Sometimes I teach old books to young people, and recently I was teaching the Epistles of the Roman poet Horace to a group of undergraduates. For many centuries there were few authors more widely read than Horace, though to be fair most of the readers were boys forced to translate him from Latin when they would far rather have been playing some kind of ball game. Some old dude sitting in a farmhouse writing rhythmical letters to friends— this was not exactly a recipe for delight.

Maybe my students—mostly young women, these days—also thought they had better things to do. But then we got to one of the Epistles, addressed to one Lollius Maximus, in which Horace wonders how one might acquire “a tranquil mind.”

A tranquil mind. Who doesn’t need that? Often at the beginning of a class I will give my students a brief reading quiz—unannounced in advance; yes, I’m that kind of teacher—which has the salutary effect of making sure that everyone is in class on time. The room is always full when I walk in, and fairly regularly the first thing I see is every head bowed before a glowing screen. Sometimes they don’t even look up when I say hello. Often their brows are furrowed; they may look anxious or worried. They dutifully put their phones away as soon as class begins, whether it does so with a quiz or a question, but during the discussion I occasionally see hands twitch or reach toward bags. If I see phones left on the seminar-room table I lightly (but seriously) suggest that they be put away to minimize temptation. All my students have mastered the art of packing up their bags at the end of class with one hand while checking messages with the other. They leave the room with heads once more down, and brows once more furrowed, navigating like a blind person through her familiar living room.

I know how they feel. When my students are taking a quiz there’s nothing for me to do, so my hand then drifts toward my phone—or did, until I finally forced myself to stop carrying my phone around; and my twitchiness during quizzes was among the chief factors that pushed me to that decision. That twitchiness—that constant low-level anxiety at being communicatively unstimulated—seems so normal now that we may be slightly disconcerted when it’s absent. That’s why a tweet by Jason Gay, a writer for The Wall Street Journal, went viral a few years ago: “There’s a guy in this coffee shop sitting at a table, not on his phone, not on a laptop, just drinking coffee, like a psychopath.” A man not justifying his existence through constant work or constant social connectivity? Psychopathy seems the only logical explanation. Unless, of course, he happens to possess a tranquil mind.

The old man in an Italian farmhouse, two thousand years ago, thought a lot about how you might acquire such a mind. “What brings tranquility?” he asks his friend Lollius Maximus, or rather muses to Lollius. “What makes you care less?” What did Horace need to “care less” about? It’s worth taking a moment to tell his story. His father had probably been born a slave; certainly he had spent some time in slavery. Eventually he was able to purchase his freedom and made a career that allowed him to offer his gifted son (born 65 BCE) the best education on offer, including a period at the great Academy in Athens that had been founded by Plato. Later Horace was both a soldier—a very bad one, he said—and a political activist, though unfortunately for him he was active in opposition to Octavian, who would become Augustus Caesar. He had his property confiscated and fell into poverty; he began writing poetry; his poetry came to the attention of a powerful politician and ally of Octavian named Maecenas; Maecenas became Horace’s patron and bought him a farm in the Sabine countryside.

And that’s how he came to sit in a farmhouse to contemplate just what it is that gives you a tranquil mind. He had been plucked from the complex and overlapping dangers of a politically engaged person in Rome during a period of intermittent civil war, and set down in the peaceful countryside. And yet his mind continually twitched toward that mad world he had fled from; because, after all, all roads lead to Rome. Rome is where the action is: the festive dinners that collapsed into political argument, the drinking parties that served as cover for conspiracy, the fortuitous encounters in the streets that led to the whispered exchange of gossip…. You were always in danger in Rome; but you were always connected. In the country nothing happened—unless it happened in your mind.

Horace thinks and thinks and thinks about these things, and writes his letters that are also poems to far-flung friends—letters, therefore, that are also meant for strangers. And so we strangers to Horace and strangers to Rome, fifteen people sitting in an air-conditioned room in central Texas, a place Horace could never have imagined, sat with his poems before us and realized that we wanted to know exactly what Horace wanted to know, and for many of the same reasons. We wanted tranquil minds. We wanted to escape our addiction to the adrenaline rush of connectivity. When Horace advises Lollius Maximus he also advises himself—indeed, the poem may do the latter more than the former. “Interrogate the writings of the wise,” he counsels.

Asking them to tell you how you can

Get through your life in a peaceable tranquil way.

Will it be greed, that always feels poverty-stricken,

That harasses and torments you all your days?

Will it be hope and fear about trivial things,

In anxious alternation in your mind?

Where is it virtue comes from, is it from books?

Or is it a gift from Nature that can’t be learned?

What is the way to become a friend to yourself?

What brings tranquility?

What makes you care less?

(I am using David Ferry’s marvelous translation.) Horace exhorts himself, and us, to “interrogate the writings of the wise”—the sorts of thinkers, perhaps, that he studied when he was at the Academy in Athens—because they are wise, of course, but for another reason as well: they are alien to us, they are not part of our habitual round. They draw us out of our daily, our endlessly cyclical, obsessions with money and with “trivial things”—the kinds of obsessions that “harass” us, that “torment” us, that make us jump from thought to thought, or rather emotion to emotion, in “anxious alternation.”

It’s useful to see that these anxieties have plagued people who lived so long ago, even if we feel them with particular intensity today—as we probably do. One of the consequences of an individualist society such as ours, a society in which each of us is expected to forge her own identity according to her own lights, is that we feel what the sociologist Norbert Elias called “pressure for foresight,” the compulsion (perhaps a better translation of Elias’s German) to look ahead into a future for which we must plan, but which— the future being the future—we cannot see. That is why some therapists who work with young people today say that the single greatest source of stress and anxiety for them is the sheer number of choices they have before them, which generates the fear that if they make the wrong choices they may not be able to overcome their own errors. And my long experience as a teacher confirms this interpretation.

Horace exhorts Lollius, exhorts himself, exhorts us, to shift our attention from those compulsions toward questions that really and always matter—“Where is it virtue comes from?”—because even by just exploring those questions, even if we fail to answer them, we’re pushing back against the tyranny of everyday anxieties. We’re resisting, or evading, the stresses that a condition of always-on connectivity inevitably brings to us, in large part because when we are so connected we are constantly driven to compare ourselves to others who have made better choices than we have. (Or so we think, forgetting that Instagram is a great deceiver in these matters.)

To read old books is to get an education in possibility for next to nothing.You can tell that Horace was a convivial sort. Living a life of simple silent contemplation (“like a psychopath”) wasn’t for him. But he knew also that the life of politically obsessed Rome was dangerous to him in more ways than one. Even when he wasn’t in danger of being imprisoned or killed for being a rebel, he was in danger of having his mind colonized by anxieties large and small. He therefore sought to receive his Sabine farm as a refuge, as a place where he could walk down by the tree- shaded brook, and enjoy the local wine; where he could return to his house and write long intricate letters to friends; where he could “interrogate the writings of the wise.” The past became a companion to him in what otherwise might have felt an exile, because, as L. P. Hartley famously says at the outset of his novel The Go-Between, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” Which of course doesn’t mean that what “they do” is always right— but awareness of it is always illuminating, and often liberating.

We sat in our Texas classroom and thought about this. Horace reached out from long ago and far away to tell us that we should ourselves reach out to the long ago and far away. He was not like us; and yet he spoke to us health-giving words. That he was not like us—that he spoke from a world whose contours made it so different from ours—made those words somehow easier to receive.

My students and I were reflecting on the current of our own daily lives, which is not an insignificant thing to think about; but the past can touch us and teach us unexpectedly in matters of broader import. In 2016, the Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh published a nonfiction book called The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. One of the themes of the book is the relative absence of climate change in contemporary fiction: it is strange, Ghosh thought, that our storytellers could be so silent about events that are so enormously consequential for the entire planet. And as he tried to write his own novel confronting climate change, he found few resources to help him among his fellow writers today. Yes, there is a small subgenre of climate fiction, “cli-fi,” as it is sometimes called; but it tends to look predictively or dystopically toward the future. How do we reckon with the experience of now?

Ghosh told the journalist Wen Stephenson about a realization that, as he asked that question, came to him: “You know, after I finished writing The Great Derangement, I felt that to look to late-twentieth-century literature for any form of response to what we are facing today is useless. It offers no resources. It’s so much centered on the individual, so much centered on identity, it really doesn’t give us any way of thinking about these issues.” So what, then, to do, if you’re a writer who is craving some kind of model or example for creative engagement with such massive forces? “I decided that… I must go back and read pre-modern literature. And I’m fortunate that I can read pre-modern Bengali literature.” And as he started reading these old, old tales from his own cultural past, he was surprised: “So I started reading these stories, and you know, it’s really remarkable how aware they are, how responsive they are to catastrophe, disaster, to the stuff that’s happening around them, even though it’s not at all in a realist vein. But it’s there. It’s omnipresent.” It was from his ancestors, not from his contemporaries, that he learned how to think about the experience of living through environmental changes so massive that they dwarf human imagination.

Ghosh concluded that reading works from the past “really teaches you that what has happened, what modernity has done is, literally, made this work of recognition impossible.” That is, modern consciousness has taken certain forms that don’t just ignore the experiences that he wants to write about but disable us from understanding them. But modern consciousness is not all we have to draw upon.

To read old books is to get an education in possibility for next to nothing. Watching the latest social-media war break out, I often recall Grace Kelly’s character in High Noon, a Quaker pacifist, saying, “I don’t care who’s right or who’s wrong. There’s got to be some better way for people to live.” (That by the end of the movie she abandons her pacifism only, if ironically, emphasizes the importance of her point.) The suspicion that there’s got to be some better way for people to live has the salutary effect of suppressing reflex. To open yourself to the past is to make yourself less vulnerable to the cruelties of descending in tweeted wrath on a young woman whose clothing you disapprove of, or firing an employee because of a tweet you didn’t take time to understand, or responding to climate change either by ignoring it or by indulging in impotent rage. You realize that you need not obey the impulses of this moment—which, it is fair to say, never tend to produce a tranquil mind.

_________________________________________________

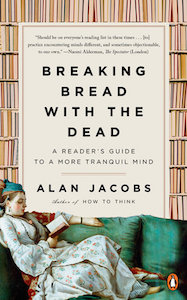

From BREAKING BREAD WITH THE DEAD by ALAN JACOBS, to be published by PENGUIN BOOKS, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Claimant.