So You've Decided to Write: On Editing James Salter

Terry McDonell on Working with a "Writer's Writer"

You had to find things out about Jim Salter. He never volunteered, never talked about himself, never. If you asked, he would answer questions, and sometimes tell a story if you pushed. But that’s not what I mean.

His great confidence had a rightness about it that left him seemingly without vanity. I believe his work gave him that, and so too did the way he lived with his talent. In his “Art of Fiction” interview, he told the Paris Review that there was a right way to live and that some values were untarnishable.

The immense depth of that was in his descriptions of the intimacies of love and the details of disappointment and loss and regret, and it made reading him an ecstatic experience. You read to see what would happen, sure, but you read every word to savor the meaning and balance of each sentence—it was a way to look at life as it passed.

Perhaps that’s why critics called him a “writer’s writer,” a label that annoyed him and, I suspect, everyone else. Jim’s friend, Bruce Jay Friedman, told a story about a weekly writers’ lunch he was part of in the Hamptons that included Mario Puzo (The Godfather), Joe Heller (Catch-22) and Mel Brooks (The Producers). The group was looking for a new member to liven things up but decided not to ask Salter because, as Puzo put it, Jim was “too good of a writer.”

If you’re an editor there is no such thing, but the implied problem with being a writer’s writer is that it goes with semi-obscurity and lack of commercial success. Not that Jim didn’t do fine; it was just so obvious that his talent outweighed his notoriety and his paydays. Of course Jim never talked about any of this. Then, in late 2012, with the novel All That Is, he was poised for the hit his talent had been promising for so many years.

Everyone who knew Jim was optimistic that the momentum was building, and he knew something was happening, too. “Oh, please,” he would say dismissively, but you could tell he was hopeful. There was a lot of press about All That Is, every piece noting that it had been more than 30 years since his last novel, Solo Faces, which Jim had written off of an unproduced screenplay he had done for Robert Redford based on the life of outlaw mountaineer Gary Hemming, who shot himself in Grand Teton National Park in 1969.

“The substitution of something right for something false can suddenly let light in on an entire chapter…”

I heard about Solo Faces when it was in galleys and knew a little about Hemming’s suicide and the climbing culture from editing Outside. Without reading a word of it, I got Jim’s number from Aspen information and called to ask about excerpting the new novel in Rocky Mountain, a new magazine I was launching out of Denver.

“Don’t you want to read it first?” Jim said.

“I don’t have to,” I said, and I’m sure Jim saw right through that. It would be a big deal for me to land James Salter for a regional start-up, and I had enough literary pretension to think I could edit him. I had no idea about his hundred combat missions as a fighter pilot or his 16 screenplays or his photographs of Rauschenberg and other artists or the eclectic mix of people he knew and the glamorous rooms he had moved through.

Thinking back, my call seems worse than impertinent, but on the phone that day Jim asked, almost patiently, if I knew anything about climbing. I told him its culture was rich like surfing’s but more intellectual, with more interesting new technology. I went on and, I’m afraid, on . . .

Jim heard me out and said he would sell me a piece but he was not remotely interested in being edited. Not even a comma, especially not even a comma, without checking with him. That was fine with me. I already had a hands-off policy when it came to excerpts and wrote thank-you notes suggesting that I was there only to get thorns out of paws. It was always satisfying to see how careful some writers were with pieces from their books. Cormac McCarthy once sent back a galley of my cut from All the Pretty Horses with a single comma circled as an intrusion—a copy editor’s change that I had not caught. Tom Wolfe would sometimes rewrite entire paragraphs if you asked him to look at one sentence. The best writers were always hard enough on themselves. Here is a paragraph of a letter from Jim to a friend of his, the writer and editor Robert Phelps, when he had finished polishing Solo Faces:

I mailed off the revised Solo Faces two days ago. Endless fretting and worrying about things that are at their best imperfect anyway. I added a chapter, changed the ending, and did innumerable small things throughout. It’s a bit better. It’s astonishing how the crossing out of a line, sometimes a phrase, or the substitution of something right for something false can suddenly let light in on an entire chapter. My typist accidentally left out seven lines at the end of Chapter 16 and I said, wonderful, it’s much better without them. I’m already ashamed of the first version.

I had not read that letter, of course, but when I did Jim’s characterization of the isometric relationships between the words he chose redefined him for me as a so-called writer’s writer. Maybe that’s what Mario Puzo meant, too.

Head here to read more writing advice from Terry McDonell.

__________________________________

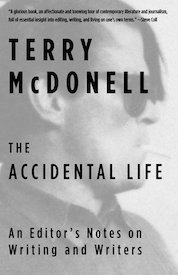

Adapted from The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers, by Terry McDonell (who is a cofounder of this website), published this month by Vintage. TerryMcDonell.com.

Terry McDonell

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is the author of The Accidental Life: A Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers and Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and co-founder of Literary Hub. TerryMcDonell.com