Suffering Under the Speaker: On Louise Glück, Garth Greenwell, and Vocal Duality

D.S. Waldman Considers His Own Poetic Voice Alongside Those of His Mentors and Peers

Two or three times a month, I receive a voicemail from some unfamiliar number in Kentucky. Beneath the number, my phone screen lists the county of origin. McCracken County. Danville. Pikeville. Lexington. And recently, a town or county I hadn’t heard of—Jackson. Never is anyone trying, actually, to reach me; some are the familiar spam calls, the scammer somehow copying my area code, I imagine to better the odds of me answering, but a lot are real people who simply have the wrong number.

I don’t answer, of course, but I welcome their voicemails. I listen to all of them. Having grown up, myself, in rural Kentucky, I find in these messages something akin to music—the accents often thick, sometimes indecipherable, some vowels elongated, some completely swallowed or cut off, the r’s famously steep. And it isn’t just the accent; there is magic, also, in the idioms.

Recently, I got a message from someone’s grandmother. She’d self-identified as Mawmaw, which is what I, too, called my grandmother.

I’m just driving out old Paris Pike, she said, and I saw your old house—so she decided to call.

That phrase, “driving out,” used this way, means something slightly different than, say, “driving to”—I’m driving to Lake Cumberland—and it’s different than “driving along”—I was driving along the Kentucky River. “Driving out” is paired usually with a road name. One might drive out 64W toward Lawrenceburg, or like Mawmaw, they might be driving out old Paris Pike when they encounter a familiar landmark, conjuring a memory. It’s a locution particular to rural America, places like Kentucky, where many people grew up in the country, but now live in town, in Lexington or Frankfurt or Louisville. To say I was driving out old Paris Pike indicates she was taking old Paris Pike out of town, into the country—horse country, tobacco country, whatever type of farm her family might have once tended. Nostalgia is inherent to this way of saying. She was driving into the past.

It feels apt that my time with Louise ended this way: unfinished, my issue of voice unresolved, the solution implied somewhere in her vast silence.

Maybe, then, it’s less music that I experience in these voicemails, these accents, these idioms, than it is Poetry.

*

When I began working with Louise Glück at Stanford in January 2023, she was quick to identify a strangeness in my poems. I’d brought a sheaf of new work to the back garden of the house she rented in North Berkeley.

I think your poems suffer under the speaker, she told me, Or really, I think you have two speakers.

She liked the poems written with what she called a “lucid intelligence”—poems set in museums, responding to contemporary art, poems interlacing theory and the quotidian, my romantic relationships. But she was less impressed with my Kentucky poems, which featured, for example, my brother and I “packing lips” in back of his truck, or our father, in an angry fit, described as “on the muscle,” or a reference to “hot browns,” a classic, heart-straining Kentucky breakfast dish. Louise didn’t know what these phrases referred to—and not in a good way.

Packing lips, for the uninitiated, refers to dipping tobacco, packing a pinch into one’s lower lip. And “on the muscle” is, in its origins, a horse terminology used to describe especially reactive, jumpy, or sometimes aggressive horses; one can imagine how the term might be transposed onto a certain type of person.

It can be fruitful to play with vernacular, Louise explained, but the two voices—the museum voice, the country voice—were too distinct. It wasn’t believable that they were the same speaker. They needed to be integrated.

*

My siblings and I were raised on a horse farm on the southern edge of Fayette County, maybe a mile from our neighbor’s house, and several miles from the next house beyond that. We lived outside the range of Fayette County school buses, so our mother drove us in to school every day. I don’t even know how far the nearest library might’ve been from our home.

I grew up in and around a language steeped in the agriculture of the place, the language of horses and tobacco and bourbon—my first drink, when I was thirteen, was a swig of Bulleit bourbon from a friend’s dad’s flask. It’s an English littered with many colorful expressions: August in Kentucky, for instance, is “hotter than a goats butt in a pepper patch;” when I first started working, as a summer gig on a family friend’s farm, I “didn’t know my ass from a hole in the ground.” These little flourishes, funny and demonstrative, represent a type of cleverness that is often valued over the traditional eloquence of learned grammar and vocabulary. In fact, even in school, eloquence can sometimes be seen as immodest, tricky, a way of showing off or trying to “pull the wool over someone’s eyes,” trying to make another person feel small.

I grew up with an accent. And though my parents were sticklers for grammar—they’d each, at different points in their lives, lived in the North, in Detroit, New York, Toronto, so had maybe gleaned the value of “speaking well”—I still, at school or with friends, preferred to speak in the vernacular and voice of the place. It wasn’t “How are you?” but rather, “Ha’ you?” Not “Don’t” but “Don’.” I didn’t ask “Where?” I asked, “Where at?”

When I was fifteen, though, through a series of extraordinary and fortunate circumstances, I earned the opportunity to finish high school at a fancy boarding school in California. There, I was in class with the children of tech moguls and famous actors and state Supreme Court justices, the children of college professors and editors at Rolling Stone. My accent and ways of saying signaled something different there, something other than modesty. I was put in remedial math. My essay on Hamlet was described by the teacher as “elementary.” I disappointed the small student Republican group when, early on, they approached me about attending their Tuesday night meetings. Even in contemporary political and intellectual discourse, there remains an attachment to a particular stupid southern conservatism, the ideocratic confederacy.

I learned quickly to integrate my parents’ household lessons in “speaking well.” I dropped the accent, put the “t” back onto the ends of contractions. I asked, “Where is the college counseling office?” leaving off the “at.” And by the time I got to college—another fancy little school, this one in New England—when I told people I was from Kentucky, they asked, Where’s your accent?

I do let myself drop back into the old accent and colloquialisms, when I’m at home in Brooklyn with my partner or when I’m back visiting my folks in Kentucky. I don’t drink anymore, but when I did, this John Fogerty infused persona would come out and, to the confusion and delight of friends, take over for an evening, becoming increasingly unintelligible as the night went on.

So, when Louise, that morning in Berkeley, called for an integration of my two speakers, my two voices, she was asking me, probably knowingly, to stitch together those two disparate versions of myself—the Art History major, matcha drinking poet, and the bumpkin dipping Copenhagen long-cut, listening to “Down on the Corner,” leaning into someone’s unbuckled truck bed.

Another trusted reader encouraged this integration, too: I don’t care about another white guy in a museum, he said, but a hick in a museum, that’s interesting. He too had grown up in the country, in central California.

*

Maybe it’s dramatic, speaking of my conundrum in these terms—integrating my split selves, my detached voices. The idea of code switching is well worn, speaking one way at home, and speaking another way in a professional or institutional environment. And I resist applying the term to the little poem problem Louise pointed out to me; if one code switches to protect oneself and preserve their perceived viability in the workplace, then it feels off, dramatic, maybe appropriative, to apply the term to me and my creative problem. Mine seems more an issue of voice, of the indispensable self we endeavor toward on the page.

While working with Louise, I also read and re-read several of her books—a sort of split education, learning at once from Louise Glück the (scrupulous) reader and critic, and Louise Glück the poet. I was reading with an eye for a dualness of voice, a seamless high-low register, something I could maybe learn from and strive for in my own poems. People speak of Louise’s austerity on the page, austerity and piercing clarity, and I do read that in her work; but the poems and moments to which I’m most drawn do, I think, involve a second voice, or at least a second tone, a voice that looms restrained like an underwater shadow, then in a single lyric flourish, pierces or breaches the surface. It’s an effect she herself describes in her very famous poem “The Wild Iris,” in a breathtaking, almost arspoetical moment: from the center of my life came a great fountain, deep blue shadows on azure seawater.

From the center of the poem—if we read these lines in terms of the poet’s duality, their second voice—comes a separate, searing voice, rising maybe from some deeper, truer place inside the speaker.

Among my favorite of Louise’s poems comes from that same collection, The Wild Iris, her poem “Vespers,” one of ten poems in the book with that title. I admire in particular, in a poem spoken directly to God, the lines in which all decorum falls away—fear of God falls away—and our speaker, whose tomato plants have died from blight, speaks from a place of unvarnished disgruntlement.

The poem begins in a slightly elevated, formal register, the way the reader might expect someone to speak to God:

In your extended absence, you permit me use of earth…

But almost immediately, the snark comes through:

…anticipating

some return on investment.

This is a brazen way to speak to or about God, as though they were a hedge fund manager. And we see this brazenness almost evolve or swell down the page:

I think I should not be encouraged to grow tomatoes.

—the measured and less emotionally–determined voice, pious, self-doubting. But then, as in an increasingly heated exchange or argument, that unvarnished and less restrained voice breaks through, can’t keep itself from breaking through:

…Or, if I am, you should withhold

the heavy rains, the cold nights that come so often here…

This is on you, the speaker tells God; you control the weather, and you killed my tomato plants. And this touches what seems the central tension of the poem, that God doesn’t have to live with and experience the repercussions of their choices and actions; the speaker does. We do. And it’s the speaker’s ire over this injustice (I doubt / you have a heart, in our understanding of / that term) that seems to propels this second, righteously indignant voice that, at poem’s end, after naming several quotidian heartaches endemic to the human condition (you may not know / how much terror we bear) proclaims plainly and directly, defiantly:

I am responsible for these vines.

I remember feeling confused at this realization, that Louise herself pretty consistently wrote poems with a sort of bivocality—confused and maybe a little frustrated. What was different about my voices, my dualities? How was I mis-applying them? Was Louise the teacher contradicting Louise the poet? I concluded that the vocal two-ness I read in “Vespers,” as well as in other of Louise’s poems, might not lineup squarely with the duality that worries my own poems, hers being less a duality of vernacular—of colloquial speech and affect—than of tone.

Reading “Vespers” and other great poems of hers, like “Night Song” and “October,” I began to think of voice as a sort of fabric: in “Vespers,” we have the vaguely formal, restrained voice that establishes a baseline for the poem, for the relationship between the speaker and the “you,” and we have the more charged, lyric voice that, here and there, accents the poem and, in those moments when the speaker’s emotions can no longer be fully contained, inflects the poem with the underlying feeling of it all: angst, frustration, righteous indignation. Voice, I mean to say, can set a pattern for the poem—and when the poem calls for tension or contrast, a shift in voice can break the established pattern, opening the poem to that lyric energy we experience when Louise basically calls God a finance guy, or in that astonishing line at the end of “Night Song”:

You’ll get what you want. You’ll get your oblivion.

*

I was part of Louise’s last cohort of students at Stanford. We worked together from January through May, at which point she returned to Vermont, her longtime home where she spent half the year. And when we all got the call that September, when I learned of Louise’s passing, I felt the seismic shift I guess occurs when a legend dies. The comfort of knowing there is time-worn brilliance and ballast and beauty in the world, among us, gave way to the worn truths of death and art and one’s work as monument to their life, their voice. I had a lot, still, I wanted to learn from Louise.

She spoke often—publicly, privately, in her prose—of her affinity for ellipsis, for the unsaid, eloquent and deliberate silence. In her essay “Disruption, Hesitation, Silence,” she writes, The unsaid, for me, exerts great power: often I wish an entire poem could be made in this vocabulary. She cites the power of ruins, of visual art either damaged or incomplete, a show she saw that included in-progress drawings by Holbein. They haunt, she writes, because they are not whole, though wholeness is implied: another time, a world in which they were whole, or were to have been whole, is implied. And so sometimes, in retrospect, it feels apt that my time with Louise ended this way: unfinished, my issue of voice unresolved, the solution implied somewhere in her vast silence.

Maybe a year later, while revising my first book of poems, I had the good fortune of reading a book that maybe, in some way, lent a sense of closure to my conundrum. I had decided, at the behest of that friend from Central California, to set my two voices side-by-side in the manuscript, a poem about my brother’s smoky Carhartt jacket situated next to a poem that cites Sontag, a poem featuring a beer cheeseburger next to a poem moving through a gallery of Alexander Calder mobiles. But I felt a lingering skepticism toward the endeavor—a skepticism, in retrospect, probably rooted in what I perceived as lack of precedent, of a lineage or tradition I could write into or alongside. The Kentucky poets I was aware of—Wendell Berry, Frank X. Walker, Etheridge Knight—all wrote with distinct voices, but not distinctly split voices (…the day upholds / carved orange lilies in a calm / dreamers no longer dream but know). So it felt serendipitous to encounter Garth Greenwell’s Small Rain as I revised my manuscript toward its finished book-form.

Small Rain is a novel, yes, but Greenwell is a trained poet, and anyway I think of Poetry as a current or energy that pulses through many forms of writing, forms of art. I learn a lot about poems from good novels.

I’d known Greenwell grew up in Kentucky, just an hour or so from the farm where my family lived, and I’d read and loved Cleanness, but what I loved in that book had more to do with Greenwell’s stylish and smart prose, his sensitivity and erudition: “There were hundreds of them,” he writes in Cleanness, describing a basement full of a street vendor’s paintings, “enough for a life’s work, for several lives. It was a kind of trash heap, I thought, or might as well be; they would just sit there, gathering dust and mold, they would never be looked at again. They were buried here, along with the hours and days they had taken, the effort.” Passages like these resonated with my own learned, East-Coast-educated, art-interested self.

The autofictional narrator of Small Rain is an educated poet who’s spent years of their adult life teaching literature in Bulgaria. He has returned to the States, has settled with his partner in middle America, Iowa, has bought a house and, though a little reluctantly, built a life. The narrator offers some of the familiar flourishes of erudition I loved in Greenwell’s earlier work—references to Walter Benjamin and Kant and Milton, an especially brilliant passage in which the narrator, laid up on pain meds in the hospital bed where he spends most of the novel, thinks intimately with the reader, intimately and insightfully, through the great George Oppen poem “Stranger’s Child,” scaling up from the poem’s, and generally Oppen’s, opacity and difficulty, to Oppen’s Communist politics and how they manifest in the poem, his “career-long worrying over the relationship between the one and the many,” and eventually relating “Stranger’s s Child” to Keats’s canonical poem “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” from which he extrapolates “a whole theory of civilization.” It’s probably my favorite part of the book; it reads like lively, world-class criticism. And I think part of what allows it to work, or maybe why it resonates with my own sensibilities, is that the erudition exists next to and in relationship with what seems the novel’s Middle-Americanness, its rurality.

Maybe in the end I did more or less what Louise had in mind for my poems—to not necessarily integrate the voices on the page, but to develop a more complete awareness of their context.

The novel features places and geographies and weather I grew up with: Louisville and Cincinnati and Sonora; long childhood drives from one small place to another, over undulant bluegrass hills, endless fields of soy beans and corn and cattle and horses; a distinctly midwestern storm called a Derecho, which we didn’t really see in central Kentucky—it was summer tornadoes for us, one of which swept through our yard when I was a kid, blowing through the fence, uprooting our tetherball pole—but we heard of Derechos from friends and family in bordering states. And I know very well the instinct Greenwell describes, when one of these storms arrives with its frightening and awe-inspiring skies, when the weather alerts tell you to seek shelter in the basement, to defy that “animal impulse to burrow or hide” and stand outside until the last moment, to witness the sheer force and thrill of intense storms.

Next to the particularities of place—the Midwest, the South—or enmeshed with it, are the particularities of language, of idiom, and ways of saying. Greenwell doesn’t overdo it here, which I appreciate; it would be easy, facile, to write caricatures of the country bumpkin, the hick, someone all the time saying y’all and Mama and spitting into a tin bucket on the porch. And though I do say y’all, and though I dipped tobacco for a couple years in high school and college, I’m drawn to Greenwell’s more subtle, more tasteful applications of rural linguistics. “Eat your heart out,” a woman yells after her dog who, in a standoff with its owner, goes and dives into a pit of mud. Or the phrase “This here,” as used by a contractor working on the narrator’s house, pointing to a faulty column: “This here is a safety issue.” Or how, in that same scene, when the contractor is confronted by the narrator over shoddy work on the house, it takes so little to trigger a rage response: “Not today,” he says, almost yells, after telling the narrator to shut up, “You are not making me feel small today.” Few things are less tolerable to a southern conservative man—the contractor’s truck is mounted with a gun rack and emblazoned on the sides with a large American flag—than being made to feel small, especially by a liberal intellectual.

Masculinity and conflict, for Greenwell, seem opportunities for rurality to most obviously manifest. When thinking back to this conflict with the contractor, the narrator recalls the phrase, “How dare you in my house”—something his father would say, and specifically said once to the narrator’s brother, “before he struck him full in the face.” All of it, the emphasis on one’s home and home ownership, the phrase “full in the face,” the striking of one’s own son, it all accents the text—again, through subtle applications of vernacular and speech—with a rural masculinity I recognize and intimately know, and which, at least to my reading, serves as a sort of second, occasional voice against which Greenwell’s vividness, erudition, and sensitivity vibrate.

I’m not suggesting the erudition in Small Rain exists despite the speaker’s rural American origins, though that is no doubt the easy impulse; I mean more that Greenwell’s velvet prose becomes maybe more interesting, develops a political context, because his personal geography is allowed, sometimes, into the language, because the second voice is allowed onto the page. I’m also not necessarily implying that reading Small Rain—and in particular, reading Small Rain while holding the conundrum incited by my work with Louise—provided a revision strategy that helped me finish and polish my poetry collection. But I do think Greenwell’s novel offered something I’d been missing, even after working with and reading Louise: a sense of lineage, of creative and literary fellowship. It helped me, maybe, to stop worrying so much about a unified or fully integrated voice, to stop smoothing what I perceived the rough edge between my two voices.

*

Part of me wants to say that Small Rain gave me the courage to disagree with Louise Glück, to reject the advice of a Nobel Laureate, American Poet Laureate, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, etc. I recently spoke about this impulse with another, older, former student of Louise, a poet who worked with her for four years at Yale; they said that might have been the last great gift Louise gave them: the confidence to disagree, now and then, with her suggestions: I get the sense she wanted that, this poet told me, she wanted me to know myself, and my poems, well enough to reject her advice.

It seems a rite of passage for those who worked with her, to achieve a state of sufficient self-knowledge, sufficient confidence, to feel aesthetically sturdy enough to defy the advice of our great teacher. But that doesn’t feel wholly true to my experience. I do know my poems’ speaker better now than I did then—a speaker who, in one poem, writes of “the homesick lyricism” in Keith Jarrett’s famous Köln Concert, and in the next poem, reminisces about WoFo Reserve and hot browns. But was this not the result of an exploration Louise herself incited? An exploration into her work, her own duality? I wonder too whether, when reading Small Rain, I would’ve been so attuned to Greenwell’s shifting registers, his splitness across erudition and rurality, if it hadn’t been for Louise’s suggestion to “integrate.” I don’t know. My mind goes back to that sentence she wrote: They haunt because they are not whole, though wholeness is implied: another time, a world in which they were whole, or were to have been whole, is implied. Maybe there is room, in integration, for absence. Messiness. Ruin. Maybe in the end I did more or less what Louise had in mind for my poems—to not necessarily integrate the voices on the page, but to develop a more complete awareness of their context, to conjure a world, a time, in which they were whole.

__________________________________

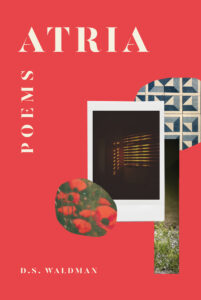

Atria by D.S. Waldman is available from Liveright Publishing Corporation, an imprint of W.W. Norton & Company.

D.S. Waldman

D.S. Waldman’s poems have appeared in The Atlantic, Boston Review, Kenyon Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, and ZYZZYVA, among other publications. A 2022–2024 Wallace Stegner Fellow, he teaches at Brooklyn Poets and Poets House. He lives in Brooklyn.