Shaping Hunger Into Practice: On the Creative Relationship Between Writers and Visual Artists

Sally Cabot Gunning Talks Painting the Light and Books that Spotlight Women Artists

My latest novel, Painting the Light, takes place on the island of Martha’s Vineyard in the year 1898. Around this time women artists coming out of the Boston School were beginning to gain critical and financial success; it had been no walk on the Boston Common to gain the proper training, as women weren’t allowed to paint nudes, and sculptor Anne Whitney was denied a prize because it was considered improper for a woman to sculpt a man’s legs—through his trousers.

My protagonist, Ida Pease, is one of these artists, having reached a level of success as a portraitist for high-society Boston. But an impulsive marriage lands Ida on a sheep farm on Martha’s Vineyard, and now, if she wishes to resurrect her career, Ida must learn to paint something else. So in order to climb effectively into Ida’s shoes, I revived my own dormant interest in art; I signed up for painting classes with Odin Kaeselau Smith at the Cape Cod Art Center. Living near the sea as I do, much of my painting had featured water, sky, marsh. Teaching Ida to paint the sea around her wasn’t that much of a stretch, but those sheep were problematic. Ida wants to paint those sheep, so I want to paint those sheep. I arrived in class with a huge envelope full of gorgeous watery, grassy, hilly fields of sheep, of barns full of newborn lambs, of ancient stone walls, and centuries-old farmhouses.

Odin was more than up to the task, as it so happens she has all kinds of farm animals. “When painting animals, think circles,” she said. “One for the body, one for the head.” And then, “Add the corners.” So that was the first thing I learned about painting sheep: they had corners. I ran along on a happy parallel track as I wrote during the day and took art classes at night, attempting to capture that luminous Vineyard light in class just as Ida was doing on the page, attempting those troublesome not-round, not-square sheep. I could look through Ida’s eyes and have her look through mine as we learned to paint, as William Morris Hunt, one of the first to open classes to women, taught them: don’t paint things as they are; paint them as they seem.

But as I wrote and painted and wrote I began to ponder that curious link between the two creative processes. So many writers paint; so many painters write. What explains this frequent crossover? Is it just that the urge to create is so strong it spills out wherever it finds an outlet? Or is it the urge to solve the puzzle, whether with word or color or form or light? And is that why so many writers choose to write about artists?

*

Robin Oliveira, I Always Loved You

In I Always Loved You by Robin Oliveira, a novel that delves into the relationship between Mary Cassatt and Degas, there is a wonderful passage that addresses exactly that. Mary Cassatt has struggled in the shadow of Degas, but then she—or rather Oliveira—writes this: “Mary had become the artist she had wanted to be by dint of hard work and perseverance. And what was left was work, the work she had chosen; the pleasure of the puzzle, [emphasis mine] the technical questions of execution, the choice of composition and color, nothing different than before except that now she understood that pain was the foundation of art—not always its subject, but always its process… But no longer did she fear it meant failure. She knew she would succeed eventually with a canvas… She knew that she would find its soul.” Most of the good writers I know could have written that passage.

Whitney Scharer, The Age of Light

Since I’d once dabbled in photography (I turned what was supposed to be a laundry room into a darkroom, papering the room’s unfinished walls and ceilings with the imperfect black and white images that came out of the developing tray), I related strongly to The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer. Set in Paris during the Golden Age, the book revisits the career of former Vogue model Lee Miller and her personal and professional relationship with the famous artist/photographer Man Ray. Here is how Scharer describes the moment when Miller realizes she wants to be a photographer, not just the muse/model of a photographer: “Looking at those small black and white images, conjured not only from her mind but from a unique combination of light and time, Lee filled with an excitement she never felt when painting. She had released the shutter, and where nothing had existed, suddenly there was art.” Take it from someone who still prefers darkroom over laundry room—it doesn’t get better than that.

B.A. Shapiro, The Art Forger

The Art Forger by B.A. Shapiro was of particular interest to this Massachusetts girl because it references the great heist at Boston’s renowned Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Shapiro’s classic struggling artist makes a deal with the devil to create a forgery of a stolen Degas in exchange for a one-woman show, but is the stolen “Degas” really another forgery? She sets out to study Degas’s work in an effort to solve that puzzle, and here’s how Shapiro describes her character’s awe in the presence of the great works: “The way he creates light from within and without, faces glowing with life where there is only canvas and paint. The way he captures movement with the tilt of a head or the hem of a dress drifting off the edge of the canvas. His use of dark and light values to create texture, depth, and shadow.” The pieces of Shapiro’s puzzle—how to forge a Degas— begin to fall into place as she discovers anew what makes great art. Shapiro, it turns out, is a serious student of art.

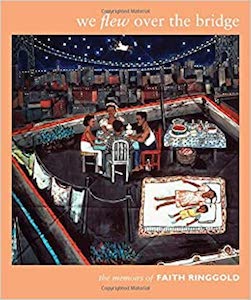

Faith Ringgold, We Flew Over the Bridge

With Faith Ringgold I came at the crossover theme from the other direction, starting with the artist and then moving on to the writer. Ringgold is an African American artist who came out of the Harlem Renaissance, but when she hadn’t had an exhibit in ten years, when no one would publish an autobiography she wrote, she turned to performance art and to telling her story in quilts. “I wanted very much to be heard,” she said. Uniquely, her first story quilts were just that—painted quilts that incorporated text into the images—but heavily influenced by a mother and grandmother who taught her to quilt in the African tradition, learning from the African palette, her story quilts became vibrant and historical works of art. Eventually, Ringgold’s autobiography was published, and she also authored a series of acclaimed children’s books.

Celeste Ng, Little Fires Everywhere

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng, a first-generation Chinese American, takes its own unique look at the world of art, and again with photography. Ng was another author with an artistic background—she’d once dabbled, if I dare use that word in her behalf, in clay miniatures, and was no stranger to the multi-dimensional creative process. In Little Fires, her artist, Mia, photographs scenes and images and then amends them with paint and numerous collage-type techniques. Her description of the pull of this work might just hold another key to the artist/author link: “The photos stirred feelings she couldn’t quite frame in words and this, she decided, must mean they were true works of art.” Do words sometimes fail the writer? Do images sometimes fail the artist? Is this what causes them to venture out into that other dimension? Even more fascinating, writing Little Fires Everywhere brought Celeste Ng to take up photography for herself, completing the circle.

Dawn Tripp, Georgia

Dawn Tripp’s novel Georgia, about Georgia O’Keeffe, is my favorite book about an artist. After reading Georgia I reached out to Dawn to ask a question I already knew the answer to just by reading her beautiful prose: did she ever paint? Yes, she did. (Now she’s a photographer). I can think of no one who combines gorgeous prose and gorgeous art as well as Tripp. Her novel delves into O’Keeffe’s process of becoming, her struggle to dig herself out from under the creation her famous photographer husband, Alfred Stieglitz, tries to make of her. Reminiscent of Lee and Man, Stieglitz sparks his own career with nude photographic portraits of O’Keeffe, nearly derailing O’Keeffe’s own career in the process. The storyline itself is fascinating and deeply sensual, but what I love most is the way Tripp captures the equally sensual process as Georgia creates her art: “I dip my brush into a bowl of water, then swirl it through red paint—that quick thrill of the first mark of color on blank paper, the brush’s point to cut that outer edge, the petals opening, their redness thinned in places, pale sunlight shining through.” And then there’s this: “All I am really trying to do is say something that I feel in color and form, something that matters, something that has life… When I make a picture of a flower, I don’t paint it as I see it, but as its essence moves me. I eliminate every detail that’s extraneous. I paint it as I want it to be felt.” In other words, she paints it as it seems.

Raven Leilani, Luster

In Luster by Raven Leilani, the exploration of an artist who has lost her ability to paint is only one manifestation of several intense themes—race, self-realization, the complexity of human relationships whether healthy or not —but all is intertwined with such skill (and wit) that I had to pause more than once just to admire the weave. Once again, the way Leilani wrote about art told me she was a practitioner even before I read the thank you in the acknowledgments to the person who gave her her first sketch pad, and there are many passages I could quote to illustrate the artist/writer connection, but I believe this says it best: “I think about… all the raw materials that are gathered and processed into shadow and light. The pigments drawn from sand, and Canterbury bells, the carbon black drawn from fire and spread onto slick cave walls. A way is always made to document how we manage to survive, or in some cases, how we don’t. So I’ve tried to reproduce an inscrutable thing. I’ve made my own hunger into a practice, made everyone who passes through my life subject to a close and inappropriate reading that occasionally finds its way, often insufficiently, into paint.” Whenever I’m asked which character in one of my books is most me, I reply—all of them. Everything I’ve ever read or seen or heard or felt ends up in some character in some small or large way, so this passage resonated.

But here’s the funny thing—as I sat down to proof this piece I saw that in the third to last sentence I’d mistakenly typed the word print instead of paint. I guess that says it.

__________________________________

Painting the Light is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Sally Cabot Gunning.