I ask the questions that a journalist asks for Rolling Stone, or Time, or Vanity Fair? Why can’t a dramatist look into these questions? Why can’t somebody with something different to say try to say it?’”

The banality of evil

Gus began considering the idea of “artistic investigation” after the suicide of Kurt Cobain in 1994. (His film Last Days of 2005, loosely based on the days preceding Cobain’s self-inflicted fatal gunshot, completes the so-called Death Trilogy—after Gerry and Elephant—but chronologically it was the original idea.) In the immediate aftermath of the Columbine shooting, he felt the two violent episodes merge in the anxious collective psyche. “The events at Columbine and the suicide of Kurt Cobain dominated the national conversation, and the analysis was very similar,” he says. “It became a journalistic and public obsession to ask, ‘What happened? What’s the cause?’” He came upon an answer that he knew most studios and networks would find unpalatable.

“So, what happened?” Gus asks rhetorically. “As I got closer to the subjects, the answer grew more elusive. My answer to what happened is: ‘Probably not much. It was probably pretty boring.’”

Indeed, the vast majority of Elephant concerns itself with banality, not bloodshed. In it, the daily experiences of the school shooters blend with those of their victims. Both the shooters and some victims are bullied at school—although not enough to motivate a dramatic turn to violence, at least not by film standards. Both perpetrators and victims face the discomfort of coming into adulthood while still dependent on the flawed adults in their lives. The brief glimpse into the shooters’ family lives is frustratingly functional. Guns are accessed easily—yes, shockingly so, and almost as an afterthought.

The perpetrators skip school to sign for their mail-order semi-automatic weapons, which arrive by standard delivery truck and are brought to their doorstep. As they wait for the package, the shooters lounge in a single-family living room, barely watching a black-and-white Third Reich documentary on TV. “Is that Hitler?” one future killer asks the other, between flashes of swastikas across the dated screen. They are too immature, too ignorant to subscribe to an ideology. Even this scene, so fecund with symbols of brutality, fails to explain their motivation. The swastikas blend with the generic home furnishings of their uneventful suburban lives. The weapons are dropped off by a friendly delivery man.

An outsider—to the Columbine massacre, to American suburban culture, to the culture of mass shootings, and to its surrounding chatter—leaves the film befuddled. Elephant is a mirror held to a confused, contradictory society. The film withholds drama from tragedy and strips it of narrative, a transgression against contemporary moralizing and public discourse. After all, media runs on narrative. Mainstream film, and particularly made-for-TV drama, follows a defined script and formula. These are platforms used to tell stories, construct allegories, and spell out social norms.

“In some ways, we are conditioned to think that paying money for movie tickets means that we should see something we understand,” says Gus. “It’s the same with art. People want a painting to be ‘of something.’ And if it’s not ‘of something,’ it’s, like, ‘what the hell am I looking at?’ For people who need to see a figure, any abstraction is too abstract. Elephant attracted a lot of animosity aimed at it from people for whom it was too abstract.”

Elephant is a mirror held to a confused, contradictory society.Gus’s subversive use of ambiguity in Elephant suggests an homage to those East European filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Jancsó and Tarkovsky, who packaged their films with critical meanings between the lines to get past the censors—and often didn’t make it. In that context, a film predicated on doubt and equivocality was, depending on whom you asked, either a weapon or a threat. The same could be said of Elephant, which Gus made as a comment in progress. The U.S. government did not threaten filmmakers with exile in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but networks and studios did share an implicit understanding of subjects that were off-limits. A strong cultural movement coupled with a 24-hour news cycle stirred federal condemnation and public scapegoating of media deemed violent, sexual, or otherwise corrupting. Funding a project like Elephant, let alone putting your name on it, courted creative exile and public backlash.

Gus was taking a risk, creatively and personally. And after subsequent school shootings in the United States, Elephant did sometimes find itself in media lineups as the latest suspect of moral corruption. Surely, Gus knew all this was a possibility when he embarked on the project. In creating this film, was he prepared to defend himself, critically and personally, from the very sources he was challenging?

Gus grows impatient with this line of questioning. “I’m not making my film so that I can project into the future the kinds of questions people are going to ask me about it,” he says. “You’re saying it’s a risk for me to go into that arena. But then it should be a risk for the journalists, too. And it’s not, for some reason. You’re willing to read a journalistic essay about Columbine, whatever it may say, and that’s perfectly fine. The act of reporting on Columbine is not challenging at all. It’s not wading into sketchy territory. Everyone says, yes, we want to know these things,” he continues. “So if, dramatically, I want to make something that’s more abstract but trying to do the same thing—trying to come up with ideas about what happened? Well, I just don’t feel that has to somehow be scarier for the creator.”

Film deal, compliments of Mr. Soprano

Before Gus abandoned the idea for Elephant, his agent introduced him to the actor Diane Keaton, then working with the premium cable channel HBO. Showing immediate interest in Gus’s proposal, Keaton initiated a meeting between Gus and the then president of HBO Films, Colin Callender.

Gus entered that HBO office with no screenplay, no conventional story development or characters, no star actors attached to it, and no real faith in the meeting. He sold the film as “an abstract piece, something undefined, an artistic statement, like a poem. Something you can pull a lot of different meanings from.” He expected to be laughed out of the room.

Unbeknown to Gus, however, HBO was looking for people like him to start making films for them. The channel had successfully gambled on smart television, including with its premiere in January 1999 of the widely acclaimed and influential series The Sopranos, about the emotional conflicts of depressed mafioso Tony Soprano. It was a complicated show, whose moral compass didn’t always point north, and it was hugely popular.

Newly rewarded for a risk well taken, HBO was emboldened to distinguish itself further from its competitors by signing projects that were too controversial for traditional networks and studios. The idea for Elephant aside, Gus already fit the bill: he was fresh off a daring and contentious cinema experiment (Psycho, 1998) and had recently directed a widely beloved award-winner (Good Will Hunting, 1997) that had made him a household name. Keaton championed the idea of Elephant to HBO and signed her name to the film as an executive producer.

Of course, with Gus’s proposed project, HBO would be hitching its reputation to a subject much more taboo than a humanized mafioso. But the British-born Callender felt they could blaze new trails in known directions. As Callender mulled over the proposal, he remembered Alan Clarke’s film and told Gus, “We can’t make Columbine, but we can make Elephant.”

Although Gus swears he had not heard of Clarke’s film at the time, he says of Callender’s comment: “I knew what he meant. We weren’t going to make a film about a specific trouble, and we weren’t going to dictate answers to the questions around it. We were going to witness the problems we were living through.” From that point forward, the project was always referred to as Elephant.

HBO was ready to greenlight the idea. This should have been the hard part: finding a network to air and fund the project. But the hard part was yet to come. Four years passed before, finally, Gus made his film.

__________________________________________________________________

Excerpted from Gus Van Sant: The Art of Making Movies by Katya Tylevich. Copyright © 2021 by Katya Tylevich. Excerpted by permission of Laurence King Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.