The Addict as Archaeologist: Telling the Hard Stories of Family Tragedy

Steven Wingate on the Long Journey to His Latest Novel

The first and only time I dropped acid was at 19, with both my brothers. Tom, the eldest, had driven down from Massachusetts to pick me up in Binghamton, NY and go visit Mike, our middle brother, in Norristown, PA. We hadn’t all been together in at least six years, when the family blew up in the aftermath of our father’s death and I moved with my mother (who wasn’t their mother) to Colorado. I missed them, but I didn’t quite know them anymore.

On our first morning at Mike’s row house we did the acid, with my brothers deciding on a safe dose for me. They both considered me a drug dilettante, since all I’d ever done was drink and smoke pot, and they didn’t let me try to be macho. This was long before Tom went straight and took his life back, long before Mike lost his to heroin entirely. We wandered out into the run-down streets of Norristown, with its Rottweilers and chain link fences topped by razor wire, and headed for the railroad tracks.

My brothers hadn’t pressured me into the acid at all, but I wanted to take it as a test to see if I was crazy or not. If I was, LSD would blast open the cracks in my mind and I’d end up in a nuthouse. This would solve a lot of problems, because I’d never again have to wonder what to do with my life. If I wasn’t crazy, then I guess I’d have to trudge on.

We walked down the tracks and found a small bandshell with rows of benches facing it, and Mike and Tom splintered off to sit in the first row and cry together. Their mother had died when they were toddlers, and my mother had been cruel to them, and they’d both given up control of their lives to addiction. They had plenty to cry about.

It wasn’t my conversation and they didn’t invite me into it, even though I’d completely screwed up my own life and was about to drop out of college a second time from too much partying. My brothers had their own shared life before I came along and I wanted to give them space, but I couldn’t go too far away because I didn’t want to be stumbling around on acid in a town I didn’t know.

So I walked, slowly and deliberately, between the rows of benches. Every time I turned to switch rows I’d look over at Tom and Mike and come up with a new story about why the two men up front were clutching each other and crying. I’d race through the story with my acid-y imagination, round the bend to the next row, and come up with a fresh one when I saw them again.

The first and only time I dropped acid was at 19, with both my brothers.

When I got to the last row, it hit me: I’d spent my youth with Tom and Mike making up stories about lives I could observe but not participate in, and that’s what turned me into a writer. I needed stories to make me feel belonging, even if I had to invent them. Sure, it was an acid revelation, but it stuck with me. It doesn’t matter where truth comes from, especially if you’re desperate for some.

*

In my youth I spent a lot of time observing tales of addiction and the ruins it leaves behind. Substance abuse was a big deal for many men in my family, a badge of fuck-it-all, macho courage. My uncle Eddie drank himself to death by 37, and booze helped finish off my father by 42. I’d be a fool to pretend addiction wasn’t in my DNA. My own generation had newfangled temptations, and after watching my brothers struggle with them I’m inexpressibly grateful that I got the low-calorie version of the addiction gene. Tom eventually got sober, then made helping other people get sober the centerpiece of his life. Mike continued slipping into the darkness that I only flirted with. I’ve caught myself crawling toward the abyss a few times, but I’ve never fallen over the edge and been forced to wrestle with the demon the way my father, uncle, and brothers did.

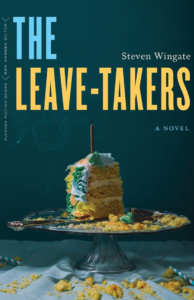

But I know the taste of addiction because it was in the air around me, just like the sweet smell of the Nabisco factory in the New Jersey town where I grew up. I’m called to witness it, and have been writing addict characters as long as I’ve been writing fiction. My main addiction project was The Leave-Takers, a novel about two pill-popping orphans in love, and the male protagonist’s brother was a junkie like Mike. From the very first draft in 2003, I wrote it knowing that I’d someday have a brother whose addiction killed him. I kept circling back to The Leave-Takers after substantial breaks, the way lifelong addicts like Mike circle away from and back to their temptations. He’d go clean for months and we’d talk regularly on the phone about the past, or his guitar playing, or my writing. Then his need would take over and he’d ask me for money and disappear until the next time he declared himself clean.

If I had a complete chart of my emotional life, it would probably show that I worked on The Leave-Takers when I was most afraid of slipping into darkness myself. Having the low-calorie gene didn’t save me from addiction’s emotional cycles, it just made the whirlpool I kept getting sucked into harder to drown in. I went through the same ups and downs as Mike, and sometimes we even fell into sync, but the peak-to-trough amplitude of my cycles was smaller and more manageable.

Around 2008 Mike and I got into a fight over my mother and a poem I’d written, and we stopped talking. Tom kept me posted on him, and I passed on the message that I’d be open to a phone call to patch things up. It never came. Then, as was inevitable, Mike died in March 2016. He was six-four like me, and more athletically built, but he weighed only a hundred pounds when Tom tracked him down at a hospice for the homeless in Philadelphia. I almost flew in from South Dakota, but backed off because neither Tom nor I could predict how Mike would react to me. I managed to get a message to him through Tom before he died, and he received it with grace, and our spirits are reconciled, and that’s all I’ll say.

When I got to the last row, it hit me: I’d spent my youth with Tom and Mike making up stories about lives I could observe but not participate in, and that’s what turned me into a writer.

The Leave-Takers changed once Mike died. I saw I’d been nurturing my little share of the family curse called addiction like an open wound, letting it scab over just enough so I could pick at it. The novel was a delayed confrontation with addiction, and I couldn’t keep putting it off if I wanted to feel like an actual person instead of a shadow in my own life. In its post-Mike drafts, my husband-and-wife protagonists got deeper into their pill problems, and their addictions bit them harder than I’d ever allowed before. I let their addict genes scare them more because my addict gene scared me more. Losing two men in my family to addiction could be passed off as rotten luck and poor decision making, but losing a third was definitely a warning siren.

Revising the novel after Mike’s death revealed to me how thoroughly I’d harbored, fed, and given safety to addiction. I drank almost every night, though because I only drank a little I believed my own bullshit about booze not being a real problem. I stashed pills from my recurring back injuries for those just in case moments down the road when I’d want a little break from myself, and I believed my own bullshit about only taking them for truly debilitating pain. I let the cycles of addiction shape my life not out of homage to my addicted loved ones, but because I had a problem of my own—an open invitation to minor-league oblivion that will never go away.

For decades I did nothing to keep addiction at bay beyond reassuring myself, with a hubris I saw only after my brother died, that I wasn’t as much of an addict as the most afflicted men in my family. When the novel taught me what I’d done to myself, the birds of addiction that had swirled around my family since long before I was born lined up on the telephone wires of my life. They said You’re not immune. They said Your brother Mike didn’t pretend, so why should you?

Finally finishing The Leave-Takers solved zero problems, but it did slap me in the face and remind me that I can’t afford to have days when I don’t count the birds of addiction up on their wires. As the book goes out into the world almost exactly five years after Mike’s death, I wonder why he had to die for me to finish a novel about something that has not only filled the air around me for my entire life, but has actually filled me for my entire life.

*

Addiction is about different things to different people, and for me it’s about fear. When I find myself tripping over addiction—slamming a margarita because I had a shitty day, reaching for a pill to chill my nervous ass out—I can always scratch in the dirt at the edge of my psyche and find some fear that has just become unburied. None of these fears are ever new. They’re primal fears everybody knows, like abandonment and meaninglessness, but they’re also geniuses at disguise. They seem at first to be inconsequential and merely bothersome, like somebody else’s shoes clogging up a doorway.

If I had a complete chart of my emotional life, it would probably show that I worked on The Leave-Takers when I was most afraid of slipping into darkness myself.

The addiction-related deaths in my family have taught me to kneel down and dig at the annoyances I trip over, because they’re actually primal fears with new faces. If I don’t dig around and identify them, everywhere I walk is cluttered with opportunities for fear to trip me up. Every time fear activates the addiction inside me, it wins—and it rewards itself with more opportunities to tempt me via booze and pills.

The best way to keep addiction from tapping on my shoulder is to spend lots of time on my knees like an archaeologist digging out an ancient temple. The temple I’m excavating is dedicated to my own low-calorie addiction, and it’s a lot like the temples other men in my family built to their burlier, angrier addictions. Though the specifics of these temples—the color of their interior walls, the placement of their sacrificial niches—varies from person to person, the layout is roughly the same. Having grown up in them, I know where the entrances are, where the high altar is, where the old junk gets stored.

What I don’t know is where the fears are buried and what disguises they’re wearing at any given moment. Though I can take a bird’s eye view and see the scope of work ahead of me, I still have to dig the temple out by myself so I can identify those fears and create paths around them. If I always let my fears get unburied by circumstance alone, I’ll always be tripping over them and giving addiction more chances to win.

Knowing the general layout of a temple to addiction isn’t enough. I thought it was for decades, until Mike’s death and rewriting The Leave-Takers set me straight. The only way forward is for me to patiently and systematically excavate my fears. I’ve got to stay on my knees and dig out the temple until I expose it all—every friendship I’ve broken, every promise I’ve escaped. The temple’s power over me won’t be exorcised until I can walk through it without watching my feet and worrying that I’ll stumble over a cleverly disguised primal fear.

Everyone who digs through the archaeological site of their own addiction has to do so a few square inches at a time. The digging is slow, laborious, and dusty, and it keeps us from many other productive and enjoyable activities. It’s a life’s work for many of us, and should be for many more. I dig because I want to turn the edifice I’ve built into a temple of something other than addiction, and I believe this structure can be repurposed. It’s my choice what I put on the high altar, isn’t it? I can leave the implacable need of addiction there, or I can replace it.

What will I put on that high altar if I can dig my way to it? Peace, sure. Wholeness, sure. Or something I find along the way, a bright and buoyant piece of self left behind long ago that I buried with my own hands and forgot.

__________________________________

The Leave-Takers by Steven Wingate is available now via University of Nebraska Press.

Steven Wingate

Steven Wingate is the author of the novels Of Fathers and Fire (2019) and The Leave-Takers (forthcoming March 2021), both part of the Flyover Fiction Series from the University of Nebraska Press. His short story collection Wifeshopping (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008), won the Bakeless Prize in Fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. He is associate editor at Fiction Writers Review and associate professor at South Dakota State University.