Talking About the Pain and Anxiety of Menstruation

"I had known pain before, of course. But this was different."

One day in our early lives as women, everything changes. We start bleeding. The beginning of our menstrual cycle, our fecundity, renders us different. In an instant we’re no longer children. I was on a crazy golf course overlooking Cromer Pier when I experienced period pain for the first time. It was the summer holidays, and I’d started my period while away with my dad, brother, and sister just before my fourteenth birthday. I’d taken to wearing my hair all scraped back, and my abundant forehead was absorbing the North Norfolk sun with vigor.

As I stared between a pair of wooden clown lips to putt my ball between, my lower body rippled with new sensation. It was a pain that didn’t fit inside my body. My pelvis hung suspended, like a bowling ball, threatening to burst from between my legs. That classic British coastal breeze perfume, thick with sun-roasted kelp and old deep-fat-fryer oil, took the nausea that seemed to come with these sharp churns to another level. I had to sit down on the grass. I thought, This is crazy.

Girls talked about period pain at school. Some fainted in class or on the benches next to the netball courts because of it. One girl vomited all over her desk in a math class and started crying before being led to the nurse’s office, the teacher’s hand gently holding the small of her back. These girls gained noble status. Their syncopes were crowns of maturity. To myself and others who hadn’t yet “started,” they were kind of a different species because their bodies knew things ours didn’t. We used to ask each other how bad it could be, us nonstarters, because we all knew what a stomachache felt like. But for a stomachache to have girls falling on their backs and puking into their pencil cases seemed wild.

Until I felt it.

This new pain burned through my thighs. My legs were like pipe cleaners as a teenager. That holiday they were so tanned they looked wood-stained. The blonde hairs on them caught in the light like fiberglass, and sitting on the grass, I wondered if I should start shaving above the knee (Mum had always said not to) as others did at school rather than stopping at the cap. My thighs carried on burning. I explained to Dad that I didn’t feel well. He nodded and told me just to “sit quietly.” I was aware of the shift in his gaze toward me in a way that I absolutely did not have the language for. Only feeling.

Something set me apart from my younger sister. A vague sense of shame swam about me. A few days earlier, we’d been in a four-man tent in Southwold, and I’d been sat by the zipper feeling a peculiar nostalgia or longing that I couldn’t place. I told myself I was homesick, even though home wasn’t a particularly great place to be then. When we got to Cromer, I went to the toilet and found maturity in my knickers. An initial rush of excitement—I could go back to school and be part of the in crowd! The swooning girls!—gave way to a funny sadness. I had to leave the house immediately after telling Dad. It wasn’t quite embarrassment that made me leg it—he did his best to make it a non-thing, a mini-celebration, even—but in my core I felt uncomfortable. That whole holiday was one of heavy, wordless feelings.

I had known pain before, of course. But this was different; it had texture. Emotion.

I recall that afternoon on the golf course so clearly, I think, because the overwriting of what my body once knew as pain felt so significant at the time. The letters of the word, p, a, i, n, are symbols. Abstract. But there was a physiological process happening in my body and brain as they learned to accept this new state and its corresponding language. I began to embody the word differently. I had known pain before, of course—broken fingers, headaches, tonsillitis, bruises, scratches, and bite marks from fighting with my siblings. This was different; it had texture. Emotion. I looked down at the grass and thought, for a split second, that it would never stop. That the pain was time itself.

Dad gave me the keys to go back to the house and take some ibuprofen. I made catlike sobbing noises the whole way. Back at the house, I lay on the sofa waiting for them to kick in. No one had mobile phones yet, so I couldn’t relay my woes to any friends on WhatsApp. Anguished emojis were years and years away. It was so quiet in that moment, apart from the pitiful cawing of seagulls (Why do they always sound so desperate?) overhead. Strangely, though, it wasn’t lonely. The pain spoke to me. It told me my human fabric had changed. As evidence of the encoding that happened that day, now, on most occasions that I hear seagulls, I will have flash visions of lying on that sofa holding my young, tortured belly.

I’m in my thirties now, and ever since my first period, they’ve always been a slog. I’ve had my own swooning and vomiting episodes as cramps ripped through my body—not ever at school, but often in shopping centers. I learned to deal with what always used to seem to me like an excessive amount of blood, which came in a variety of colors and consistencies. As a teenager, when I was on (Why did we say that? Upon what did we stand and then step off again?), I’d be forever looking backward at myself in mirrors to check I hadn’t leaked through my clothes: a steadfast paranoia that, although lessened, still lingers today.

I have spent quite some time now trying to gain autonomy over the way my hormones seem to make my mind and body behave each month. At some point in the last five years, as part of my ongoing quest for peace of mind after a confidence-obliterating breakdown of sorts forced me finally to seek help for the anxiety that I had done my very best to conceal from everyone around me, including myself, for well over a decade, I started thinking about my menstrual health as part of my mental health. It was after a particularly bad period buildup one month, which felt like a week of crying from nowhere, overeating, and spending too many evenings lying on my front in an existential torpor, that I went to my GP. I asked her if this could really just be premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

The pain spoke to me. It told me my human fabric had changed.

Before the appointment I had somehow had the common sense to start making a monthly diary (read: a series of symbols Sharpied on the Cliff Richard calendar my best friend bought me) and realized that this way of being and feeling crept up on me every couple of weeks for a few days at a time. Notably, after my period, I’d have a week of feeling almost fantastic: productive, calm, resilient, porous to all the smell and color of life. I say almost because in the back of my mind, I’d be worrying about feeling hijacked again. So I asked the doctor what I could do about feeling as though my soul was fermenting every single month in a way I could not control. Since then I have tried all sorts of interventions in my quest for emotional stability.

More medications after several conversations with (almost exclusively male) gynecologists, who have made me feel either (a) madder or (b) ever so slightly less mad for a short amount of time. Acupuncture. Vitamin supplements. Diet changes. Broadly speaking, this precise, reliable emotional state I sought was, is, elusive at best and impossible at most realistic. I will revisit my hormonal quest in much more detail later on, but for now let’s just say that few of the interventions brought me relief. But in time, through addressing all the above with a new psychologist, and in the research I did for this book, I began to see things slightly differently and asked myself, “What am I seeking relief from?” Even if I could control certain symptoms of my premenstrual distress—low mood, for example—and a type of drug would be the answer, on a much deeper level, I wanted to know, “What is the question?”

One thing that became very clear on this journey was what I knew, didn’t know, or had forgotten about when it came to what was going on inside my body; my baby-making machinery—which, as yet, had made no babies, for the love of god—wouldn’t stop preparing for them each month. I wanted to explore what happens at each stage during the menstrual cycle in more detail because, through conversations I’ve had with many women, it seems that having greater awareness of what’s going on can be helpful in managing our moods but also in conceptualizing what a mood actually is: a state of being that is, by its nature, temporary. Whether that awareness comes from using a period-tracking app, starting a diary, doing online research, or reading books, the hope is that a greater level of acceptance of our fluctuations in mood and emotion can develop.

Some women out there seem able to embrace their pre-menstrual selves without much shame because there are lots of different ways of being a woman. As I am typing this, I am thinking of a brilliant line from an episode in season two of The Good Fight. Lawyer Diane Lockhart, actress Christine Baranski’s multilayered lead and also my hero, is accused by a young woman at the helm of a #MeToo-esque website called Assholes to Avoid of failing feminism for being part of the site’s takedown. “Women aren’t just one thing,” she snaps, “and you don’t get to determine what they are.”

No woman gets to determine what another woman is, wants, or desires.

______________________________________________

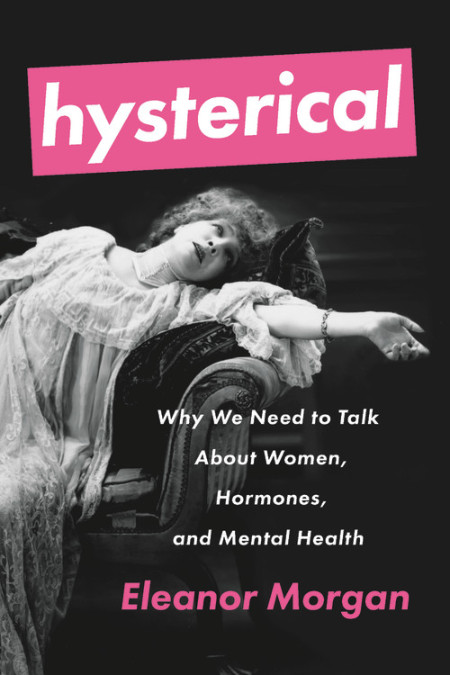

Adapted excerpt from Hysterical: Why We Need to Talk About Women, Hormones, and Mental Health by Eleanor Morgan. Copyright © 2019. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Eleanor Morgan

Eleanor Morgan is a journalist who has written and interviewed extensively for The Guardian, The Observer, The Times, The Independent, GQ, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Buzzfeed and The Believer. She worked as Senior Editor at VICE UK. Her first book, Anxiety for Beginners (not published in the US), served as a guide for those who live with anxiety disorders and those who live with it by proxy. Morgan is now studying to be a psychologist with women’s mind-body synergy as a predominant research interest. She lives in the UK.