The Advantages of Failure: What Thoreau Taught Me About Journal Writing

David Gessner on the Transformative Power of a Daily Writing Practice

I have known plenty of failure in my writing life. Inspired partly by Henry David Thoreau, I set out to be a writer after college. Which effectively meant that I worked part-time as a carpenter and bookseller for the next dozen years without publishing a word. My current day job is as a teacher in a creative writing program at a university, and if I were to give truly honest advice about how to succeed as a writer to my grad students this would be this: work really, really hard for a really, really long time. Do it every day. Reject rejections, refuse to let others convince you that what you are doing is wrong or not good enough. Build up muscles of nonconformity. And also: sometimes getting angry helps. Show the bastards. Anything that gives you energy. When that asshole at the cocktail party laughs in response to your answer, “nothing,” when he asks what you have published, store it as fuel.

It occurs to me that those years of so-called failure are the best thing I bring to my teaching. It is not hard for me to empathize with my students’ struggles. By my estimate I have close to ten books, not drafts but actual books, that have not been published. One novel I have worked on for over thirty-five years. I hope this does not come off as self-pitying, because I don’t pity myself. I have gained a lot from these books too. And sometimes, as is the case with what I am writing right now, I go back and cannibalize the old in a new way. The moldering books act as nurse logs that feed other projects, nourishing my seedlings.

Then, there are the other kinds of books I write, the ones that I have thanks to Henry. I started the first of these when I was fifteen. My early journals were 5.5-by-8.5-inch sketchbooks, and if I take the very first one off the shelf right now I can read profound lines like: “Joanne Fucking Hart likes me!” Or: “I just got stoned for the first time.” Sometime after college I graduated to the 8.5-by-11-inch journals I still use today. None of them have ever been lined, so I’ve gotten pretty good at writing straight across the page. If you look at Emerson’s journals, which I have held in my hands at Houghton Library, the thoughts are so fully formed, and the script so neat, that they intimidate. Not mine.

Early on I started calling my journals my “swill bins,” where anything goes, including snippets of weather, Dear Diary bad moods, caricatures and cartoons, early drafts of essays and books, and sketches of birds. It loosened me up and gave me an alternative to the novels I was trying to write at my desk every morning. Later, when I began to go on writing-related trips to the Gulf of Mexico during the BP oil spill or following the osprey migration to Cuba, the journals transformed into reporter’s notebooks where I kept transcripts of interviews and drawings of the places I visited. In a pinch, when camping out or in remote places, they were also good for sitting on.

I have known plenty of failure in my writing life.

I now have over 60 journals covering 45 years, and I can pluck one off the shelf and see what I was up to in October of 1991. My early novels were stilted: my characters quoted Thoreau to each other. The journals were natural in comparison, real and lacking artifice. At one point in my development as a writer, I started to consciously try to bring what I called my “journal voice” into my “real writing.” I wanted to sound like I sounded when no one was looking and when I was most myself. I wanted to capture the rhythms of my speaking voice, which, I learned from listening to myself in the journal pages, tends to move from circumlocutious, self-conscious tangents to the blunt and direct. Later, in an attempt to push this even further, I would go on walks in the woods and talk parts of my books into a tape recorder. The goal was and is to sound as much like me as possible.

There is something to be said for this sort of natural writing and natural editing. I tell students about what I call the “Thoreau method.” Walking in the woods, he would see something that caught his eye—light slanting through the leaves of a willow near the river—and then scribble it down on a scrap of paper, no doubt using one of the pencils his family manufactured. Then he would copy what he wrote on that scrap into his journal, rearranging the words as he did, which meant it was in effect a new draft. The journal pages were then copied over for the speeches he gave—another draft—and then, having tested many of the lines in public as a speaker, eventually revised into essay or book form. Thoreau was an early proponent of organic architecture, the outdwelling reflecting the indwelling. So too organic editing.

When I built the first draft of my writing shack by the marsh it was also a kind of “swill bin.” I slammed it together; it wasn’t pretty. But it would become, I eventually began to understand, a kind of physical embodiment of my journal philosophy. I am an early morning writer and I do that writing sitting up at my desk, typing into a laptop. But in the evenings, I walk down to the shack with pen and journal in hand. I am not there to produce anything; I am not there for results. I go wherever I feel like going on the pages. And so, though it is not the purpose, some of that writing ultimately ends up feeding my “real” morning work.

*

Thoreau’s biographer Laura Dassow Walls makes clear that Henry wasn’t quite as obscure or unknown in his lifetime as legend has it. But though one of his favorite metaphors was of a chrysalis, he had no way of knowing that his work would slumber for decades before reawakening for millions of readers. His, or at least his reputation’s, rebirth began at his funeral, where Emerson, whom he had long drifted away from, said: “The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost.” The date was May 6, 1862, and that country, in its second year of a bloody internecine war, had other things on its mind.

I now have over 60 journals covering 45 years, and I can pluck one off the shelf and see what I was up to in October of 1991.

Not long ago, a friend posted on social media that what he would really like to do away with during these times is the imperative voice. I get it: the imperative is the voice of those do-gooders at Thoreau’s door whom he wanted to run away from. But it is also the voice of Thoreau. Henry is all imperative. All musts and shoulds. Even when not explicitly didactic, he speaks in what I’d call the implied imperative. He is one of our deepest thinkers, but at the same time, he is the worst ranter in your dorm room after his second bong hit. And yet, while you could say his words are prescriptive, it is really up to us, his readers, how prescriptively we take them. The prescription, it turns out, might be one we need to fill. Thoreau is astringent medicine. But for now he is necessary medicine.

As with any great figure from the past, we can take what we want and throw the rest away, only wearing the clothes that fit us. I find a lot from Thoreau that I feel I can put to use in these dire times, yet I wouldn’t want to shelter in place with him. He would no doubt look down on my lax and slovenly ways. He wouldn’t want to join me for my nightly cocktail hour down in the shack. “Water is the only drink for the wise man,” he preached. Whatever. I, a child of excess, will never pare down my life to the austere core that he whittled his down to.

But at the risk of claiming to be learning those easy lessons that I discounted when I set out to write this book, and with the foreknowledge that we will one day look back on this pandemic as just another event—as we couldn’t believe we would come to with 9/11, but have—I believe this period will mark a turning point, for me at least. I’m not saying I’m going to succeed, but I am going to try to do with less. And I’m going to make even more of a commitment to turning my thoughts outward, toward the natural world, toward the mystery, a mystery that includes the human but is not subsumed by it. I’m going to try to slow down my life and slow down time, knowing I will fail. I’m going to do the work I love and care about, not merely the work that the world rewards me for. And finally, I am going to try to remember that the work is important for what it is, not how the world regards it.

___________________________________

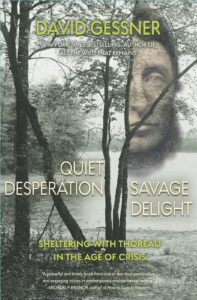

Excerpted from Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis, which is now available via Torrey House Press.

David Gessner

David Gessner is the author of twelve books, including Leave It As It Is: A Journey Through Theodore Roosevelt’s American Wilderness and the New York Times–bestselling All the Wild That Remains. He is a professor in the Creative Writing Department at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, and founder and editor-in-chief of Ecotone. In 2017 he hosted the National Geographic Explorer show, "The Call of the Wild." Gessner lives in Wilmington, North Carolina, with his wife, the novelist Nina de Gramont, and their daughter, Hadley.