Sonia Manzano on Finding Her Way to Sesame Street

”It exalted me, and others like me, to be on the show.”

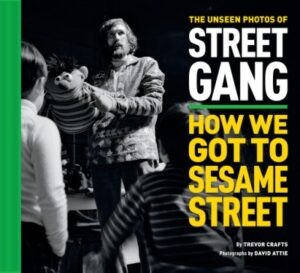

Above: Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment

Sesame Street was shot out a of a cannon in 1969, fueled by the social unrest of Black Americans tired of being treated as second-class citizens, young people marching on Washington to protest an unpopular war, farmworkers demanding decent labor conditions—the list of grievances that were being protested went on and on. It seemed everyone in the late 60s in America was in for a change.

By night I observed the goings-on from my home in the Bronx, and by day with my friends at the High School of Performing Arts. And just when I was beginning to think that Puerto Ricans like myself were doomed to watch from the sidelines, a group called the Young Lords protested the lack of garbage pickup in El Barrio by setting the trash on fire, finally getting the attention of New York City officials. That protest fired up my heart and mind as well, making me feel like a part of society. Perhaps even on some level also enabling me to feel enough a part of things to find my way to Sesame Street. Why not? Sesame Street grabbed me by the throat even before I was cast as Maria.

Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment

Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment

I first saw Sesame Street at the student union of Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh—and I was stunned. Were those really Black people on television? Were they actually talking to me from someplace in the city I was born? Everyone at the student union who watched the show with me that day was bemused and intrigued by what they saw. It was so funny, provocative, different, and smart.

But my white classmates couldn’t have understood my own excitement at seeing Lorretta Long playing Susan and Matt Robinson playing Gordon. The thrill of seeing people of color on television was mine alone, except of course, for other people of color who happened to be watching somewhere else in America. All at once, I remembered that in all the television I had ever watched as a child, I never saw anyone who looked like me or lived in a neighborhood similar to mine. In fact, I remembered aligning myself with any dark-haired character on television, including the Mexican actor who guest starred as a gardener on the popular 50s television show Father Knows Best. Trying to fit into a pre-made mold had been exhausting, and worse, it made me question where I stood in a society that refused to see me.

But here was Sesame Street. It was as if the producers took everything that was going on in American society, funneled it through a straw, and blasted it on television. And if the things on the screen excited me—imagine what diving into the thick of things felt like when I got cast as Maria? Behind the scenes I saw colliding forces of creative people. Everyday creative fervor spread like a fever. Passions ran amok. There was a feeling of being on the move, of riding high, of enjoying and seeking exhausting exuberance. What was I to do in this mix?

Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment

Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment

Matt Robinson gave me a clue as to how I would contribute when he pulled me aside saying, “You’re not here to be the cute little Puerto Rican.You have to make sure the Puerto Rican content is on point!” At first, I was surprised and self-conscious. Me? I thought. Who elected me mayor of Puerto Ricans? But I used his point as a stepping-stone to get on board.

My part became clearer the day creator/producer Jon Stone furiously pulled me into the makeup room and scolded the makeup artist saying, “I go through all the trouble of hiring a real person, and you make her up to look like a Kewpie doll.” He was angry, the makeup artist was chagrined, and I soberly began to look at the reflection of my face coming clear in the mirror as she removed my make-up. I was not to play a part or be anyone’s preconceived notion of a Puerto Rican. I was to be myself.

But I had one last hurdle to overcome. Puppeteers Frank Oz, Carroll Spinney, Jerry Nelson, and of course Jim Henson managed to radiate characters from their finger- tips and through the furry fabric of the Muppets’ faces.

Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment.

Photo by David Attie/Courtesy Macrocosm Entertainment.

How could I put aside my own amazement of their talent long enough to perform with them? How was I going to act alongside handfuls of fur?

Once, while playing a scene with Grover, I continued to look at Frank Oz, the puppeteer down at my feet, instead of the Grover puppet Frank was holding close to my face. “Quit looking at that man down there,” he quipped as Grover, bringing my attention up to the character emanating from his fingertips. Everyone laughed. The way to work with Muppets became obvious: I was to set up the joke and let the Muppet come in with the punch line. I became—what used to be called in old comic parlance—the straight man! I was on my way.

As the years went by, I began to see how Sesame Street gave us as opportunity to take a good look at ourselves. Television can help us celebrate our human universality. The medium wore me down when I wasn’t represented on it, so it exalted me, and others like me, to be on the show.

__________________________________________________

Excerpted from THE UNSEEN PHOTOS OF STREET GANG: HOW WE GOT TO SESAME STREET by Trevor Crafts. Published by Abrams Books. Copyright © 2021 by Trevor Crafts. All rights reserved.