Stray Thoughts on Kafka, Loneliness, and Clothing-Optional Retreats

Peter Orner Wanders from Prague to the Red Woods

I.

Out the Window

Whoever leads a solitary life and yet now and then feels the need for some kind of contact . . .

–Franz Kafka, “The Street Window”

We lived in Prague that year: 1999. The place was crawling with Americans as clueless as we were. Woo-hoo, what iron curtain? The weather and the wet streets were romantically gloomy. Rent was cheap. We didn’t need much to stay alive. We began to talk about beer like scholars. And there were the antikvariats, the used bookstores. These dusty nirvanas were in every neighborhood, and there was always a shelf full of books in English. They sold for nothing. Many of them dated from the war. I bought a first-edition Virginia Woolf for fifteen crowns. The storeowners had contempt for any book that wasn’t in Czech. Why would anybody want to read a book that’s not in Czech? Every day I brought home another pile of books. We worshipped Václav Havel (and often staked him out at the Café Slavia) and read a lot of Milan Kundera. Communism sounded fun as told by Kundera, at least sexually. What’s a little repression in a utopia where everybody is sleeping with everybody? And the Czechs tolerated us—for a while, anyway. I got a job teaching Anglo and American law at Charles University. A few years earlier, I’d graduated from law school. Though it made my mother proud, the degree has never come in very handy except this one time when I was living in Prague with the woman who would become my wife. M (she’s asked me not to use her name) was making a film about what happened to the Gypsies after the fall of communism. There was better sex back then, and also, apparently, less (overt) racism. After the wall came down, so did the inhibition of many Czechs to express their dislike of people who they didn’t think were European. And the Roma, who’d lived among them for centuries, had never been considered European. It was as though people thought they’d arrived three days ago to steal everybody’s purses.

* * * *

The Law Faculty building at Charles University was—is—a vast hulk of a structure that squats on the bank of the Vltava River. Everything about the place is unnecessarily huge, the height of the ceilings, the doors, especially the doors. I’d never seen such needlessly enormous doors. You had to yank them open with two hands. Franz Kafka studied at the Law Faculty and graduated in 1906. I was sure the place hadn’t been renovated since. It wasn’t hard for me to imagine him wandering those halls not built to human scale.

I had a lot of time to wander myself. The job turned out to be not very taxing. Having slogged through law school, I knew a little something about American law, but in the beginning, in any case, I didn’t know what “Anglo” law even meant. WASPY? I was paid something like forty cents an hour, but again, it was enough to live on. Showing up to teach seemed optional. All the other professors had other day jobs. Capitalism was beginning to roar. But the Law Faculty was still mired in the old days. Sometimes I had five or six students; other times it was just me and this one guy named Jan. Jan wasn’t interested in Anglo or American law. He had a cousin who lived in East Lansing and wanted to practice his English without having to pay a private tutor.

This is nothing new. A lot of people pass through Prague and dream up some dopey kinship with Kafka, but I took the fact that not only was everything I did irrelevant and completely ineffectual, I was also serving time in the very same building where he, too, once toiled. I thought: I am as lost here on the face of the earth as he was.

After about a year and a half, the film finished, M and I left Prague and moved to Cincinnati. Why? I’m still not sure. But doesn’t everybody, at some point or another, move to their own private Cincinnati? After Cincinnati, we fled to California. Eventually, years later, we got married. Then everything fell apart. Doesn’t everything always fall apart in California?

* * * *

What follows is an aside, the reasons for which I hope will become clearer in a moment. Cut to that time not long after my marriage collapsed. I found myself lonely, bewildered, and, above all, exhausted. So I decided that what I really needed was a weekend at what people used to call a nudist colony but are now, in California, called clothing-optional retreats. If there is an almighty, omnipotent God, even He wouldn’t have known what the hell I was thinking. Though I told myself all I wanted to do was to be alone for a while, I must have been hoping to meet someone. Why else would I have gone to a nudist colony? The minute I arrived at the place (which has since burned to the ground) I knew the whole mission, whatever my motivation, was turning out to be one of my more harebrained ideas. The less people were wearing, the more shell-shocked I generally became. After the long drive and being stuck in that place for at least a night, and needing, right away, to get away from all that competitively exposed flesh (only in America could clothing optional turn into one-upmanship), I hightailed it, fully clothed, up to the top of a mountain, where I found a thatched hut with two yoga mats side by romantic side. The hut was new, but built to look weathered and authentic. Good a place as any. I decided to hunker down on a yoga mat. I stretched out on the mat and did a few moves I thought resembled yoga before cursing myself for not bringing a book up here. Or at least some drugs. Or a shotgun. I stared up at the roof of my hut. I tried to will a sense of quietude amid the redwoods. I sat cross-legged and tried to imitate meditation. That didn’t work, either. Too much peace makes me nervous. I must have been up there for at least an hour, staring at the thatch, ruminating on the multiplying effects of failure, when I was joined by a chatty, bearded guy wearing nothing but hiking boots and a loose thong.

Excuse me, bro, but what’s with all the threads?

Little chilly, that’s all. Must be the altitude.

You want to process this? Clothes are a construct, a prison. You unhappy in your own skin? Is that it, bro? Why deny the gift?

That’s it, exactly. Unhappy but happy. Unhappily happy?

So yeah, as much as I wanted to bludgeon the guy with my yoga mat, I was also grateful to him, because as much as I’d told myself I wanted it, needed it, solitude is not only scary, it’s work. As long as this thonged nudist was there to loathe, I didn’t have to be with myself. Which was becoming draining. I guess what I’m getting at is that true loneliness is a rare and difficult thing. We want it. We don’t want it at all.

Maybe it’s always been this way. Here’s an utterly unprovable theory I’ve been developing over the past couple of hours concerning Franz Kafka, after reading haphazard bits of his diary. He often craved it, but the reality is that the man wasn’t lonely at all. His social life was demanding and often extraordinarily busy. I’m lucky if I get invited to three parties a year, and the last one I truly enjoyed was a fundraiser for Obama back in 2008. This was only a few months after my foray into the world of clothing optional. There, at the house of a young, indescribably rich couple, I met the mother of my daughter. Actually, we’d met before, but she hadn’t returned my emails. She’s a novelist, but that night was a volunteer bartender and as liberal with the vodka as she is in her politics. I hovered by the bar and downed vodka tonics like a hero for Obama. Yes, we can. Sí, se puede. Somehow, together, we wobbled back to her apartment on Precita Park. Later, not that same night, we created a child. This took us both by surprise, although biologically it shouldn’t have. Biologically it was perfectly logical. We all know how this goes, but it still amazes me: together we created a big-eyed kid. In between, there was love and a fat, lazy dog.

But Kafka? We’re talking about a guy who was out at the Café Louvre yukking it up with Max Brod and his other law school buddies all the time. He often read his stories out loud to the howling laughter of his friends. Kafka was a serial fiancé who never married. He was a man who ran to people as obsessively as he ran away from them. My thought (it is now late dusk, the kitchen has changed colors, and I haven’t turned on the light yet) is that Kafka wrote so much about loneliness because he could never make up his mind whether he wanted it or not. In his diary he writes:

One can never be alone enough when one writes, why even night is not night enough.

And:

I have no family feeling and visitors make me almost feel as though I were being maliciously attacked. Being alone has a power over me that never fails.

But there’s also:

I passed by the brothel as though past the house of a beloved.

And:

It seems so dreadful to be a bachelor, to become an old man struggling to keep one’s dignity while begging for an invitation whenever one wants to spend an evening in company.

We are the sum of our contradictions. How could it be otherwise? Still, this fundamental and unanswerable and lingering question: Alone or with other people?

Many of Kafka’s stories involve a struggle between a craving for loneliness and a terror of it. See “The Judgment,” written in a single feverish night. Why the hullabaloo over an imaginary Russian friend? Either invite him to the wedding or don’t . . .

But there’s one very short piece that unfolds, unambiguously, in the motion of a single paragraph, like a fist opening. It’s called “The Street Window” and was completed not long after Kafka’s graduation from law school. All a lone man has to do is go near a window that looks out upon a street.

And if he is in the mood of not desiring anything and only goes to his windowsill a tired man, with eyes turning from his public to heaven and back again, now wanting to look out and having thrown his head up a little, even then the horses below will draw him down into their train of wagons and tumult, and so last into the human harmony.

At some point, much as we talk a big game about needing to go it alone, we can’t help but be pulled to the window, to the noise and the voices. Come on into my hut and tell me about the demonology of garments, thong man. I’ll listen.

II.

Chopping Wood

My lung was fair at least out there, here where I’ve been for the last fortnight. I’ve not been able to see the doctor. But it can’t be so bad considering for instance that I was able—holy vanity!—to chop for an hour and more without getting tired, and yet was happy, for moments.

–Kafka, Letters to Milena (1917)

In the beginning his swing is wobbly, but gains a sort of clipped, if awkward, grace as he chops. It isn’t because he needs wood for any stove. This is pure sport. He’s a guest at a German spa. He’s forty. He’ll be dead of tuberculosis in seven years. But at the moment his lungs feel hardy. And he’s filled with expectations. He knows that as soon as he’s done he will go inside and write to Milena, his latest love, and tell her what he’s been up to by the woodpile. He’ll write, Well, I’ve been chopping some wood. Holy vanity. This from a man who would later (supposedly) beg that every trace of his life’s work be obliterated. Even he can’t help wanting an image of himself as a man chopping wood to lodge in Milena’s imagination. For a moment? For a night? For good? He chops and he chops.

In her obituary of Kafka, Milena will write that Kafka was condemned to see the world with “blinding clarity.” Consider the contradiction embedded in the phrase “blinding clarity.” By being prevented from seeing, he sees. But right now he’s just chopping wood. And as he chops, this man, Franz, is alive and in love (again), robust even. The ax squeaks like a mouse when he worries it from the log. He raises the ax again. The wood waits. He swings—then the sound—like a loud, distant, beautiful knock.

III.

Possible Father

In an essay on Kafka called “The I Without the Self,” W.H. Auden alludes briefly to a rumor “which, if true, might have occurred in a Kafka story.” The rumor, first circulated by Max Brod, is that Kafka once fathered a son but that the mother never told him the boy existed. The child, according to Brod, died in 1921 at the age of seven. Auden concludes: “The story cannot be verified because the mother was arrested by the Germans in 1944 and never heard from again.”

Let’s say for the moment that it’s true. Let’s say that the man who knew so uncomfortably much about fathers and sons was a father himself. He just doesn’t know it. At least not factually. Yet somewhere deep in his tortured psyche he has a nagging thought: I’m somebody’s father, too. One morning, at the end of the first decade of the last century, while on his way to his office at the insurance company, in a crowded tram, he spots a boy. An ordinary-looking little boy with a round head and bushy eyebrows, but there’s something familiar about him. It’s the eyes. There is something too wide about them. Kafka stares at the boy and the boy stares back. Or the boy seems to, anyway. He’s really only gazing, lazily, at a man in a suit, in a hat, on a packed morning tram. Other than the giveaway eyes, he’s just another fat-cheeked healthy boy with not an ounce of curiosity and, most remarkably, from the point of view of his putative father, no consecrated halo of isolation. Kafka looks at the boy’s feet. They aren’t small. They aren’t big. They are blessed average-sized feet—ordinary feet—and he thinks of them withdrawing from battered shoes at the end of a day like today and what it might be like to cradle them in his own softish hands.

IV.

Ceiling Dust

Decided to leave the next day. Gave notice. Stayed nevertheless.

–Kafka, Diary, July 28, 1914

This was in 2006. M and I had married a year earlier, after being together almost a decade. We returned to Prague because M had received a Fulbright to study Czech film. But more to the point, we’d once been happy there. We thought living there, again, might help make us happy again. Does this ever work? To return? As if it was the place itself and not who we used to be in the place.

That last night, I waited until M was asleep, wrote a note on a piece of paper towel, and dropped it on the kitchen table. Then I lugged a hastily stuffed duffel bag two miles to my friend Hugh’s apartment in Pankrác.

Hugh had been a colleague of mine at the law school back in 1999. He taught medieval legal history and was also the advisor of something called the Common Law Society, a club devoted to promoting the virtues of Anglo and American law, as well as the free market. Though I wasn’t teaching that second time in Prague (I was, as I loved to proclaim, at highbrow Fulbright gatherings, writing a novel), as a former visiting professor of Anglo and American law, I’d been invited to join, at Hugh’s suggestion, this extracurricular organization. I attended Common Law Society meetings once a week. I listened to presentations on civil procedure, contracts, and the inherent evilness of taxation. And at some point during that year, I stood with Hugh and the students for the annual photo. Studying this picture now, a photograph that amazingly can still be found on the Web, I can see that I was dazed. With my mop of unwashed hair, I look much younger than I actually was. I’m sure that I hadn’t taken a shower in days. Even so, I remember being grateful for the Common Law Society. It gave me someplace to go.

Because by then M’s struggle with paranoia had become completely debilitating. Though we’d been seeking help for years, usually from psychiatrists who were more than happy to prescribe medications but rarely took much time to speak with M, before we moved back to Prague neither of us had any clue about how bad things were going to turn. And at that time I wasn’t very sane myself. M and I were trapped in something I’ve never been able to talk about since. There are people who’ve known me for years who still know none of this. But it’s a story, ours (my version, anyway), and at some point stories need a little light of day.

We lived in Žižkov that year, under the television tower. Sculptures of babies crawl up and down the long pillars of the tower. I used to stand on our balcony and look at those babies defying gravity. But what comes back most vividly (I wish it didn’t) is how M shouted, how the smallest thing could set her off, and how embarrassed I used to get about what our Czech neighbors must think of us. Look at these Americans now, screaming their heads off. And M would become so upset with me for trying to make her be quiet—by shouting back at her, by trying to cup my hands over her mouth—that I often had to flee that apartment. I’d wander the city for hours, day and night, talking to myself, unsure of what to do. We had few friends then, and I couldn’t explain to those we did have what was going on because I didn’t understand it myself. This went on for months. Every morning seemed to bring a fresh catastrophe. The professors in the film department were out to get her. They were trying to sabotage her project. The landlord is screwing us out of the security deposit. But we haven’t moved out yet. How can she be screwing us over if we haven’t even moved out yet? Once, I had to knock her over in order to leave. Another time she wouldn’t stop hitting herself in the face. There are other things I refuse to remember. In between there were days of calm. For instance, one weekend we went by train to a place they call Bohemian Switzerland—another place we’d once been happy. M was reading something (she always read holding the book directly up to her nose), and she laughed out loud. I asked her to read it to me. I wish I remembered what it was, but I do remember that I didn’t think the line was that funny. I laughed, anyway, because I was so relieved to laugh, and I kept laughing and laughing until M said, Enough, already, it’s not that funny.

Also that winter our bathtub fell through the floor of the bathroom and into our neighbor’s apartment below. We came home and there was our tub in PhDr. Chroma’s living room. Nobody was hurt. We laughed then, too. Even Dr. Chroma laughed. For weeks, there was a massive hole in the bathroom. When we brushed our teeth we could look down and say hello to Dr. Chroma.

Most everything else was hell. For M’s increasingly frequent manic episodes, one Czech doctor recommended vitamins, and why not a kitten?

By that last night in Prague I was panicked and exhausted. The only thing I could think of to do was go home, wherever home was. I had no idea. San Francisco? Chicago? I’d never been to Hugh’s apartment. Somehow, after wandering around Pankrác in the dark, I finally found the right building and pressed the buzzer. When he opened the door, Hugh didn’t ask me any questions. He didn’t even look that surprised to see me. Hugh was from Scotland. He taught medieval legal history. We weren’t close friends, but sometimes he led me on long walks, tours of what he called great beheadings in Czech history. He’d point to a spot and say, Right here is where they sliced the neck of Ottar II. In this city, every corner staged a tragedy. Every square inch, Hugh would say, every building, every room—“Now, Peter, how about a coffee? Slavia or the cheap place in the library?”

That night Hugh immediately offered me his bed, the one I’d only just rousted him up from. He told me not to think twice about it, that come to think of it, he had reading to do. It was a one-room apartment. Hugh had built the sleeping loft to make room below for all his books. He said he’d built the loft too high, but that he’d become accustomed to it. He said he hoped the proximity to the ceiling wouldn’t bother me very much. He said, Take the bed, I’ve got reading to do, really. Take the bed.

I was in such bad shape that I did. I took the man’s bed.

The short night was so long. My nose touched the stucco ceiling as I tried to sleep. The ceiling was dusty. I kept wondering why the dust hadn’t fallen to the floor, why it clung there to the stucco. Maybe this was why they call it stucco? I thought about this while I waited for sleep that never came. Outside Hugh’s window was a highway. Tourists don’t visit Pankrác. It’s only famous for the prison. Václav Havel was once an inmate. In the dark I listened to the cars as they accelerated and vanished. At one point I noticed the bar of light under the bathroom door. Hugh hadn’t wanted to disturb me. He’d retreated to the bathroom to read. In the lulls in the highway noise, I could hear him turning pages. In a few hours, M will wake up and read the paper towel.

Kafka once wrote that writing was a form of prayer. I have no recollection of what I wrote on that paper towel, but I’d like to think it was, in some way, a prayer for us both. She’ll be on her own now. And I’ll leave this city for good in the morning, but this night will go on and on, still does go on and on, my nose in the dust of the ceiling.

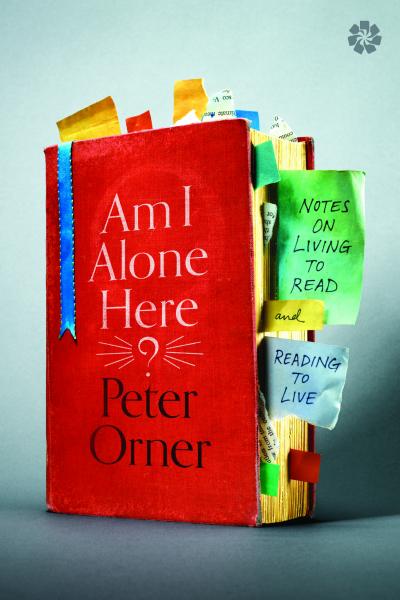

From AM I ALONE HERE? NOTES ON LIVING TO READ AND READING TO LIVE. Used with permission of Catapult. Copyright 2016 by Peter Orner.