Stop Obsessing: A Reading List for Finding Joy in Irrelevance

Amy Leach on the Freedom of Lightening Up

They’re always talking about being up a creek without a paddle, as if a paddle were the only thing you could be up a creek without. Of course, when you’re up a creek the paddle is the relevant thing, but you can also be up a creek without a parakeet or a pagoda or a Greek-Syriac lexicon. I’ve been up a creek without a tuxedo before, and once I even found myself up a creek with no tuba.

Similarly, when they call someone ill-informed, it seems like they’re always referring to relevant issues. But someone can be ill-informed about irrelevant issues, too. Not only do I not know much about the Supreme Court—I also don’t know much about the Grindletonians, the glyptodonts, the Quasi-War, the Dunker denomination, or “Irish Marvels Which Have Miraculous Origins.” Nor do I know much about Irish marvels with ordinary origins. Not only can I not bake sandwich bread, I also cannot bake knishes or kringles or bizcochitos. Not only do I not have millions of dollars—I also don’t have millions of kopecks or drachmas or shekels or millions of those big stone disks they use on the island of Yap.

Everybody wants to be relevant these days, and everybody wants everybody else to be relevant, too. It can seem that relevance is the only virtue, or that among virtues relevance holds a despotic ascendancy. But of course relevance is relative. What is relevant to an English schoolgirl—impressive vocabulary, schoolroom society, simple rules to avoid getting poisoned, being smarter than Mabel—may not be relevant to a walrus or a crab or an insane duchess.

If you find yourself oppressively preoccupied with relevant issues, just start a conversation with an eaglet and a duck; go croqueting with a flamingo as your mallet; attend a tea party with a doormouse and a hare and a hatter. This will make a hash of your relevance, for it will not even register with your interlocutors.

Our thoughts could be starbound; why do we think like personnel?

I realize I am making it sound too easy; I know flamingos can be suspicious and eaglets are not always in the mood for conversation. I also know that walruses often have prior engagements—how many times have I sent out the invitations, set up the card table out by the poppies in the backyard, prepared the tea and buttered the toast, but then only people show up, all of them sane? Being snubbed by walruses—this is why I read, because some writers are almost as good as walruses for joggling the head, freeing it of relevant concerns. Below is a list of the writers I turn to whenever I cannot find a walrus.

Hafiz. Presumably there were current issues in 14th-century Persia. A writer could have been relevant even then. However, Hafiz wrote poems about swapping jokes with the sun, the universe being a tambourine, rabbits playing cymbals, planets gone crazy. Because of his absurd topics, Hafiz is now as irrelevant as ever: Hafiz is timelessly irrelevant. Here is part of a poem that appears to describe his own writing process:

The mule I sit on while I recite

Starts off in one direction

But then gets drunk

And lost in

Heaven.

The anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing. First of all, is there anything more irrelevant than anonymity? Furthermore, this mystical 14th-century Englishperson directs you, the reader, to pursue the absence of knowledge, to pitch all of your information into the Cloud of Forgetting and to pitch yourself into the Cloud of Unknowing and make your home there. If we all took Anonymous’ advice and relocated to the clouds, I wonder what would become of the phone factories and the fact factories.

Ovid. A charming girl turns into a charming cow. Her miserably immortal father laments: “For me death cannot end my woes. Sad bane to be a god!” All the daughter can do is moo. Someone turns into a mint plant, someone turns into a screech owl, someone turns into a constellation. I wonder how attached they had been to their previous identities.

Imagine the person who for twenty years has been establishing her professional identity as a person, publishing pro-person articles in academic journals, participating in person panels, etc., but now, right after having scored an interview for a plum university job as Professor of Personness, she is turned into a cucumber plant. Say she decides to go ahead and interview anyway: she takes the hotel elevator up to the fifth floor, taps her green fruits tentatively on the door to the room where the hiring committee has convened, shuffles in, takes her coat off, and the committee says, “Oh, okay… Well, um… we… wow… from your CV we had you pegged as a person.”

God. That old author of the Fourth Commandment would give the animal workers (and servants and foreigners) every seventh day off. If followed, this whimsical commandment would slow down the dollarization of the world.

John Milton. Because pamphlets are so flimsily made, they tend to be written about urgent, pressing, timely topics, like peer pressure and pickles and salvation. But of all the pamphlets I have read, pamphlets regarding New and Old Pickle Recipes and How to Plan Your Children and How to Repair Zippers and How to Go to Heaven (a clear behavioral plan that does not include the reciting of poems while sitting on a sozzled mule), my favorite is an old obsolete one called Areopagitica, in which Mr. Milton tells the church to butt out. This was back when, before a book was published, it had to first be approved by a bunch of interfering friars.

To fill up the measure of encroachment, their last invention was to ordain that no Book, pamphlet, or paper should be Printed (as if St. Peter had bequeath’d them the keys of the Presse also out of Paradise) unlesse it were approv’d and licenc’t under the hands of two or three glutton Friers. For example:

Let the Chancellor Cini be pleas’d to see if in this present work be contain’d ought that may withstand the Printing. –Vincent Rabbatta, Vicar of Florence

I have seen this present work, and finde nothing athwart the Catholick faith and good manners: in witness whereof I have given, &c. –Nicolo Cini, Chancellor of Florence.

Attending the precedent relation, it is allow’d that this present work of Davanzati may be printed. –Vincent Rabbatta, &c.

It may be printed, July 15. –Friar Simon Mompei d’Amelia, Chancellor of the holy office in Florence.

Of course there are no glutton friars signing off on our books anymore. The most gluttonous among us—the grizzly bears—are so busy being gluttonous they don’t have time to scrutinize potentially subversive material. This is why there are no craven books beholden to bears.

In some modern societies there are no censors whatsoever, except for the most censorious censors of all—the censors in the mind, those officers policing our thoughts to ensure there is “nothing athwart.” Nothing athwart convention, nothing athwart consensus—nothing athwart relevance. Our thoughts could be starbound; why do we think like personnel? At what point do persons become personnel? They sure as pandemonium don’t start out that way. In any case, as fat as those old friars were, they weren’t as fat as God, who does not censor us at all.

__________________________________

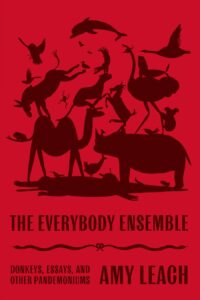

Excerpted from The Everybody Ensemble: Donkeys, Essays, and Other Pandemoniums by Amy Leach. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Amy Leach. All rights reserved.

Amy Leach

Amy Leach grew up in Texas and earned her MFA from the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Her work has appeared in The Best American Essays, The Best American Science and Nature Writing, and numerous other publications, including Granta, A Public Space, Orion, Tin House, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is a recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award, a Rona Jaffe Foundation Award, and a Pushcart Prize. Her first book was Things That Are. Leach lives in Montana.