The 50 Greatest Coming-of-Age Novels

Summer's Almost Over . . . Just Like Your Childhood (Sorry)

Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing

Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing

Ward’s latest novel begins on Jojo’s thirteenth birthday, which is also the day he finds out that his father is being released from prison. Thus begins a road trip increasingly haunted by both past and present, which will teach Jojo something true about his own myths, and those of his family. See also: Salvage the Bones.

John Irving, The Cider House Rules

John Irving, The Cider House Rules

Irving’s classic concerns Homer Wells, growing up in an orphanage (so many orphans on this list—perhaps Tom Gauld knows why) and helping its director perform abortions—until he finally decides, as a young man, to leave the place he’s lived all his life and fall in love with a woman whose boyfriend might or might not be dead and who might or might not come back paralyzed but still ready to marry her, forcing them to keep their love a secret, etc.

Vyvyane Loh, Breaking the Tongue

Vyvyane Loh, Breaking the Tongue

Like Midnight’s Children, this novel blends the personal—the coming-of-age of Claude, a Chinese boy whose parents are such Anglophiles that he has never learned his mother tongue, with the political—the fall of Singapore in World War II. Claude’s narration alternates with that of Ling-li Han, a nurse he encounters; his journey is punctuated with an experimental ending. As Julia Lovell describes it in The Guardian:

At the heart of Claude’s cultural discomfort lies his inability to communicate in the language that defines his ethnic group. When British authority, and Claude’s faith in it, disintegrate, he sets about learning his mother tongue, and it is in untranslated Chinese that, in the closing pages, he recalls Ling-Li’s last, horrifying moments in a Japanese prison cell.

Sarah Waters, Tipping the Velvet

Sarah Waters, Tipping the Velvet

In this highly delicious debut novel, a teenage “oyster-girl” called Nan falls in love with a male impersonator at the local theater, and follows her when she goes on the road, first as a friend and costume manager, then as a lover and co-star—until everything, as it always does in Waters’ novels, crumbles disastrously to the ground, leaving Nan destitute and miserable. Her real coming of age, of course, comes from what happens after all that.

A brilliantly observed boarding school bildungsroman that doesn’t get nearly the credit it deserves.

This compelling novel also features one of the best opening lines in contemporary literature: “My father, James Witherspoon, is a bigamist.” Don’t tell me you won’t keep reading after that—especially because what follows is the double-coming-of-age of Dana Lynn Yarbor and Bunny Chaurisse Witherspoon; when it begins, the former knows all about the latter, who knows nothing—but soon will.

Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

We often think of coming of age stories as being small, localized to the journey of a single person—who often starts out as a literal child, no less. But they can also be massive, engaging with major historical events while they tackle the personal ones, as Midnight’s Children does with its magical realist take on India’s independence—and the boy who is exactly as old as his country.

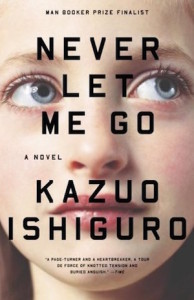

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Yes, even clones can come of age. As Joseph O’Neill put it so eloquently in The Atlantic:

Ishiguro’s imagining of the children’s misshapen little world is profoundly thoughtful, and their hesitant progression into knowledge of their plight is an extreme and heartbreaking version of the exodus of all children from the innocence in which the benevolent but fraudulent adult world conspires to place them. We grow up—if we’re lucky—in security and wonder, and afterward are delivered to the grotesque fact of our end. And then?

No and then.

Zadie Smith’s 2000 novel is both a family drama that spans three generations, and a coming of age novel for Millat and Irie, second-generation immigrants living in London. A modern classic.

I suppose King’s novella The Body would be a more obvious choice here, but It is more fun—and after all, fighting an ancient unnamable evil with your friends and escaping with (most of) your lives is rather more character-building and innocence-destroying than just, you know, seeing a dead body.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.