Startlement and Stillness: David Searcy on Photography

In Praise of Clarity and Accidental Allegory

Photographs seem to suggest the possibility of stillness. Of our stillness—as completion. As arrival. That’s because what’s most conspicuously presented isn’t really the subject itself (a painting, after all, does that) so much as the act, the singular fact, of observation. The beholding. The suggestion thus extending to the lens and the photographer whose place you take when looking at a photograph. You think (by now unconsciously, of course, but fundamentally) you’re fastened in that place, that observation. You’re complicit in that stillness, can’t help feeling it’s available—and you, your migratory self, resolvable within it. We’re all primitives with this. We can’t believe it, but it’s true because it’s random, uncontrived. A photograph—to the extent it’s not so tarted up it doesn’t look like one—is accidental. Startling. Stumbled upon. Our startlement is buried but it’s there. We do not like it but we keep it—in our wallets or our iPhones. Close to us—the proof of us, our families, pets. We want the proof and bear the startlement. Each time, each ordinary time we take our photos out and show them around, each time I swear we pause upon our desert wandering, our herd of zebu anxious and confused, to think a moment where we are and where proceeding as the lifted dust drifts on ahead like ghosts.

The photograph has no opinion. Notwithstanding the photographer’s intention, and, again, to the extent that it’s not touched up, hand-colored, messed with as they used to like to do so much with portraits, to suppress, perhaps, that startled sense of randomness, the camera’s deep indifference that devalues all to data—there’s a chance, after all, that it might be true, as everything else in a photograph seems true. That’s how you know that it’s a photograph. No inference is required. Whatever we think about the content is external, unimportant to the photograph, the central fact whose simple overwhelming revelation is the thinness of that moment, of our presence in that still and uniform and endless moment, before judgment is imposed.

We take core samples with our cameras, random samples—they keep coming back the same. Of course we want to tart them up. Drop phony backgrounds in, apply a little color, deckled edges for that handmade-paper look—and for the artiest chemical photographs these days, you let the edges of the frame creep into the print, enlist, as ornament, the randomness itself to show you mean it, to provide essential value after the fact. Dress up the dead. We can’t abide that they are random, we are random, arbitrary, accidental—to the extent more real, more random. To the extent more nearly graspable, possessable: more indistinct, diffuse. That’s the bewilderment. The emptiness. The trick. With every photograph you pause with it and reach for it—not consciously, of course, but still you do. And yet there is no point of purchase. Any painted picture’s surface is articulate with variable and graspable intention and conviction interacting to extend a thought as simple as Oh, look. Whereas the surface of a photograph, beneath what we impute, is unrelieved— conviction uniform, disinterested as glass. Your grasp just slips away. It looks so real, as if such things were real. So you can’t help yourself, yet every time you come up empty-handed.

A photograph—to the extent it’s not so tarted up it doesn’t look like one—is accidental. Startling. Stumbled upon. Our startlement is buried but it’s there.

Take, for example, one of those strangely typical nineteenth-century funerary photographs—of the taxidermic style where the departed is dressed up, propped up to join the family group, to return, as it were, from behind the curtain to take a bow. It plays, so clearly and so sadly, to the basic revelation of photography—as if these people know they are reduced to equal value. In order to have their loved one back, they must assemble in a place where living and dead have equal value. Which the photograph— the essential fact of the photograph—provides. The blank-faced child is revived, or else the family group is seen to join her in mortality. In either case the family is reconstituted. Not imagined, wished as in a painting or the mediated contact of the death mask, but demonstrably, indifferently, and truly as whatever enters the photograph is instantly beheld with the same astonished yet disinterested conviction—everything reduced to the fact of itself, one fact as good as another. Point the camera in any direction—it’s the same. The tripod kicked, the camera skewed from the family group to take in floral-papered wall, screen door, the bleary, tilted, overexposed beyond—some stubbly cotton field or something—way on out to where the emulsion breaks apart and lets you escape the grief and the cotton field into the understanding that the photographic moment, thin as paper, keeps on going, the essential insubstantial fact with you, your eyes wide open, right on out into the emptiness.

The photographic process is so passive, so inevitable you’d think there must be similar, simple, natural intuitions, revelations all around us all the time. You think of shadows, mirrors, fossils. But these things, one way or another, do not separate from everyday experience—they’re not still or they’re not passive or not flat. They move with us. We move around them. Or they join the world’s activity as projections. They don’t fix and represent our observation. Even mirrors do not hold our looking up to us like that. If there were something like a photograph then it would be a photograph. A thing resembling knowing would be knowing.

There seems practically nothing to it. Imagine a cave somewhere, like Plato’s in a way, but with a single tiny opening to the outside, through which light, as in a pinhole camera, beams and casts an image onto the opposite wall composed of a mineral substance (I have no idea if such exists in nature) that will fade upon exposure to the light. I’m sure it would require a very long exposure, which would wash out the ephemera—passing nomads, flights of birds—to leave at last, as after a hundred or a hundred thousand years the hole is closed by natural processes, a sort of airbrushed picture in the dark, a photograph of empty landscape. Ground and sky.

Why shouldn’t motion pictures amplify the startlement of photographs? Accumulate it? Overwhelm us with it? Well, at even the most particular, functional level, it refuses to accumulate. Each certainty surrenders to the next, conviction lost to continuity and, finally, to intention, somewhat like that of those rock displays you see sometimes in curio shops where individually striking, primitive chunks of quartz and agate, pyrite, petrified wood, and so forth have been glued onto a board to form a pattern—star or flower or the state of Texas, say—which absolutely kills the bright surprise of each, drawn into service of the ornamental narrative. Motion pictures reassimilate the photograph to ordinary life. The movement seems to be enough to pace experience, let the photographic glance fade into ours the way a lens placed in a liquid of the same refractive index disappears.

So articulate a photographic moment seems to offer a kind of purchase toward belief. Again and again. Toward resolution out of emptiness.

Here is a photograph I found among my mother’s family pictures years ago, and which I find myself returning to from time to time as it seems to strain so sadly to assimilate, reassimilate, to the world. A little girl in a swing is swinging toward the camera. Just past focus. Blank and round-faced little girl in a plain, pale frock somewhere in Omaha, Nebraska, it is thought. About 1910. I’d guess she’s three or four—that anti-telescopic age when the vacuum we are born with still inhabits us with such an active longing. She completely fills the center, squinting straight back at the camera with that blankness children tend to direct toward cameras as if they’ve been asked a question they can’t answer. She’s suspended between two fundamental states: at left, these grim dark brick or painted clapboard apartments— very bleak and institutional-looking, from which, one imagines, she’s emerged; at right, bleached out in the general overexposure, fading into the blankness of the sky, a field of grass that looks as if it might run out to the edge of the world. She’s unendurably suspended. Like the funerary photograph, the content here responds to, sort of brackets, the primitive photographic fact—that unresolvable stillness. Dark, opaque arrival on the one hand; on the other all that clear and grassy migratory emptiness. She’s specified yet lost. As lost. She wants to emerge from this, to meet us halfway—look how she swings out toward us, going a little fuzzy, though, as we reach out to take her. We can’t help it, even as she starts to blur.

What if we nudge her into cinematic motion? Can we bring her into the world that way, yet keep that stark, indifferent specificity? That certainty? Maintain our concentration, our complicity in that moment—our belief in her, essentially? Crank it slowly—just a couple of frames, click, click, completes her movement toward us, blurs her slightly more; we’re going to lose her. We are losing concentration. Just that much and we can tell. Now speed it up. She swings away toward focus— Oh my God, a breeze. Across the grass, a little breeze to ruffle her high-cut bangs, her cotton dress—a little too large, inherited probably. Bring it up to standard eighteen frames per second and that’s it. The striking, primitive, certain fact of her is washed into the narrative with us. We cannot join her—not, at least, in that still certainty—after all. She blurs away—so we receive her as an analogue of events which, after all, will have to do. She goes from specified-yet-lost to found-yet-generalized. A quantum physics–sounding sort of problem. Our belief in her diffused into belief in a child like that in a moment like that as she swings back and forth like a science demonstration to exhaust some stored potential. It’s exhausting.

So articulate a photographic moment seems to offer a kind of purchase toward belief. Again and again. Toward resolution out of emptiness. Just look at it—the clarity, the accidental allegory. We can’t help but think it should be possible to come to terms with the fact of her on a day like that, in a clean white dress like that in 1910. We can’t just leave her. We’re compelled to join the fact of that old photograph, to take her from the swing, so gently, carefully— she’s us of course, the unlocatable self, let’s say the soul; that’s part of the allegory—lift her up and fold her white dress under, hold her head against our shoulder as we would, as anyone would, with some lost child in such bleak circumstances. Rock her side to side and feel the breeze and smell the grass and try to comfort her for having to be here so randomly, indifferently. For having the same value as empty landscape.

_____________________________________________

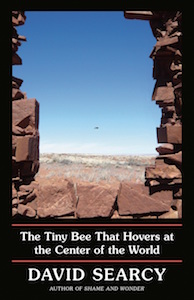

From the book THE TINY BEE THAT HOVERS AT THE CENTER OF THE WORLD by David Searcy. Copyright © 2021 by David Searcy. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

David Searcy

David Searcy is the author of the novels Ordinary Horror and Last Things (Viking, 2001 and 2002). His first book of non-fiction, Shame and Wonder, was published by Random House in January 2016 and was selected for the Spring B&N Discover Great New Writers Program. Chapters from Shame and Wonder were excerpted in The Paris Review and subsequently in Best American Essays 2013 (editor, Cheryl Strayed) and Granta (2013). David Searcy was included, at the age of 71, in the “Future of New Writing” issue of Freeman’s magazine. He is at work on another essay collection, from which several chapters have been published in magazines & newspapers ranging from The New York Times Magazine to the Oxford American.