So You’ve Decided to Write: Will You Tell the Truth?

Terry McDonell on the Deal All Writers Have to Make With Themselves

Editors should never preach and that is not my intention, but whether you’re a journalist or a writer of fiction or an editor of either one, when you look in the mirror you should think tireless or dogged or maybe even a stronger word (indefatigable?) to describe what you need to be to become successful, and what you should be as you go after the truth—which is your job. I am not talking about the White House press corps and all the others busting alternative facts on the front lines of the fake news war. They are elite in their own way, which is why they cover each other with such pride. Good for them.

I am talking about something different, looking for the smoking gun but also for the occasional blip that at first may seem odd but then suddenly makes complete sense—like finding out that the Dalai Lama likes to fix wristwatches. This is a small truth, a fact, loaded with implications because of the synchronous orbits it shares with His Holiness’s day job. Squint at it.

Look closely, too, at the reach between, say, the Ogaden shepherd with his cell phone in Ethiopia and the Seattle software engineer sipping his Ogaden Americano. This is different from the false range that appears so often in awed journalism about entertainment (“from Brad Pitt to George Clooney”) or the sameness of the details across the cable talk news cycles (“Jared Kushner said what?”). The Ogaden reach can be a zip line for all the complicated and contradictory ornaments you want to hang on it as a fiction writer or long-form journalist.

Fiction has its own truth in what is made up to help us see what is real. (One morning, when Gregor Samsa awoke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin.) But Gregor is not going to sue, and journalists have to watch out for that—even when their most important job is telling true stories. Here is the definition of “journalistic truth” that comes out of the Journalism and Media division of the Pew Research Center: “A process that begins with the professional discipline of assembling and verifying facts. Then journalists try to convey a fair and reliable account of their meaning, valid for now, subject to further investigation.”

This is good thinking but it often gets bumpy in practice. Objectivity is an illusion. Every writer knows that, and makes his or her own deal. If you’re a journalist, this is very big. The unwiped truth is that the so-called journalism of empathy—written with an understanding of the point of view of sources and building a reciprocal relationship with readers—is a convenient escalator to ethical justification. That’s why it’s so hard. At its best (recently Hue 1968, by Mark Bowden; Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann; and No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes by Anand Gopal), you get the most powerful non-fiction narratives. At worst, truth never gets in the way.

In her book I Remember Nothing, Nora Ephron wrote in a chapter called “Journalism: A Love Story” that there is no such thing as the truth, that people are constantly misquoted, that the media is full of conspiracies “and that, in any case, ineptness is a kind of conspiracy.” She was no longer a journalist when she wrote that but early in her career Ephron reported for Newsweek, the New York Post, wrote a column for Esquire, and later did a rewrite of the script for All the President’s Men. Her summarizing thought in the chapter is that “emotional detachment and cynicism get you only so far. But for many years I was in love with journalism.”

Loving journalism is usually the beginning of the story. Then, inevitably, you find that some of the best journalists are troubled by what they do. Hilariously combative old Gore Vidal called source betrayal “the iron law of journalism.”

With her usual reverberating truth, Joan Didion wrote in her 1968 preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem, “Writers are always selling somebody out.” This line has been used so many times that the point of her ethical dilemma becomes the death of a thousand cuts. But you do understand, and figure it is never any writer’s intention to sell anyone out, until you come across the even more disturbing quote, from Janet Malcolm. It is the thesis of her 1990 book The Journalist and the Murderer. It’s also her lede:

Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.

The indictment is more powerful because Malcolm never renders herself immune. She is, in this way, indefatigable. But so too is the truth, even when there are many truths and they are built on alternative facts. All writers need to think about that.

Head here to read more writing advice from Terry McDonell.

__________________________________

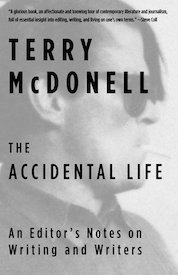

Adapted from The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers, by Terry McDonell (who is a cofounder of this website), published this month by Vintage. TerryMcDonell.com.