Svetlana Alexievich on Why She Does What She Does

A Nobel Laureate at the Beginning of Her Career

For two years I was not so much meeting and writing as thinking. Reading. What will my book be about? Yet another book about war? What for? There have been a thousand wars—small and big, known and unknown. And still more has been written about them. But… it was men writing about men—that much was clear at once. Everything we know about war we know with “a man’s voice.” We are all captives of “men’s” notions and “men’s” sense of war. “Men’s” words. Women are silent. No one but me ever questioned my grandmother. My mother. Even those who were at the front say nothing. If they suddenly begin to remember, they don’t talk about the “women’s” war, but about the “men’s.” They tune in to the canon. And only at home or waxing tearful among their combat girlfriends do they begin to talk about their war, the war unknown to me. Not only to me, to all of us. More than once during my journalistic travels I witnessed, I was the only hearer of totally new texts. I was shaken as I had been in childhood. The monstrous grin of the mysterious shows through these stories… When women speak, they have nothing or almost nothing of what we are used to reading and hearing about: how certain people heroically killed other people and won. Or lost. What equipment there was and which generals. Women’s stories are different and about different things. “Women’s” war has its own colors, its own smells, its own lighting, and its own range of feelings. Its own words. There are no heroes and incredible feats, there are simply people who are busy doing inhumanly human things. And it is not only they (people!) who suffer, but the earth, the birds, the trees. All that lives on earth with us. They suffer without words, which is still more frightening.

But why? I asked myself more than once. Why, having stood up for and held their own place in a once absolutely male world, have women not stood up for their history? Their words and feelings? They did not believe themselves. A whole world is hidden from us. Their war remains unknown…

I want to write the history of that war. A women’s history.

*

After the first encounters…

Astonishment: these women’s military professions—medical assistant, sniper, machine-gunner, commander of an anti-aircraft gun, sapper—and now they are accountants, lab technicians, museum guides, teachers… Discrepancy of the roles—here and there. Their memories are as if not about themselves, but some other girls. Now they are surprised at themselves. Before my eyes history “humanizes” itself, becomes like ordinary life. Acquires a different lighting.

I’ve happened upon extraordinary storytellers. There are pages in their lives that can rival the best pages of the classics. The person sees herself so clearly from above—from heaven, and from below—from the ground. Before her is the whole path—up and down—from angel to beast. Remembering is not a passionate or dispassionate retelling of a reality that is no more, but a new birth of the past, when time goes in reverse. Above all it is creativity. As they narrate, people create, they “write” their life. Sometimes they also “write up” or “rewrite.” Here you have to be vigilant. On your guard. At the same time pain melts and destroys any falsehood. The temperature is too high! Simple people—nurses, cooks, laundresses—behave more sincerely, I became convinced of that… They, how shall I put it exactly, draw the words out of themselves and not from newspapers and books they have read—not from others. And only from their own sufferings and experiences. The feelings and language of educated people, strange as it may be, are often more subject to the working of time. Its general encrypting. They are infected by secondary knowledge. By myths. Often I have to go for a long time, by various roundabout ways, in order to hear a story of a “woman’s,” not a “man’s” war: not about how we retreated, how we advanced, at which sector of the front… It takes not one meeting, but many sessions. Like a persistent portrait painter.

I sit for a long time, sometimes a whole day, in an unknown house or apartment. We drink tea, try on the recently bought blouses, discuss hairstyles and recipes. Look at photos of the grandchildren together. And then… After a certain time, you never know when or why, suddenly comes this long-awaited moment, when the person departs from the canon—plaster and reinforced concrete, like our monuments—and goes on to herself. Into herself. Begins to remember not the war, but her youth. A piece of her life… I must seize that moment. Not miss it! But often, after a long day, filled with words, facts, tears, only one phrase remains in my memory (but what a phrase!): “I was so young when I left for the front, I even grew during the war.” I keep it in my notebook, although I have dozens of yards of tape in my tape recorder. Four or five cassettes…

What helps me? That we are used to living together. Communally. We are communal people. With us everything is in common—both happiness and tears. We know how to suffer and how to tell about our suffering. Suffering justifies our hard and ungainly life. For us pain is art. I must admit, women boldly set out on this path…

*

How do they receive me?

They call me “little girl,” “dear daughter,” “dear child.” Probably if I was of their generation they would behave differently with me. Calmly and as equals. Without joy and amazement, which are the gifts of the meeting between youth and age. It is a very important point, that then they were young and now, as they remember, they are old. They remember across their life—across forty years. They open their world to me cautiously, to spare me: “I got married right after the war. I hid behind my husband. Behind the humdrum, behind baby diapers. I wanted to hide. My mother also begged: ‘Be quiet! Be quiet!! Don’t tell.’ I fulfilled my duty to the Motherland, but it makes me sad that I was there. That I know about it… And you are very young. I feel sorry for you…” I often see how they sit and listen to themselves. To the sound of their own soul. They check it against the words. After long years a person understands that this was life, but now it’s time to resign yourself and get ready to go. You don’t want to, and it’s too bad to vanish just like that. Heedlessly. On the run. And when you look back you feel a wish not only to tell about your life, but also to fathom the mystery of life itself. To answer your own question: why did all this happen to me? You gaze at everything with a parting and slightly sorrowful look… Almost from the other side… No longer any need to deceive anyone or yourself. It’s already clear to you that without the thought of death it is impossible to make out anything in a human being. Its mystery hangs over everything.

War is an all too intimate experience. And as boundless as human life…

Once a woman (an aviatress) refused to meet with me. She explained on the phone: “I can’t… I don’t want to remember. I spent three years at the front… And for three years I didn’t feel myself a woman. My organism was dead. I had no periods, almost no woman’s desires. And I was beautiful… When my future husband proposed to me… that was already in Berlin, by the Reichstag… He said: ‘The war’s over. We’re still alive. We’re lucky. Let’s get married.’ I wanted to cry. To shout. To hit him! What do you mean, married? Now? In the midst of all this—married? In the midst of black soot and black bricks… Look at me… Look how I am! Begin by making me a woman: give me flowers, court me, say beautiful words. I want it so much! I wait for it! I almost hit him… He had one cheek burnt, purple, and I see: he understood everything, tears are running down that cheek. On the still fresh scars… And I myself can’t believe I’m saying to him: ‘Yes, I’ll marry you.’”

“Forgive me… I can’t…”

I understood her. But this was also a page or half a page of my future book.

Texts, texts. Texts everywhere. In city apartments and village cottages, in the streets and on the train… I listen… I turn more and more into a big ear, listening all the time to another person. I “read” voices.

*

A human being is greater than war…

Memory preserves precisely the moments of that greatness. A human being is guided by something stronger than history. I have to gain breadth—to write the truth about life and death in general, not only the truth about war. To ask Dostoevsky’s question: how much human being is in a human being, and how to protect this human being in oneself? Evil is unquestionably tempting. Evil is more artful than good. More attractive. As I delve more deeply into the boundless world of war, everything else becomes slightly faded, more ordinary than the ordinary. A grandiose and predatory world. Now I understand the solitude of the human being who comes back from there. As if from another planet or from the other world. This human being has a knowledge which others do not have, which can be obtained only there, close to death. When she tries to put something into words, she has a sense of catastrophe. She is struck dumb. She wants to tell, the others would like to understand, but they are all powerless.

They are always in a different space than the listener. They are surrounded by an invisible world. At least three persons participate in the conversation: the one who is talking now, the one that she was then, and myself. My goal first of all is to get at the truth of those years. Of those days. Without sham feelings. Just after the war this woman would have told of one war; after decades, of course, it changes somewhat, because she adds her whole life to this memory. Her whole self. How she lived those years, what she read, saw, whom she met. Finally, whether she is happy or unhappy. Do we talk by ourselves, or is someone else there? Family? If it’s friends—what sort? Friends from the front are one thing, all the rest are another. My documents are living beings; they change and fluctuate together with us; there is no end of things to be gotten out of them. Something new and necessary for us precisely now. This very moment. What are we looking for? Most often not great deeds and heroism, but small, human things, the most interesting and intimate for us. Well, what would I like most to know, for instance, from the life of ancient Greece? From the history of Sparta? I would like to read how people talked at home then and what they talked about. How they went to war. What words they spoke on the last day and the last night before parting with their loved ones. How they saw them off to war. How they awaited their return from war… Not heroes or generals, but ordinary young men…

History through the story told by an unnoticed witness and participant. Yes, that interests me, that I would like to make into literature. But the narrators are not only witnesses—least of all are they witnesses; they are actors and makers. It is impossible to go right up to reality. Between us and reality are our feelings. I understand that I am dealing with versions, that each person has her version, and it is from them, from their plurality and their intersections, that the image of the time and the people living in it is born. But I would not like it to be said of my book: her heroes are real, and no more than that. This is just history. Mere history.

I write not about war, but about human beings in a war. I write not the history of a war, but the history of feelings. I am a historian of feelings. On the one hand I examine specific human beings, living in a specific time and taking part in specific events, and on the other hand I have to discern the eternally human in them. The tremor of eternity. That which is in human beings at all times.

They say to me: well, memories are neither history nor literature. They’re simply life, full of rubbish and not tidied up by the hand of an artist. The raw material of talk, every day is filled with it. These bricks lie about everywhere. But bricks don’t make temple! But for me it is all different… It is precisely there, in the warm human voice, in the living reflection of the past, that the primordial joy is concealed and the insurmountable tragedy of life is laid bare. Its chaos and passion. Its uniqueness and inscrutability. Not yet subjected to any treatment. The originals.

I build temples out of our feelings… Out of our desires, our disappointments. Dreams. Out of that which was, but might slip away.

__________________________________

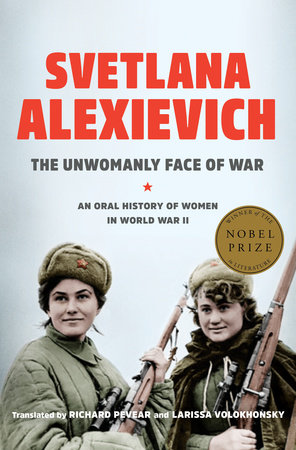

From The Unwomanly Face of War, by Svetlana Alexievich, courtesy Random House. Copyright 2017 by Svetlana Alexievich, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky.

Previous Article

Playlist for a Classic Novel:A Midsummer Night's Dream