Meghan Daum, Live in the Capital

Three Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids

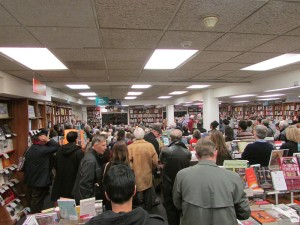

Some author events draw a crowd because the audience is a devotee of the author, or because the topic is controversial. Sometimes, though, the crowd is drawn to the book event for the best of both reasons. Spending your Saturday night at a bookstore in DC to discuss feminism, parenting, and authorial intent over your own life is my idea of a good time. Not surprisingly to anyone reading this, I’m not alone.

Politics & Prose bookstore on Connecticut Avenue in North West quadrant of DC is known for being a sort of year-round stationary literary festival combined with a model UN. The audience at events are intent, engaged, and definitely opinionated. Saturday night was a prime example with hipsters, literati, and longtime survivors of the beltway life gathered en masse to discuss Selfish, Shallow and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision NOT to Have Kids. Selfish is a collection of essays selected and edited by Meghan Daum, Gen X essayist and literary girl crush. For weeks the staff at Politics & Prose bookstore and I were buzzing about meeting the author whose work reminded us to find authenticity in our work and daily lives. This collection was conceived by Daum in order to start the conversation between parents and non-parents afresh. She started with her own “camp”: the intentionally childless.

Our night opened with novelist, mother, and Politics & Prose employee Susan Coll introducing the powerhouse panel ready to discuss the book of essays immediately declared “provocative” by the majority of reviewers. The conversation-driven panel was made up of poet and DC resident Sandra Beasley, novelist and contributor to the collection Elliott Holt, and Daum. Coll’s introduction set the tone for the evening: emphasizing on the tension between the personal choice to not have children and the public provocation this often causes. Coll’s excitement matched the audiences. I was trepidatious, curious, and game. How could we have a conversation about childlessness and a full life without devolving into the usual bickering or blame? What did authors have to offer here that was unique?

There was to be no sugar-coating for this panel. Daum explained to Beasley that this book was about rebooting the conversation. “The word ‘selfish’ gets volleyed back and forth a lot… who’s more selfish, more hedonistic and ruining the world at a faster pace? And I find that so reductive. Because it’s such an important conversation and I think it’s important to have it in a thoughtful, respectful way. I wanted to get away from these punch lines.” A promising start, writers prepared to go beyond the politics, the statistics, and get to some hard questions: Why is this so uncomfortable? What are our assumptions? How can we get over the flip reply to this invasive question? How can we get over asking it at all? When does the personal become the public?

Beasley asked Holt what it was like to be asked these questions (Daum had recalled the awkward email requests to authors she was hoping were intentionally childless). Holt continued, “It’s nice when you have 4,000 words to explain it [beyond] cliches like, ‘Eh, that ship has sailed.’ That’s my favorite… That ship full of ovaries, the eggs just went out to sea… But I have many close friends who are my age who have young children. No one has ever said to them, ‘Why did you have children?’ Nobody ever asks people with children why they have children; they only ask those of us who don’t why we don’t have children. And it’s very weird because that’s a very personal question and I get asked it all the time by people who don’t know me very well.”

Much of the audience was women. This reflected the make-up of the book, too, which contains 13 essays by female authors and three by male authors. Daum and Holt touched on this aspect of the book repeatedly, Holt calling the make up inevitable because we still live in a gendered society in which women cannot simply be a “childless” or an “unmarried.” There has to be a story. There must be advice to help a woman want to be a mother. There is still a need to explain ourselves.

The three authors discussed the pressure women have to avoid being perceived as child haters when you’re a woman who doesn’t want children, or the idea that you are not a full feminist wanting to want to be a woman with children. Helen Gurley Brown’s “having it all” is a myth, though Daum took particular delight in pointing out that when Brown, founder of Cosmopolitan, said “having it all” she meant more boy toys, cash, and clear alcohol, not a high-profile career, 2.5 kids, and lack of sleep.

Daum, Holt, and Beasley were ready to steer us away from myths, and into a fuller, more complex reality. Beasley quoted her mother’s wisdom upon learning that her daughter did not wish to have a child, “There are many roads to happiness.”

Beasley hit on the core of the book by reminding us, “This is a collection of essays by writers… I have used the line, ‘I decided not to have babies, I’m gonna have books instead’ and it’s a really snotty line, but it was in the moment the best I could come up with as this kind of self-defensive protection and maybe that’s something writers bring to the table.” Holt jumped in, “Well I think it’s probably, to some extent, some human impulse to wanna leave something behind, even though we’re kidding ourselves because, you know, we’re all gonna die.” I laughed a little too loudly here, but luckily was not alone. Holt continued, “I mean, whatever, we’re gone. Mortality is terrifying and you want to leave something behind. I think for writers, since we do leave published works behind, maybe the legacy pressure is less—we’re leaving something else behind… But I will admit that part of coming to terms in my piece with the fact I wasn’t going to have children was because I finished my novel.”

Daum continued, “Ultimately people are going to do what they want to do… But the fact of the matter is that most writers have kids! I don’t think it’s any sort of one thing. I think it’s really hard for people to say: I actually just don’t want to do this and that’s the reason. And that’s what I’m hoping, you know, as the years go on and this conversation continues to evolve that that can be an acceptable answer in and of itself.”

This was the moment of collective nodding. Beasley asked, “What was missing from this collection? If there was a 17th essay, what would it be?” Daum’s response hit on the only weak point in the book to me: not enough (though not completely absent) LQBTQ representation. “I would have loved to have found, male or female, someone who is gay, and, you know it’s like Fran Lebowitz always says, the greatest thing about being gay used to be that you didn’t have to go into the military, and you didn’t have to get married, and you didn’t have to have children, and that has now been completely obliterated. And I’d be curious to have somebody talk about the countercultural trappings as it used to be defined and how that has been blown away by the heteronormative, bourgeois expectations on everybody.” I wondered too, for the next volume of the book, about gay authors not only unimpressed with futurity, but transgendered authors who choose not to engage with parenting.

An audience member made the excellent connection between this book and the recent publication Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own by journalist Kate Bolick. Elliott Holt had recently reviewed the book. “The fact that we’re forced to have this conversation is still depressing to me. When people talk about either of these books as provocative I’m like, ‘Really? Is this really a provocative thing to say?’ It just mystifies people. It is hard to separate what you want from what you’re supposed to want.”

“I want us to think of each other as partners,” Daum said towards the end of the evening. A child’s crying served as background noise to the close of the event, lending credence to Daum’s point: we’re in this together, whether you want to have kids or not. Let’s have a conversation, or at least read some books.

Hannah Depp

Hannah is the merchandising manager at Politics & Prose Bookstore in Washington, DC. She is a lover of dead white guy lit, a recovering theatre kid, and holds degrees in several unemployable, massively satisfying Humanities. She will find a bookstore or a tea shop within the first hour of every trip.