The 36 Best (Old) Books We Read in 2021

Timeless Reading Recommendations from the Lit Hub Staff

I know, I know, it’s December, we’re all contractually obligated to tally up the Best Books of the Year That Was—and don’t worry, we will. (No shade to book lists, end of year or otherwise; they are, as Eco reminds us, a cultural bulwark against death. Also they are fun.) But as your father says, age before beauty, and so before we take the measure of the new kids on the block, the Lit Hub staff would like to celebrate some non-2021 books that we discovered (or re-discovered) this year.

After all, one of the great things about books is that they don’t disappear after the first year of their publication—barring floods and thieves, they can loiter forever on your shelves, waiting to be picked up and rediscovered, manic publicity cycle be damned. They can be revisited, loaned out, traded, forgotten and found. They can have strange, long lives. And hey, sometimes you’re just in the mood. So here are the older books we’ve been reading this year, whether for the first or the tenth time.

Mordecai Richler, Barney’s Version (1997)

I am not a huge re-reader, but in the middle of a rainy weekend bookshelf alphabetization disaster I uncovered Mordecai Richler’s Barney’s Version, a book I read a decade ago in an MFA class called “The Hysterical Male” taught by Gary Shteyngart. I remembered the very end of the book scene by scene; I also remember finishing the book exactly at my subway stop and uncontrollably crying, much to the absolute terror of everyone around me. Either because I was aware the organizational project was soon going to break me or because I needed a distraction, I found myself spending the rest of the weekend with the curmudgeonly Barney Panofksy, self-described “wife-abuser, an intellectual fraud, a purveyor of pap, a drunk with a penchant for violence and probably a murderer.” It is an exceptionally fun book to read, and from a craft perspective, Richler’s mastery of both voice and unreliable narration still feels surprising. Thoroughly recommend for a first, or second, read. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Sebastian Castillo, Not I (2020)

Sebastian Castillo’s Not I is a book of accumulation. It has twelve sections, one for each of the English language’s verb tenses; each section uses English’s 25 most common verbs to create a series of first-person sentences. The maybe-Sebastian, maybe-nobody, maybe-everybody speaker catalogues the quotidian: “I make toast.” “I go to the park.” “I will be getting surgery tomorrow.” And the emotional: “I felt depressed.” “I thought you were my friend.” “I felt sorry for myself.” The speaker bends to authority figures; indulges in moments of luxury; longs for closeness; worries about doctor’s appointments. In mapping the everyday, Castillo’s doing something close to Perec’s idea of taking an account of the infra-ordinary, but with an inventory of time instead of space.

For Not I is concerned with the end. Juries, judgments, and grades make recurring appearances. “I have accumulated the bits of my life,” says maybe-Sebastian. And: “I will have called it the past.” Not I is aware and skeptical of the urge to accomplish, to turn your life into something you can look back on and feel pride. (Like, a book.) But its format knits the past to the future, promising that even banal experiences add up. When the book hits future tense, the sentences read like mantras, and the future experiences start to feel like the reader’s. It becomes a book of faith: look at all we have done, we will do, we will have done. –Walker Caplan, Staff Writer

John Lanchester, The Debt to Pleasure (1996)

This month, in anticipation of the holidays (read: food, family, the desire to murder) I re-read one of my favorite novels that no one else seems to have heard of, and found it to be just as pleasurable and wicked as I remembered. English novelist and journalist John Lanchester’s debut, published in 1996, takes the form of a loose cookbook, and also a memoir of a childhood strangely studded by mysterious deaths, and also, as you slowly discover, a real-time stalking diary. I won’t say any more than that, plot-wise, except that I was struck, re-reading this 25 years after its original publication, with how slow and subtle the reveals are; surely that would no longer be allowed in a novel like this.

But why not, when the real propulsive tissue is the narration, through which Lanchester goes out of his way to give you little jolts of wicked pleasure, which is always what I’m looking for in a reading experience, and the specificity of the voice: gloriously snotty, ironic, and opinionated. “There is an erotics of dislike,” our narrator tells us early in the book. “To like something is to want to ingest it and, in that sense, is to submit to the world . . . But dislike hardens the perimeter between the self and the world, and brings a clarity to the object isolated in its light. Any dislike is in some measure a triumph of definition, distinction, and discrimination—a triumph of life.” I have been affirmed. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing (2019)

If you’ve been keeping up with the news, you’d think that the “Great Resignation” was a serious threat to American enterprise and gainful employment. According to fearmongering CEOs, no one wants to work anymore. Anyone who’s had to work a non-salaried job knows this isn’t exactly true. It’s not that people don’t want to work—people (especially workers of color) don’t want to keep grinding away at low-wage, dead-end jobs run by abusive managers. And add the fact that our planet is dying right before our eyes, it’s enough existential dread to make you feel like you’re sitting in a room on fire, just waiting to burn up. So how do we save ourselves from submitting to total despair?

Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing is the perfect antidote to our workaholic, overstimulated culture, where a person’s worth is tied to their capitalistic value. Of course, the title is not meant to be taken as literal advice. Instead, the act of doing “nothing” is framed as a return to self and active resistance to the death-drive tendencies of productivity. Odell champions tools that are based on cultivating community rather than breakneck competition. The power of nature also cannot be underestimated. For Odell, freedom is not achieved through isolation but reinvestment in the senses, a sincere commitment to living rather than simply existing. –Vanessa Willoughby, Assistant Editor

Jeffrey Eugenides, The Marriage Plot (2011)

Few topics are as fascinating to me as the romantic relationships of others. I love a romantic comedy not for the happy ending so much as the representation of the private moments between a couple. The Marriage Plot combined relationship voyeurism with coming-of-age, and wrapped them up in (the aforementioned) plot that was brisk and readable in the best sense. It was exactly what I needed this year: a genuinely fun read. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

Mark Sundeen, The Unsettlers (2016)

I’m fairly certain that until the day I die I will be exceedingly curious about the ways in which other people have chosen to live; particularly those who’ve committed to living outside—and in resistance to—the exigencies of contemporary hypercapitalism. Apparently Mark Sundeen shares this curiosity and went so far as to write a wonderfully thoughtful, deeply reported account of three very different families and their Sisyphean struggle to live according to their principles. From an urban farm in post-industrial Detroit to a neo-Luddite community in northeastern Missouri to the vanguard of organic cultivation in Montana,The Unsettlers shows us just how hard it is to escape capitalism’s twin systems of extraction and consumption, and why it’s crucial that more than just a few of us try to. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Toni Morrison, Tar Baby (1981)

This is one of those books I read incredibly slowly just to avoid finishing it. Though often described as a love story between Jadine—a Sorbonne graduate and model—and Son—a runaway who finds himself in the Caribbean island where Jadine and her patrons live, the novel plunges deep into the aliveness of things: history, plants, water, youth, and age. Everything moves on the page and everything has a hand in telling the story. And like any Morrison, it’s the language that lingers long after you’re done reading. My personal favorite line goes: “It was a silly age, twenty-five; too old for teenaged dreaming, too young for settling down. Every corner was a possibility and a dead end.” –Snigdha Koirala, Editorial Fellow

Patricia Highsmith, The Price of Salt (1952)

To my great shame, I must confess to never having read a Patricia Highsmith novel before 2021. Despite my love of the film adaptations of Strangers on a Train, The Talented Mr. Ripley, and The Price of Salt (aka Carol)—all of which I consider to be masterpieces—I never bothered to walk the quarter mile to my local used bookstore and spend the price of a pint on a battered paperback by the troubled poet of apprehension. What a fool I was. The atmosphere of unease Highsmith conjures in her novels is thick enough to choke, and this tale of sexual awakening, obsession, and liberation is (despite being, I think, murder-free) no exception. The story of a disaffected New York set designer/shop girl who becomes infatuated with a glamorous suburban housewife, The Price of Salt is also a tender, bitingly witty, and surprisingly hopeful love story. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

Nora Ephron, Heartburn (1983)

If you’ve seen You’ve Got Mail and When Harry Met Sally a thousand times, as I have, it’s perhaps time to venture into the rest of Nora Ephron’s oeuvre. Reading this novel feels like watching one of her beloved movies, at a tilt. It comes with all of her signature wit, but it’s by no means a romantic comedy. (NB: Heartburn was, in fact, adapted for the screen. Directed by Mike Nichols and starring Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson, it’s definitely not what you’re expecting. But the book! The book feels closer to classic Nora.)

Reader, meet Rachel Samstat. She writes cookbooks for a living. She’s a devoted wife, a doting mother, she’s pregnant with her second child—and then she finds out her husband is having an affair. The rat bastard! For a book that revolves around such devastating discovery, it’s unexpectedly light. We have our effervescent narrator to thank for that. She’s smiling through her tears! She’s finding something funny in the tragedy! And she’s doling out tips for a killer vinaigrette! –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

James Galvin, Resurrection Update (Collected Poems, 1975-1997)

This year (the long year that won’t end?) has been hard for us all. Some have turned to baking, others to booze, and most of us to binge-watching tv… Somewhere in there I have found myself reading even more poetry than usual, particularly the early collected poems of James Galvin. Galvin’s spare, lyric intelligence—whether it’s alighting on the sun-weathered bones of a long dead family horse, or cycling through the tenderest moments of a long-ago affair—never fails to jolt me out of my small, daily miseries. Here is the perspective you need, these poems all seem to say, whether you want it or not. –JD

Louise DeSalvo, On Moving (2009)

Wow oh wow did I love this literary examination of moving from the wonderful, late Louise DeSalvo. Inspired by leaving behind the house in which she’d raised her children, DeSalvo turns to literary figures—Percy Shelley, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bishop, and others—to understand how their moves affected their lives and work, for better and for worse. One gem to take with you: Woolf wrote about her compulsion to move as “this ancient carrot before me” (possibly my favorite metaphor of all time?). –Eliza Smith, Audience Development Editor

Henry Roth, Call It Sleep (1934)

Call It Sleep came to me via a very enthusiastic recommendation from a friend and in the middle of a few weeks when I was having trouble concentrating on just about anything. It fixed that; I’ve rarely read anything as absorbing as Henry Roth’s narrative of a young boy’s life in the Jewish immigrant ghettos of New York City in the early 20th century. Published in 1934, Call It Sleep was Henry Roth’s masterpiece, and after writing it he didn’t publish anything for decades. His fluid and dynamic writing perfectly captures all the chaos and confusion of being a young child—particularly in the case of protagonist David, who is besieged by an abusive father, protected by a warm and loving mother, and facing all the challenges that come with growing up between cultures. To read this book is to fully enter a child’s life in all its delight—and, sometimes, its terror. A cacophony of voices fill David’s world, from the Yiddish of his childhood home to the strange and unfamiliar call of authority figures and the accents of the various communities around him; Roth weaves them together to create a profound portrait of the way a child tries to piece together the world. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

James Salter, Light Years (1975)

James Salter is the master of slow, sensual storytelling—and I mean that word, sensual, in its most literal definition. Every scene is set by the smell in the air, the light on the worn rugs, the skirt tapered to the knee, the music playing from the phonograph. A supreme amount of pleasure is taken in these small details that collect and spill all over the pages, details that add up to depict full, warm, tangible lives. Everything is done in the way it should be: cocktails by the fire, games for the children, dinner parties in the country. The evocative elegance of the language almost deems plot irrelevant, but only almost. It is the marriage of Nedra and Viri we are there for, whose domestic rituals we follow: we’re there as they love each other, as they turn from one another. And when things unravel, when separations occur, as do death and illness, even still, Light Years leaves you convinced that life is beautiful, and worth living for the dailiness. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (2018)

I am happy that beloved anarchist anthropologist David Graeber has become a household name (in certain households, anyway); but I am sad that he’s not around to read all the wonderful profiles and reviews occasioned by his posthumously published Dawn of Everything (written with David Wengrow).

Earlier this year, when I had to sand a floor, I listened to the audio version of his previous book, Bullshit Jobs. The thing is, though—according to Graeber and his thoroughly researched, charmingly erudite collection of case studies—sanding a floor is not actually a bullshit job. You see, bullshit jobs occupy a very particular niche in contemporary capitalism’s vast and brackish Sargasso of corporate parasitism in which everything is owned by no one in particular. A bullshit job is very hard to explain to anyone, even oneself. A bullshit job yields no tangible result. A bullshit job creates a record of itself, but little else. We are surrounded by bullshit jobs. –JD

Fran Ross, Oreo (1974)

There’s no real way to describe this novel, because it is something that must be experienced first-hand—in fact, the less you know or expect going in, the better, so stop reading here, seriously. But if you must know more, this is a post-modern masterpiece by any measure, including menus, quizzes, notices, graphs, and invented languages, and it is about Blackness and Jewishness and female-ness and coming-of-age-ness, and it is both intellectually challenging and hysterical. I can’t believe it took me this long to read it. –ET

Mary McCarthy, The Group (1963)

When I started reading The Group, a friend told me it was like Girls in the 1930s. And though that description might turn some readers off, I found it both intriguing and apt. Both tell the stories of women in their twenties—women whose likability is of no consequence to their creators—fumbling their way through love, careers, and (in the case of The Group) New Deal America. The slices of women’s lives the novel presents are so precisely drawn that months later, I can still picture the apartments and maternity wards and offices the characters inhabited. Even better, critics at the time dismissed the book as a “lady-writer’s novel”—my favorite kind. –JG

John le Carré, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963)

Earlier this year, having swiped a 1970s paperback edition from my mother’s house, I finally got around to reading John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. Le Carré’s breakout novel, which established the author’s God-tier spycraft bona fides back in 1963, is a slim, masterfully calibrated tale of jaded agents, amoral geopolitical machinations, and the brutal realities of Cold War espionage—everything I’d been promised from the genre’s Ur-text, essentially. Fair warning: it’s bleak as all hell. That ending… Christ… –DS

Mary Gaitskill, Bad Behavior (1988)

Despite its cult classic status, my first encounter with Bad Behavior was just a month ago, and I’m still riding the high. The debut story collection that launched Gaitskill’s career, Bad Behavior is everything your smart friend who recommended it to you (thanks, Doug) likely says it is: grim and funny, told in sparse prose with precise detail, mapping the sexual desires, relationship-related calculations, and common degradations of women without moralizing. The book came out in 1988, but the thorny interiorities of Gaitskill’s protagonists feel contemporary. –WC

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Unconsoled (1995)

I’ve heard a lot of different opinions about The Unconsoled. Half of them are that it’s genius; half are that it’s unreadable. Obviously, I had to find out for myself. I found it to be a Kafkaesque shaggy dog story that shouldn’t, really, have been any good, and certainly shouldn’t have been compelling, based on what usually makes books compelling (actions having consequences, characters growing and changing, the rules of the universe making any sort of sense), and yet . . . I couldn’t stop reading it. All 535 pages. I don’t know, you guys. But I’m a fan. –ET

Anne Boyer, A Handbook of Disappointed Fate (2018)

I picked up Boyer’s book mostly because I couldn’t stop thinking about the title. Disappointment, fate, yes. The opening essay, “No,” is an exploration of the capacious political and aesthetic possibilities within refusal. And this trickles out into the rest of the book. My favorite just might be “Difficult Ways to Publish Poetry,” which lists husbandry to sewistry to reproduction as options. All very striking in the face of what Boyer calls a year in which “poetry had become abundant […] many believed that poems were worthless.” –SK

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

It turns out most of my favorite books in the world can be found on a high school English course’s syllabus. The Sun Also Rises shocked me in how much I loved it. Hemingway writes so sparsely you’d think it’d be easy to replicate, and yet he is the only one to do it: he gets to the core, says only what needs to be said. He speaks so simply and beautifully, so surely, whether about pouring a drink, going fishing, watching a bullfight, pouring another drink. The language is concise, the characters given away only through their conversations, moods shifting like weather. There are moments of startling brevity, drunken nights where no one says quite what they mean, and utter desolation, culminating in one of my favorite book-ending scenes: Jake and Brett in the back of a cab speaking, yet again, about how lovely their lives would be if only they could be together. If only, if only. –JH

Jean Kyoung Frazier, Pizza Girl (2020)

The protagonist of Jean Kyoung Frazier’s Pizza Girl is someone not quite like me, but a girl I used to be. Eighteen-year-old Jane, a pregnant pizza delivery girl, is anxious, lost, and endearingly flawed. Living in the suburbs of Los Angeles with her mother and her high school boyfriend, she’s also still grappling with the death of her alcoholic father. After meeting stay-at-home mom Jenny Hauser, Jane becomes obsessed with Jenny. She projects her fears and uncertainties about her future onto the older woman, using the escapism of fantasy to avoid taking control of the present. Frazier’s prose crackles with equal parts fevered hope and the nihilism of youth.

Is Jane entirely “likable”? Well, not really, but who says books can only center on likable women? What’s interesting about Jane and Jenny is their obvious discomfort with their societal roles and how they choose to rebel against these constraints. Although there’s something undeniably transactional about their newfound alliance, Jane and Jenny find common ground. Jane’s relationship with Jenny explores the pressures of motherhood and the disappointments of womanhood. By the end of the novel, Jane is not a radically different person but is ready to face herself and make something salvageable out of the wreckage. This singular coming-of-age tale is at once a tender excavation and heartbreaking revelation. –VW

Aimee Bender, Willful Creatures (2005)

Aimee Bender is one of my favorite short story writers, and this collection really cements her place in my heart. The premises are weird in a delightful way, as per usual. A man goes to a pet store and buys himself a little man. A woman has potato children. In one of the best stories, “Fruit and Words,” a not-bride finds herself running away from her life, hitting the road, and encountering a fruit stand run by a strange woman who also sells words made out of the thing they are describing (i.e. the word “nut” made of nuts, “blood” of blood). You know you’re reading an Aimee Bender story when you’re surprised at every level. Not only are the premises peculiar, but everything down to the last word choice is a twist (i.e. pity, described as something that “kept unbuckling in her heart”). Aimee Bender’s mind is an odd place, and we are lucky for this glimpse inside. –KY

Lara Feigel, Free Woman (2018)

“There were too many weddings that summer.” So begins Lara Feigel’s exploration of womanhood and freedom—sexual, political, intellectual, and otherwise—through the framework of Doris Lessing. I’m a sucker for a good bibliomemoir, this one included (and I knew next to nothing about Lessing before reading, lest you consider that a bar for entry). Not for nothing, Feigel writes some of the most moving descriptions of pregnancy loss that I’ve ever read; I also appreciated her musings on the fear of writing publicly about one’s private life. If those topics appeal to you, enjoy! –ES

Octavia Butler, Kindred (1979)

This year, I had the pleasure of reading Octavia Butler for the first time. Given Butler’s cultural stature, my expectations were high, but in a sort of nebulous way—beyond the acclaim, I didn’t actually know that much about her work. But Kindred blew my mind. If you’re reading this website, chances are high you’re familiar with Butler’s most (and soon to be adapted) work, but just in case: the book is told from the point of view of Dana, a Black writer in 1970s LA who gets pulled back in time to a plantation in antebellum Maryland. Kindred made me gasp and hold my breath perhaps in equal measure. Book publications may wildly over-use the word “urgent,” but I can think of no other word for this one. –JG

Grace Paley, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (1974)

It took a crazy amount of time for me to read Grace Paley’s slim short story collection Enormous Changes at the Last Minute; I could barely get through a single page without stopping, starting, throwing my hands in the air, giving up on ever writing anything myself, deciding to keep reading anyway. Such is the power of this author and the energy of her stories.

The collection, published in 1974, features a cast of people so fully real that they felt likely to emerge from the page into my apartment just in time to pick a fight, make some wisecrack, demand to know what I was doing, or cause a family scene. They live together, laugh, argue about politics, and cultivate the quiet desires and regrets that make up the inner world of a home. Paley’s writing is as filled with human insight and human frenzy as a city block, and the voices of her characters, engaged with the daily joys along with protests of the working class in one of the most economically stratified places on earth, are as relevant today as they ever have been. –CS

Katie Briggs, This Little Art (2017)

I was drawn to Briggs’s book mostly because of the shape of the essays on the page: largely small, square, and visually paralleling prose poems. This Little Art begins with Briggs’ experience of translating Roland Barthes’s lecture notes, and slowly unravels into questions of the pitfalls of translating, the anxieties and desires therein. It’s a complex terrain, writing out the threads of Helen Lowe Porter, Robinson Crusoe, and aerobics (to name a few) to examine the ways in which translation at times feels futile and at others necessary. In all its digressive magic, it’s an essay, but one that collapses into a liquid kind of lyricism. –SK

Simon Armitage, tr., Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (14th century, translated 2009)

This year, I re-read my favorite medieval poem in anticipation of the (very good) film adaptation, and let me tell you, it holds up. I knew it was going to hold up, since I loved it in an 8am lit class when I was a teenager, but still. Recommended for those who love weird language and dark forests. –ET

Kazuo Ishiguro, An Artist of the Floating World (1986)

Having now read five of my beloved Kazuo Ishiguro’s eight novels, I can (semi-confidently) announce that An Artist in the Floating World is my . . . third favorite. Lest that seem like faint praise, I should clarify that I was extremely taken by the tortured titular artist and his quiet-but-spiraling concerns about his actions in pre-WWII Japan/his reputation in post-WWII Japan. I just didn’t love him quite as much as I did the sad butler or the forgetful old couple (apologies to the doomed clones). There’s no shame in being beaten into bronze by those sorrowful icons, though. –DS

Helen DeWitt, The Last Samurai (2000)

Because my boyfriend and I are nerds, we decided to book club Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai this past year. At 482 pages, it’s a little intimidating, and we thought it best to start the journey together. We let the universe decide when we would start the novel; the day our local bookstore had two copies would be our lucky day. I began my write-up of this cult classic with this silly anecdote because it is very much a novel about chance (or fate) and an attempt to connect to something outside of yourself.

It follows Sibylla, a woman who finds herself a single mother after a one-night stand. She turns to a few high-brow theories of child-rearing for help and is met with astonishing results. Her boy Ludo turns out to be a charmingly precocious genius. He’s obsessed with The Iliad. He’s learning Japanese. There are even math problems laid out somewhere in this giant tome. Yes, Ludo seems to know everything—except who his father is. So begins his quest! (The boyfriend once referred to it as “the original Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close,” and that’s honestly a pretty good description.) It’s a gleefully experimental novel that could be confusing in lesser hands, but Helen DeWitt executes it masterfully. If you’re hankering to sink your teeth into something really great, I can’t recommend this book enough. Sibylla and Ludo are well worth your time. I think of them often. –KY

Nella Larsen, Passing (1929)

I have a lot of gaps in my classics reading, but I was very excited to watch Tessa Thompson and Ruth Negga in Passing this year, and I couldn’t bring myself to watch it without reading the original first (hashtag Smug Book Reader). I sat down and read it in one glorious afternoon; afterwards, I googled “Nella Larsen’s Passing should be the Great Gatsby of American literature,” certain this was not an original thought and someone had written this essay. (No luck, but I’m sure it’s still not an original thought.) Passing is everything that Gatsby acolytes want me to feel when reading Gatsby (and I just… don’t). Larsen’s sentences are stunning, the plights of Irene and Clare captivating, and Emily Bernard’s introduction shed light on why we only have two novels from Nella Larsen, a literary loss of the highest order. My loss for not reading sooner, but my first reading definitely won’t be the last. –ES

Milo de Angelis, Theme of Farewell and After-Poems (2013)

I received this book as a gift, and it quickly became one of the most important poetry collections in my life. Milo de Angelis chronicles his journey following the death of his wife, poet and writer Giovanna Sicari, in 2003, with quietly reflective lyric verse. This bilingual version from the University of Chicago Press features the original Italian along with a translation by Susan Stewart and Patrizio Ceccagnoli. –CS

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Talents (1998)

What can be said about Octavia Butler that hasn’t already been said? Prophet, visionary, genius—Butler is the truth. Parable of the Talents, originally published in 1998, is the sister novel to Parable of the Sower. In Talents, we continue to follow Lauren Olamina and years later, her daughter Ashe Vere, who seeks to uncover the truth about her birth mother. At the start of the novel, it’s 2032 and Lauren is 23. Her dream of communal living has come true. However, there is a new threat to the already fractured country: Texas Senator Andrew Steele Jarret. Jarret is a fascist who uses Christianity to justify his bloodthirst. His campaign slogan is “Make America great again.” (Remind you of anyone?)

Reading Talents is an immersive experience. Butler’s dystopia looks frighteningly like an inevitable final version of our modern world—zealous despots, devastating climate change, religious intolerance, extreme divides between the classes that have all but wiped out any semblance of the middle-class. And yet, despite the horrors, Butler’s narrative is not without hope. Humanity will never be completely doomed if there are people who selflessly use their talents to lift the world out of the darkness. –VW

Aaron Kunin, Cold Genius (2009)

I’m a fan of Aaron Kunin’s Oulipian limitations—the re- and re-written analysis of Love Three, the 200-item word bank and Maeterlinck & Pound source texts of The Sore Throat & Other Poems. Kunin’s collection Cold Genius (Fence Books, 2014) has a particularly destabilizing convention: he uses quotation marks to track every repeated word and phrase in each poem.

The poems’ content explores the knotty relation between feeling and language: language’s inadequacy to communicate feeling, language conjuring its own feeling. Other topics: Chiquita Banana, tickling, jokes, love and physical pain. (Not so surprising that each of Kunin’s tightly confined books has at least a few stanzas about the joys of being restrained.) The quotation marks spotlight Kunin’s signifiers, offering the reader an alternate rhythm, a new way of reading and questioning the “meaningful words” of Kunin’s own text. The last line: “’I’ once gave someone ‘a’ dictionary.” –WC

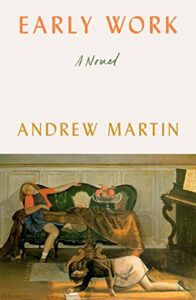

Andrew Martin, Early Work (2018)

The main emotion I felt reading Early Work was confusion as to why I hadn’t read it before. Why had no one pressed this perfect book into my hands before this year? I’m almost embarrassed to have it on this 2021 list, but if anyone out there also somehow missed the Andrew Martin boat: it’s not too late. It’s the correct combination of light and depth, humor and gravity. It feels like (forgive me) the work of a male Sally Rooney: a seamlessly written, conversational book of relationships and ambivalence and desire and wanting life to be bigger than it is. I finished it on a plane flight and put it down and wrote for hours about what I wanted and what I feared in life, which truly may be the highest compliment I can give to a novel, that it could crack me open in that rare, specific way. –JH

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.