The Accidental Origins of the “Subway Book Review”

Uli Beutter Cohen on How She Started Documenting New York’s Subway Readers

To write about the entirety of New York City is an impossible thing to do. The city is too grand yet too personal, too elusive yet too concrete. When we talk about the city, we can’t just describe a place and its people, a dream and its destination. When we talk about New York, we have to talk about the world, which gathers here to find itself. The place that singularly illuminated for me what connects us on this journey, is the underground.

I arrived in New York City in 2013 and felt like I was late to the party. Many of my friends were lifelong New Yorkers who had already lived through the best and the worst of times. Others I knew attempted to move here and left after a few years, defeated. What sparked my curiosity was the promise of extraordinary stories. I couldn’t wait to meet the people who called themselves New Yorkers and whose sheer existence in such an unpredictable and relentless place seemed to hold some kind of secret.

After I landed in a Brooklyn sublet with no air-conditioning during a particularly hot summer, I had a hunch that my boundless enthusiasm would not last forever. I needed to observe the city with fresh eyes while I had the chance. I signed up for workshops and classes, went to parties and events, joined and formed artist groups, and spent every free moment walking through all corners of the city, ferociously inhaling its newness. However, my approach quickly proved to be too broad and therefore quite futile. People didn’t have time!

Neighborhoods were changing overnight! As soon as I felt familiar with someone or someplace, they had already moved on. But between destinations, something caught my eye. The subway. It connected the dots.

Unlike the streets aboveground, the subway slowly, if ever, changes.

It’s the city’s beating heart that never stops. It’s also one of the few places where the ever-rushing inhabitants of New York City have to stand still—if you can get on a train to begin with. Countless times I swiped my MetroCard at the Clinton–Washington Avenues station only to find out that it was empty yet again, which often caused me to miss my train. At the vending machine, I faced the innocent but profoundly existential question of whether I wanted to add value or time to my card—a choice that could really stop me in my tracks if I let it.

During rush hour, I squeezed into a funny shape to avoid being thrust face-forward into a stranger’s armpit. Feet stepped on other feet. Eyes avoided other eyes. Hands felt for a spot on the handrail that wasn’t warm or wet. At every station, more people packed their bodies into nonexistent spaces, creating a tight, involuntary group hug. As a small-town girl from Germany who had spent a decade on the West Coast living at a more leisurely pace, I was immensely frustrated and equally fascinated by the subway.

The more I talk to readers in the underground the more I realize that books are a reflection of our identities and souls.

When I discussed the G train’s erratic behavior in one of my artist groups, it hit me. Since I believed in the “finding-clarity-in-chaos” theory, was the subway a portal to a side of the city where I would find something extraordinary? I decided to follow my instinct and started to ride the subway whenever I could, at all hours of the day, with no destination in mind.

On a cold winter morning, I rode the B train over the Manhattan Bridge.

I stood by a window because I loved seeing the East River and the Statue of Liberty, with her torch gleaming in the sunlight. The train was fairly empty. It was one of those days where it was so quiet, you’d think you were the only person in the city if you closed your eyes. As usual, I looked up and around, unlike others, who were sleeping or busy with their phones. Unexpectedly, my gaze met that of a young woman at the other end of the train. Our eye contact lasted much longer than subway etiquette allowed. It was uncomfortable and it also felt like an invitation. I decided to go over to her and, since she held a book in her hands, ask what she was reading.

Hana told me she was a sci-fi fan, which explained Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins, and that she was on her way to a rehearsal at the dance company Alvin Ailey. Spontaneously, I jotted down our conversation and asked if I could take Hana’s picture to commemorate the moment. She agreed. We only rode one stop together, but I felt electrified. I had caught a glimpse into another world.

After talking to Hana, the subway became my unofficial office and my second living room. I surrendered to its oceanic flow, and with every ride I understood the city, its layout, and its boroughs a little bit better. I felt how the collective mood of the city would shift based on current events, and I started to see who I shared space with. The subway carried people from all seven continents, of all ages and backgrounds. Enemy nations gently touched knees on rows of plastic seats.

This diversity wasn’t restricted to the commuters—it also extended to the literature they held in their hands. I saw people with bestselling novels, experimental poetry collections, self-help books brimming with sticky notes, provocative memoirs, and well-loved classics. When I asked about their choice of book, each reader had their own story, too—stories I began to document. The conversations lasted longer and grew deeper. I put more care into my photography and asked more questions. I started to understand the importance of storytelling by the people for the people, and that local stories, much like local food, create a different connection to your home. Slowly but steadily, my experiment evolved into a place for community.

Over the last seven years, Subway Book Review has become many things to many people. Some say it’s a movement. Some say it’s a social media project. To me, it’s a documentation of who we are and where we are going.

The more I talk to readers in the underground—unquestionably some of the most imaginative and empathetic people—the more I realize that books are a reflection of our identities and souls. Books reflect everything we are and everything we wish we could be. At Broadway–Lafayette station I met Verena, who read No One Tells You This, and talked about living a meaningful life as a child-free woman. At Columbus Circle, Saima told me that They Say, I Say helped her to address hurtful confrontations about her hijab. Larry shared his experience as a foster kid in Queens with me during a conversation about Becoming. Emmanuel read De perfil and described what it felt like to be a Mexican immigrant in today’s America.

I also started to connect the dots aboveground. M Train by Patti Smith and a chicken coop sighting in the middle of Brooklyn brought a grieving photographer named Ellie peace after her mother’s passing. Her story made me want to find the person behind the chicken coop. It took a few months, but eventually I sat down with Gregory Anderson, the man who had built not one but several chicken coops all over the city in response to 9/11. Some conversations I had a chance to revisit, like the one with Kamau Ware, who became one of my closest friends over our shared love for public spaces.

Others were fleeting. I’ll never forget the day in 2018 when I randomly saw Ta-Nehisi Coates on the 6 train, reading Ill Fares the Land by Tony Judt. We only rode one stop together, but his generosity filled me up as if we had sat down for one hour. Other people, like Jacques Aboaf and Ashley Levine, I ran into multiple times in different parts of town. Each conversation opened up a chapter about dreams, fears, hopes, and secrets. Each encounter seemed less like happenstance and more like an intentional opportunity to broaden my horizons.

Like the city itself, I’ve had to evolve and adapt over the years. The arrival of the internet service on subways in 2017 meant fewer commuters with printed books in tow. Sometimes I saw a promising-looking tote bag and was delighted when someone revealed their current read. In addition to talking to strangers, I also started to ask interesting people to meet me at their favorite subway station. In 2020, when the pandemic and white supremacists turned our lives upside down, I interviewed people over the phone, like Waris Ahluwalia and Jamel Shabazz, or met them outside at a distance, like Wendy Goodman. But even as we experienced the unfathomable, we shared our journeys and we felt close.

Between the Lines is a collection of some my favorite encounters. Each one has shown me that our connections are endless. I’ve talked to people in all five boroughs. I’ve ridden every train line end to end. I’ve laughed, cried, and hugged more strangers than I can count, but of course not all conversations have been easy. Some hit my blind spots, and some hurt my soul. I’ve heard personal accounts of loss, discrimination, hate, and other threats that many people face daily and desperately wish to escape from. Each book built a bridge, not just for the readers but also for me, leading into other lives and possibilities. Each story gave me the chance to learn and unlearn what I thought about my place in the world.

After talking to over a thousand people, I’ve come to realize that these conversations aren’t about one person’s knowledge or lack thereof. The point is to share each other’s reality and truth for a moment.

_______________________________

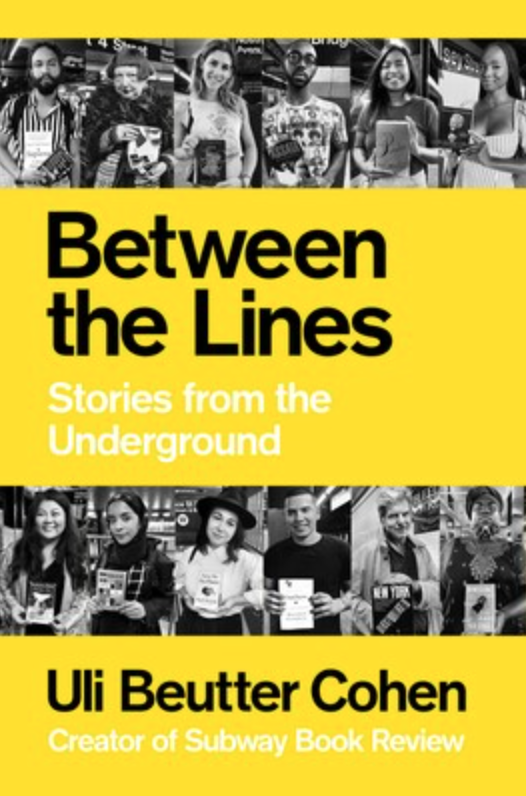

Uli Beutter Cohen’s Between the Lines is available from Simon & Schuster.

Uli Beutter Cohen

Uli Beutter Cohen is a New York City–based documentarian, artist, and the creator of Subway Book Review. She explores belonging to a time and place through writing and photography. Uli is a sought-after speaker and panelist. Her work has been featured in print, on TV, and online by New York magazine; Esquire; Vogue; Forbes; O, The Oprah Magazine; Glamour; the BBC; and The Guardian, among others. Between the Lines: Stories from the Underground is her first book. Uli lives in Brooklyn. Visit @TheUBC, @SubwayBookReview, and SubwayBookReview.co to hear more.