Susan Griffin on Following the Sounds of Words

“If the sound of your words is true, your reader will be riveted if not enchanted.”

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Soon after my failed attempt at a war novel, I began to read passages out loud from books I liked. I had listened many times to my older sister, who was studying drama in high school, as she read passages from plays or poems out loud. So, as with practically everything she did, I followed her example. To whomever wGracould listen, I read stories by Hans Christian Andersen, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s stirring poem, “Renascence,” dialogues from Alice in Wonderland, and, though I never could finish the book, I loved to perform the first paragraph of A Tale of Two Cities.

Perhaps because of its notable symmetrical rhythm, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” or the dramatic list of contrasting circumstances, “It was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair,” I loved this paragraph and would read it over and over, even when I was alone in the back bedroom, staring out a window that looked over other houses, streets, a few palm trees, and a giant neon sign depicting red paint as it poured over a round earth, imagining as I read that I was creating a larger perspective on the urban scene below.

I did not know yet that with this practice I was training my ear to take in the music of language and, in the process, beginning to notice the music of the various phrases and sentences passing through my mind, bits and pieces, which even without any clear logic seemed to carry meaning. Over time I began to recognize these fragments as the seeds of something I might one day write.

When asked in an interview “how do stories begin for you?” one of the great storytellers of our time, Grace Paley, answered, “A lot of them begin with a sentence — they all begin with language.”

We think of language as conveying meaning. But here, I believe, Paley is talking about sound as well as sense. “Very often,” she goes on to say, “one sentence is absolutely resonant.”

In this way, literature is not, as many often suppose, abstract. Its medium is the human voice, a phenomenon every bit as concrete and sensual as oil paint or marble from Carrara. And though modern attitudes do not recognize the meaning inherent in the concrete world, the medium is never passive. As Michelangelo told us, the material from which he sculpted his masterpieces guided him. “I saw the angel in the marble,” he said, “and I carved until I set him free.”

Sound can dive beneath presupposition and assumptions, the world of clichés that has already bored you, to unlock the vital yet undiscovered and unspoken worlds that lie just beneath the surface of what has become habitual.

For this reason, it is important that you listen to the words you have written. If the sound of your words is true (in the sense of a true note or hitting the mark), your reader will be riveted if not enchanted. And, more crucial to this process of writing, which you have already begun by this time, you will be exhausted; put in a kind of trance, the way religious ceremonies from diverse cultures have done for centuries. Thus, even you, as you write, will be led by the sound of the words you have written toward a wisdom you did not know you had within you.

_________________________________

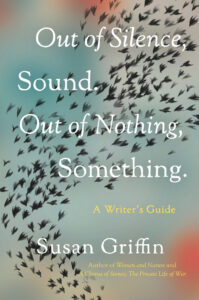

Excerpted from Out of Silence, Sound. Out of Nothing, Something., by Susan Griffin. (Counterpoint Press, 2023). Reprinted with permission from Counterpoint Press.

Susan Griffin

Susan Griffin has written over 22 books, including nonfiction, poetry, and plays. A Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and a New York Times Notable book. Woman and Nature, considered a classic of environmental writing, is credited for inspiring the ecofeminist movement. She and her work have been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Emmy, and the Fred Cody Award for Lifetime Achievement & Service, among other honors. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.