Snobs, Sophisticates, and Scathing Reviews in Wartime London

D.J. Taylor on Cyril Connolly Shepherd of "High Brow" Literature

To talk of “literary life” in the 1940s is faintly misleading. All that remains, three-quarters of a century later, is a number of different literary lives, of which the world inhabited by Cyril Connolly and his friends was only one—and that, some neutral observers would argue, not the most important or long-lasting. If the 1940s are the decade of Horizon, then they are also, in no particular order, the decade of neo-Romantic poetry, of Eliot’s Four Quartets, of dozens of crowd-pleasing middlebrow novelists such as Hugh Walpole and J. B. Priestley, whose books outsold anything that Connolly ever put his name to by a factor of fifty to one.

Occasionally these categories overlapped—both Walpole and Priestley contributed to Horizon’s opening number; Connolly, too, in his New Statesman reviewing days, had been an astute critic of such undemanding middle-of-the-road fiction as came his way. At other times, though, the gap between a metropolitan sophisticate and a provincial journeyman, between a bestselling novelist and a recherché little magazine poet, between the prescriptions of highbrow taste and the books with which ordinary readers beguiled themselves on trams and trolley-buses could show every sign of developing into an abyss.

We can see something of the myriad, differing constituencies which 1940s literature addressed by tracking George Orwell’s progress through the decade. The Horizon regular; the literary editor of the left-wing weekly Tribune; the BBC producer; the Manchester Evening News and Observer reviewer; the pamphleteer; the polemical columnist . . .

All these varying ports of call contributed something to the literary persona that he constructed for himself in the ten years before his death, and separating out the “real Orwell” from this routinely overstuffed workbook is impossible: no such thing exists, and the author of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four was as much at home lunching with a left-wing Labour MP—Michael Foot, say, with whom he enjoyed cordial relations—as chatting to Connolly about their time at prep school.

The same point could be made of Evelyn Waugh: happy enough to allow Connolly to shepherd his novella The Loved One into print in 1948, but eternally suspicious of the avant-garde artists and the translated foreigners that were a crucial part of the Horizon offering, more likely to be seen executing prestige commissions for Sunday newspapers or taking part in religious debates in the Catholic press.

As for what gave Connolly his power, his celebrity, his paralyzing influence on upper-brow taste in the 1940s, then the explanation was at least as much social as straightforwardly literary. Critics of the Connolly line—an increasing number as the decade proceeded—usually begin by asserting that in any enterprise to which he put his hand the aesthetic waters have been muddied by affiliations that are, essentially, located in class, that the boundary between the people Connolly printed in his magazine and the people with whom he dined and with whom he had been to school and university was faint to the point of invisibility.

We can see something of the myriad, differing constituencies which 1940s literature addressed by tracking George Orwell’s progress through the decade.

Certainly, Connolly’s circle at this time can seem horribly homogenous. Scarcely anyone who turned up, manuscript in hand, at the Horizon office or made his bow at one of Connolly’s parties had failed to attend a public school: Connolly, Watson, Orwell and Brian Howard were Etonians; Spender had been to Westminster; Quennell to Berkhamsted; Waugh to Lancing College. Most of them—Orwell was the exception—were Oxford graduates.

None of this made them upper class by the standards of the time—Waugh was a publisher’s son from Hampstead, Orwell’s father, Richard Blair, had retired from the Indian Civil Service on a pension of £600 p.a.—but it was a key factor in the almost imperceptible closing of ranks that sometimes distinguishes bygone literary life, the suspicion that a poet or a novelist or a short-story writer is being judged not by the quality of his metrics or the suppleness of his prose, but on whether or not he happens to be “one of us.”

The literary 40s are full of symbolic illustrations of this divide, of extraneous talent being welcomed into the exclusive palisades of Horizon or John Lehmann’s New Writing only to quail before some of the social assumptions on display. Shortly before her death in 1941, for example, Lehmann persuaded Virginia Woolf to allow him to print the text of a lecture entitled “The Leaning Tower,” given to the Brighton branch of the Workers’ Educational Association. Here the author of Mrs. Dalloway and The Waves spoke loftily of writers occupying “a raised chair,” of benefiting from gold and silver, of relishing their detachment from the workaday world: “to breed the kind of butterfly a writer is you must let him sun himself for three or four years at Oxbridge or Cambridge.”

The former miner B. L. Coombes, who complained of Woolf’s snobbery, was himself rebuked by Lehmann. To an Old Etonian, whose first job had been working as the Woolfs’ assistant at the Hogarth Press, inclusiveness could only go so far. Or there is the salutary tale of Sid Chaplin, another pitman with literary aspirations, encouraged by Orwell (who printed his stories in Tribune) and invited to call should he happen to be in London. Arriving at the very modest maisonette that Orwell shared with his wife Eileen in Kilburn, NW6, Chaplin discovered that a party was in progress on the other side of the front door. Unable to face the metropolitan sophisticates who lurked within, he turned on his heel and fled.

Thirty or even twenty years before, this kind of thing would have passed without comment. But there was a new kind of criticism beginning to establish itself, one less respectful of established reputations, more inclined to interrogate the social underpinning of the work brought before it. Q.D. Leavis—never afraid to name names—had already produced a pioneering essay entitled “The Background of 20th Century Letters,” in which Connolly’s Enemies of Promise and the memoirs of Logan Pearsall Smith, Edward Marsh and Louis MacNeice were glacially appraised.

The literary 1940s are full of symbolic illustrations of this divide, of extraneous talent being welcomed into the exclusive palisades of Horizon or John Lehmann’s New Writing.

How to obtain literary preferment in England? According to Mrs. Leavis, the “odious little spoilt boys of Mr Connolly’s schooldays move in a body up to the universities to become inane pretentious young men, and from there move into the literary quarters vacated by the last batch. Those who get the jobs are the most fashionable boys in the school, or those with feline charm, or a sensual mouth and long eyelashes.”

What gives this assault its kick to anyone in the know is the fact that the final phrases are a direct quotation from Connolly’s account of Brian Howard in his Eton pomp. “The advantages Americans enjoy in having no Public School system, no ancient universities etc., can hardly be exaggerated,” she crossly concludes.

Even more than Connolly, Brian Howard (1905–58) would come to be regarded as the villain of the piece, the self-regarding flibbertigibbet whose spectacular lack of success seemed not to have occurred to his well-placed friends, endlessly cosseted and indulged in the hope that he might someday write the masterpiece of which everybody assumed him to be capable. “Today the gentlemen are on the defensive,” Connolly’s old adversary Julian Symons wrote in 1972, “but there are still reasons for being miffed about (to take a small instance) the seriousness with which a book about the talentless Brian Howard, talentless perhaps but amusing, and one of us, was recently treated.”

The book in question was Marie-Jaqueline Lancaster’s Brian Howard: Portrait of a Failure (1968), a remorseless 600-page compendium of narcissistic play-acting and serial non-achievement, and, as Symons points out, respectfully received by many a newspaper arts critic.

It was Connolly himself who came up with the adjective that still tends to attach itself to the style that he and his friends championed in the era of the Blitz, the Normandy landings and the Attlee government: “mandarin,” which to a Leavisite would have meant detached, ironic and de haut en bas. Come the 1950s, the epoch of Angry Young Men, of “Movements” and grammar-school boys on the make, the mandarins would be in sharp retreat, driven back by the provincial, middle-class tide that produced novels like Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim (1954) or Malcolm Bradbury’s Eating People is Wrong (1959).

A decade later, they were museum pieces. But here in the 1940s, Connolly was a genuine literary power-broker, a grand panjandrum, a maker—and breaker—of reputations.

__________________________________

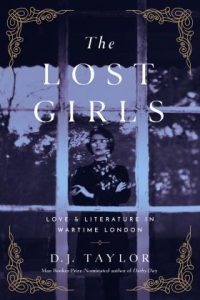

Excerpted from The Lost Girls: Love and Literature in Wartime London. Used with the permission of the publisher, Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2020 by D.J. Taylor. Pictured above Jean Bakewell, Angela Culme-Seymour, Cyril Connolly, and Janetta Woolley.

D.J. Taylor

D. J. Taylor is a novelist, critic ,and biographer whose Orwell won the Whitbread Prize for Biography. His most recent books are The Lost Girls; Kept; Bright Young People: The Rise and Fall of a Generation; Ask Alice; and Derby Day, which was nominated for the Booker Prize and was selected as a Washington Post Best Book of the Year.