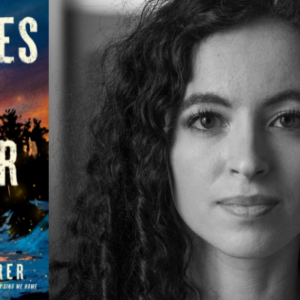

Stop Looking for One War Story to Make Sense of All Wars

Matt Young on the Romanticized Image of the Warrior Poet

Sometimes in conversations about my book, the person with whom I’m speaking to brings up how unusual it is for Marines—especially enlisted infantry Marines—to write so articulately, poetically, and lyrically. It’s meant as a compliment, so I nod and smile, make a self-deprecating joke about being a dumb knuckle dragger. The person usually follows up by asking if I read and wrote a lot during my enlistment or if it was hard being an artistic type in the military. The main supposition being that the average grunt must be too stupid to write. But underlying it all is the idea that veteran writers have certain personality traits—that they have to be wily, intelligent outsiders who don’t take kindly to routine.

At my high school in Indiana I was a C-average student. I never read T.E. Lawrence in country. I never quoted Stephen Crane before patrols or recited Alfred, Lord Tennyson before raids. All of this is to say: I was not that unique, standout, thoughtful anomaly people have in their heads of veteran writers. I didn’t keep a journal or write or even read very much aside from Marine Corps publications and James Patterson novels while I was enlisted. I watched a lot of porn. I wasn’t quirky, individualistic, or flighty. I didn’t think about the legality and justification of the war until I left the Marines. The military—and especially the Marine Corps—doesn’t want quirky. It wants people who have the ability to think and problem solve and make decisions. But they also want people who do those things while following the orders of their superiors mechanically.

The romantic image of the warrior poet is pervasive throughout our culture. It’s a symptom of the civilian-military divide. Who decides to share their stories, who does not, and what kinds of stories are culturally acceptable are root causes of that symptom. Most memoirs written and published about the Forever Wars are from the perspective of officers or elite forces. The average enlisted grunt experience gets a lack of airplay.

“I tried to brandish my perspective like a hot iron and in doing so I discounted the experiences of others, both military and civilian, as well as cheapened and made facile my own.”

Many of the problems concerning enlisted representation have to do with the culture of silence surrounding grunt units. We’re told not to talk about what we do. We’re told we’re malingers if we go to sick call. We’re told to lie on psyche evaluations lest we be booted from our units and locked in padded cells. We’re told people won’t understand us and they’ll twist our words and make us into monsters.

I have felt like a monster. I am ashamed of a lot of the things I did—detaining young Iraqi boys, bearing witness to the torture of detainees, cheating on my then-fiancée. When I was finally ready to talk about that stuff I felt I had to have some deep philosophical thing to say, because that’s what I’d seen other vets doing. I wanted to present my story like I’d learned something important from my experience or had gained some knowledge others couldn’t. I tried to brandish my perspective like a hot iron and in doing so I discounted the experiences of others, both military and civilian, as well as cheapened and made facile my own. It wasn’t my voice and smart readers could see through my bullshit. I couldn’t imagine an alternative—I felt locked into the styles and narratives I’d been reading. I felt like people didn’t want to hear my voice.

To tell our stories well we’ve got to ignore how other people think our voices should be heard. We’ve got to ignore what other people think are valid experiences to write about. We’ve got to think about what mattered to us when we were at war. We’ve got to think about what we wish we’d known. We’ve got to think about the things that made us laugh and want to die. We’ve got to realize there might not be a lesson in our experience, there might be no moral, there might not be a tight bow with which to wrap up our stories. We’ve got to give ourselves time and distance to process and understand and then we’ve got to shine a holy light of brutal honesty in the places civilians aren’t allowed to see. Show them what war is to the individual—create a primary source mosaic of experience.

Part of my mosaic: War is a place where sergeants taught me how to make portable masturbatory devices, where they ran me until I puked up the beer they’d fed me the night before, where they pounded rank insignia into my collarbones and blood-striped my legs when I picked up the rank of corporal, where I hallucinated from lack of sleep, and jerked off to stay awake. War is cold and boring and full of stars and love and dust like powder foundation and biceps and yelling kids and soccer balls and power lines and the smell of bread cooking in clay ovens and frosted dirt and kerosene and pirated movies and gunshots and laughter and hate and fear and being yelled at and struck by widows and drinking tea on a rooftop in full gear at four in the morning when the sun rises angry and burning.

People keep looking for a definitive experience that will help make sense of the wars. It doesn’t exist. There’s no Forever War Rosetta Stone. Sharing our stories and perspectives and truths is a way to do that. The Marines indoctrinated me to believe I was a cog in the machine, indistinguishable from any other. But every enlisted grunt’s service experience is unique. My experience as a common enlisted grunt was my own—as much as I felt like it wasn’t at the time or as much as the media I surrounded myself with and my higher ups told me it wasn’t. It took a long time to figure that out. I wish I’d had someone to tell me different.

Matt Young

Matt Young is the author of the memoir, Eat the Apple (Bloomsbury, 2018), and the novel, End of Active Service (Bloomsbury, 2024). His stories and essays have appeared in TIME, Granta, Tin House, Catapult, and The Cincinnati Review among other publications. He is the recipient of fellowships from Words After War and The Carey Institute for Global Good, and teaches composition, literature, and creative writing at Centralia College in Washington.