Teddy Roosevelt Hated Baseball

It Was a Struggle to Even Get the President to Go to a Game

Father and all of us regarded baseball as a mollycoddle game. Tennis, football, lacrosse, boxing, polo, yes—they are violent, which appealed to us. But baseball? Father wouldn’t watch it, not even at Harvard.

–Alice Roosevelt Longworth

*

Today’s Washington Nationals may never win a World Series title, but they seem to have a knack for presidential history, at least as it pertains to their mascot race. During each home baseball game, the Nationals have a presidential mascot race after the top of the fourth inning. The Mt. Rushmore quartet—Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt—loop around the field to the delight of Nationals fans. It’s good, simple fun. “The only two rules we had,” said Josh Golden, the Nationals’ director of marketing, “were don’t fall down and Teddy doesn’t win.” And for the first 525 races (yes, 5-2-5), Theodore Roosevelt did not win. Ever. Payback, as they say, is a, well . . . it’s not fun.

Roosevelt really began solidifying his place in this baseball purgatory in 1906. During his fifth full year in the White House, his cold war on baseball could no longer be overlooked. The press picked up on the fact that Roosevelt ignored the World Series (PRESIDENT DECLINES. Will Not Be Able to Take in the World’s Series) and never attended Major League games in the District. “The fact is,” the Baltimore Sun wrote in 1906, “that Mr. Roosevelt is not greatly interested in the national game nor has he ever been.” Baseball’s leadership could have just let it go. Roosevelt’s time in the White House was dwindling; there would be a new president to win over in a couple of years. But no. Rather than minimizing Roosevelt’s slight, baseball’s leadership launched an all-out assault to win over Roosevelt. Oh yes, he will like us became the (unstated) rallying cry.

It seems clear now that baseball had hit its adolescence. The game was at once confident in its newfound strength and desperately insecure about where to sit in the cafeteria that was America’s Strenuous Life paradigm. “We first learned to admire Mr. Roosevelt while we were on the editorial staff of the Outing Magazine in the early ’80s,” wrote Henry Chadwick, the self-proclaimed “Father of Baseball,” in 1903. “‘We the people’ should feel happy, indeed, by reason of the fact that our President combines with his ‘strenuosity for the right’ and enlightened conscience and a large measure of brains.” Such statements by baseball leaders became commonplace. Chadwick, along with the editors of the Sporting Life (known as “The Paper that made Base Ball Popular”), sporting goods magnate Albert Spalding, and American League President Ban Johnson all did their parts to get Roosevelt on board with the National Pastime. Still, the president did not attend a game during his first term, despite the fact that the Senators’ ballpark sat just two miles from the White House.

“He had always been an admirer of the game, but on account of his poor eyesight had never been able to take an active part in the game.”

The realization that TR remained MIA from MLB launched baseball’s Great Roosevelt Chase. Baseball leaders set their sights on Roosevelt in earnest in 1906. The chase continued through 1907. It began with Ban. Ban Johnson, president of the American League, called at the White House in early April 1906. That Johnson could gain access to Roosevelt was a less an indication of Johnson’s standing than Roosevelt’s open-door policy toward visitors to the presidential mansion. Still, the two dignitaries sat down to talk. Johnson told reporters proudly that he and Roosevelt “had a very interesting talk of probably ten minutes’ duration.” Johnson wanted Roosevelt’s support, and what Johnson wanted he usually got. He was a ruthless business man, the veritable “Czar of Baseball.” Johnson had reveled in taking on the National League and poaching away its best players.

Johnson was so cold and unsympathetic when it came to business matters, that his contemporaries joked that he had probably been weaned on an icicle. Such emotionally detached tactics, however, didn’t really work with the president of the United States. So to the White House Johnson brought a gift. Perhaps he could woo Roosevelt to the ballpark. With as much ceremony as he could muster, Johnson presented Roosevelt with “a Golden Pass.” The pass entitled the president to complete access of the District’s American League stadium. He could attend any game at the stadium, which sat where Howard University’s hospital is today, and with any number of companions. The doors were always open, Johnson emphasized, to the president. If he wanted, Roosevelt could even “adjourn the Senate and both houses and take the whole bunch to the game.” Seriously, just come.

The golden pass was just what it sounded like—a pass laced with gold. According to Johnson’s suspiciously self-serving report, Roosevelt “expressed regret that he had never been able to play the game of baseball.” But it wasn’t for lack of affinity: “He had always been an admirer of the game, but on account of his poor eyesight had never been able to take an active part in the game.” The conversation, according to Johnson, ended with a promise. “The President assured Mr. Johnson that in [the] future he would attend many of the games played at the grounds in the capital.” The reporters of the Washington Post, perhaps knowing Roosevelt a bit better than their out-of-town competitors, took a pessimistic view of the effectiveness of the pass in changing Roosevelt’s behavior. While the Sporting News exuded hope, the Post remained skeptical.

The stakes were clear. Want President as Fan, read the Post’s headline covering the Johnson visit. “Washington Club aims to have Mr. Roosevelt attend Games.” But the District paper also acknowledged that Roosevelt had rather conspicuously avoided the game to this point in his presidency. This seemed unlikely to change. Still, representatives from the AL and the Washington Senators pulled out all the stops. “One of the most costly and artistic annual passes ever issued by a baseball organization has been made for presentation to the President of the United States,” the article made clear. “This pass, embossed in gold, is enclosed in a seal case, on the outside of which is a monogram of the President, ‘T.R.,’ in solid gold.” Who could resist such a flattering gift?

To baseball purists, Roosevelt’s Square Deal, which had become a “new National Phrase,” was essentially the “Love of Fair Play.”

Baseball assumed Roosevelt had been won over and would beat a path directly to the ballpark. So, prior to Opening Day of the 1906 season, the Washington Club constructed a “special box for the personal use of the President and his party” at American League Park. Just to be ready. Maybe baseball had the moral high ground in this pursuit. After all, Roosevelt in 1906 again agreed to serve as the Honorary President for the Olympic Games, this time of the American committee, since the ill-fated, off-year Olympic Games was held in Athens, Greece. Roosevelt provided a message of congratulations for the American Olympians, one that James Sullivan paraded around as an official endorsement. “The President again showed his deep interest in the success of the team,” Sullivan crowed. Why couldn’t baseball get a bit of this presidential affirmation? While getting Roosevelt to actually attend a game emerged as baseball’s Holy Grail, the effort anchored a broader plan meant to link the president to baseball.

An issue of the Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, which happened to feature a provocative essay on baseball’s origins (Was it possible the game was not uniquely American?), tried a Rough Rider-baseball connection. “Wellington said that ‘the battle of Waterloo was won on the cricket fields of England,’ and President Roosevelt is credited with a somewhat similar statement that ‘the battle of San Juan Hill was won on the base ball and foot ball fields of America.’”

The next year’s publication of the popular Guide shifted tactics slightly. What if baseball was actually best understood as an embodiment of Roosevelt’s “Square Deal?” The Square Deal was the phrase that Roosevelt had coopted to describe his domestic agenda. While broad, it included aspects of consumer protection and corporate regulation. “If there is one thing that I do desire to stand for,” Roosevelt explained, “it is for a square deal, for an attitude of kindly justice as between man and man, without regard to what any man’s creed or birthplace or social position may be.” What could be more square than a pitcher and batter facing off? Certainly the ball did not care about a man’s station in life. “When two contesting nines enter upon a match game of Base Ball, they do so with the implied understanding that the struggle between them is to be one in which their respective degrees of skill in handling the bat and ball are alone to be brought into play.” To baseball purists, Roosevelt’s Square Deal, which had become a “new National Phrase,” was essentially the “Love of Fair Play” that had always guided baseball’s development.

Alas, the 1906 season came and went without Roosevelt attending any baseball games, personalized AL pass or not. Undeterred, supporters of baseball tried again as the 1907 season dawned. Perhaps recognizing that a grassroots campaign might help, the Sporting Life worked to point out that Roosevelt was one of the few important people in Washington DC not interested in baseball. Even the stuffy Supreme Court got it. Chief Justice Harlan, of the Nation’s Highest Court, Plays Base Ball and makes a Home Run in His 74th Year, trumpeted one headline. “Far from distracting from the dignity of the distinguished incumbent of the Supreme Court seat, the ability of Harlan as a hitter will add to it. That home run is a human touch, a specimen of Americanism that will go far toward popularizing the venerable judge.” Then, just so its readers would not miss the point, the writer posed a rhetorical, shaming question. “How Theodore Roosevelt, who instinctively seems to know how to do the thing that pleases the people, came to overlook the diamond and its opportunities is a mystery.”

Baseball was on its knees now. There was no sense of shame when it came to chasing down a US president.

Baseball was on its knees now. There was no sense of shame when it came to chasing down a US president. Having given TR a pass that went unused in 1906, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues (NAPBBL), which became known as baseball’s minor leagues, decided to step up the pressure on Roosevelt significantly. Rather than just awarding the president a pass to one particular league, for a given season, the NAPBBL invited the president to attend baseball games forever. The pass presented to Roosevelt on May 16, 1907, at the White House transcended almost every conceivable baseball boundary.

The “President’s Pass” covered 36 leagues and 256 cities; it bestowed upon Roosevelt “life membership in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues, with the privilege of admission to all the games played by the clubs composing the association.” The size of a normal baseball ticket, this honorary pass was made of solid gold. The ticket itself drew press attention. The ticket “doubles in two on gold hinges to fold, so that it may be carried in the vest pocket.” The ticket had an engraved picture of the president and the date of presentation on its front. “The photograph of President Roosevelt is beautifully enameled on the fold. The rim is intertwined with delicate chase work. This remarkable card was engraved by Mr. Arthur L. Bradley . . . It is pronounced by all who have seen it to be a fine piece of artistic workmanship.”

As had been the case the year before, Roosevelt welcomed baseball’s leadership at the White House to present its self-serving gift. The president of the NAPBBL, P.T. Powers, led a small contingent of baseball lifers into Roosevelt’s office. Powers did not let his chance at an audience with the president of the United States go by without taking an aggressive swing at getting Roosevelt’s support. For a few minutes, Powers had the floor as Roosevelt listened. Then Powers introduced J.H. Farrell, secretary of the league, to make baseball’s case. “Mr. President,” Farrell began. “A nation is known by its sport, and that nation that fosters and encourages manly sport is the one that will produce manly men with rugged constitutions and perfect physical development. “The sport of this country, above and beyond all others is base ball. It is rightly called the national game, and its right to be so called is undisputed.” Roosevelt listened attentively; he knew how to give his visitors their moment in the White House. Farrell pushed on. “We all gain strength, courage and much moral growth from the national game.” Finally, Farrell moved toward his climax. “To its devotees all over this fair land from ocean to ocean there is nothing more gratifying than the fact that the present executive head of this great nation is an ardent champion of the national game.” Roosevelt was not an ardent champion of the game, of course, but Farrell was rolling by this point.

Baseball deserved Roosevelt’s support; after all this was a “game that nourishes no ‘molly coddles.’” To Farrell’s and the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues’ credit, the short speech ended with a flourish of honesty. Why had the group come? “We desire to make you one of us as much as we can,” Farrell said. “We desire to make you one of us as much as we can by tendering you a life membership card to any and all games of this, the largest Association ever organized in base ball history.” Roosevelt accepted the gift, and the speech, with his typical good graces. He did not make any promises, but he examined his new golden ticket closely. He “expressed his warm thanks” and remarked that baseball had particular potential because “men of middle age” could participate. Roosevelt also, according to the baseball men, “said he regarded Base Ball as the typical game for Americans.” These ranked as compliments, sort of.

Roosevelt never used his solid gold, National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues ticket. In fact, Roosevelt did not take in a single professional baseball game during his time as president.

_______________________________________

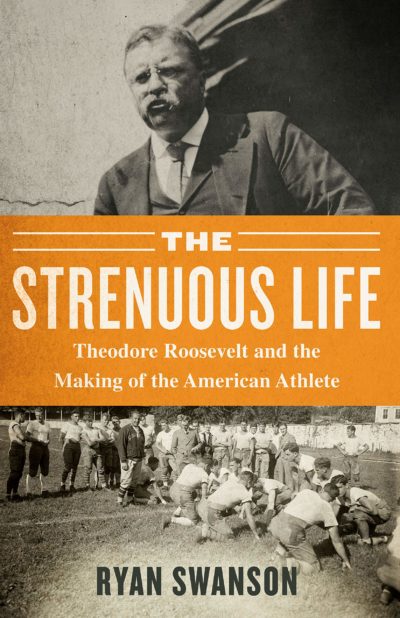

Excerpted from The Strenuous Life: Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete by Ryan Swanson. Copyright © 2019. Available from Diversion Books.

Ryan Swanson

Ryan Swanson is an Associate Professor of History at the University of New Mexico. He earned his Ph.D. in history from Georgetown in 2008 and has been studying and researching Theodore Roosevelt and his role in athletics in the United States for the past ten years. He is the author of When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation, and Dreams of a National Pastime, which won the 2015 Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) research award, and Separate Games: African American Sport Behind the Walls of Segregation, which received the North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) book prize in 2017.