Searching for a 14th-Century Scribe in Modern Jordan

"The stereotypes of the region exist in new forms"

The night, Shihab al-din al-Nuwayri writes, is divided into twelve hours, “each with its own name given to it by the Bedouin Arabs”—sunset (shāhid), dusk (ghasaq), darkness (atma), blackness (fahma), the enfeebling hour (mawhin), midnight (qit), the heart of the night (jawshan), the disgracing hour (hutka), the foretokens of morning (tabāshīr), the first dawn (al-fajr al-awwal), the second dawn (al-fajr al-thānī), the widespread dawn (al-mutarid).

It is somewhere between jawshan and hutka, the heart of the night and the disgracing hour, that I find myself walking down a street in Amman, having committed what al-Nuwayri declares the “mother of all crimes”—imbibing wine. I ponder whether my favorite downtown restaurant is open at the disgracing hour; craving the comfort of carbs, a ritual that plays out in all the great capitals of the world on weekend nights. I consider asking the cab driver I flagged down for a cigarette, but he is too busy speeding, talking too fast on his phone, smoking, to pay his passenger any attention.

Al-Nuwayri’s admonishment is clear: I must ensconce myself in my house, only emerging when the drunkenness has receded. It is sound advice, emerging all the way from the 14th century, when the Mamluk empire scholar Shihab al-din al-Nuwaryi began writing a compendium of the world. He produced a poetic, expansive encyclopedia that spanned 33 volumes, which once lined libraries and was delved into for the answers that plague one’s thoughts from the widespread dawn until sunset.

Over seven centuries later, these learnings have been replaced by Google; his anecdotes and accounts by tweetstorms and the Snapchat-sized reflections that light up mobile screens across Amman. But al-Nuwayri’s observations and contradictions still hold. His volumes combine magical realism and scripture to present a view of the world in all its horror and beauty, with stereotypes and myths and legends, tinged with subservience to a higher order.

In his abridged, lyrical translation of al-Nuwayri’s compendium—The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition—the scholar Elias Muhanna offers a selection of the scribe’s work; comprising everything from quotes from Islamic texts and anecdotes from the life of the Prophet Muhammad to romanticized facts, tales, and urban legends.

Al-Nuwayri’s volumes serve as a guide to the world; in this ensconced valley in the Middle East, I use his words as a guide to Amman, the capital of Jordan.

The Jordan Valley, in al-Nuwayri’s recollections, is a place where men grapple with fearsome lions. But in the cafes that line Amman’s streets, people are grappling instead with introspective questions. Over glasses of wine and running cab meters emerge the issues of identity, the risks of radicalization, the realization that religious conservatism isn’t just some kind of fringe idea, and the reality of a war that is sending refugees, once again, to Jordan and beyond. The fear isn’t one person, or a lion, or a mythical beast: it is ideas, war, conflict, the fear of the “other,” the fear of falling into a pit of comfortable complacency.

Guidebooks and newspapers rave excitedly about these “contrasts” in Jordan, often described as the safest place in the most dangerous neighborhood. The latest news, in the month that I arrive in Amman, is that there is a brewery in the Holy Land, reported with the wide-eyed wonder that alcohol can co-exist with religion in Jordan. The subtext is always clear: how do these deeply religious people in a deeply religious place in the world drink, as if the other major religions of the world don’t bar or frown upon their adherents from committing crimes as if people haven’t penned odes to liquor for centuries?

These contrasts and contradictions are not new. As Muhanna’s rendition of al-Nuwayri’s volumes show, these contrasts have always been a part of this uncomfortable, unsettled co-existence. It is summed up by the pithy sign put up by a bar in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood to advertise its special for Eid, the Islamic celebration marking the end of the annual pilgrimage to Mecca: “Happy Eid and Shots Night.”

These contradictions play out in Amman in ways small, unspoken, or protested noisily. On a Friday night—Amman’s Roman amphitheater—is silent. The Lebanese band Mashro’u Leila wasn’t allowed to perform this year at the amphitheater, assumedly because its lead singer is gay. The decision was reversed, mimicking how Al-Nuwayri’s volumes are typically contrarian on the topic. He lists the religiously mandated punishments for sodomy—usually equated with homosexuality in Islamic scripture and teachings—and on the next few pages, he quotes sexually charged poems:

“He embraces me until morning

Trading stories until dark.”

The music of Mashro’u Leila is still found on Facebook pages where their fans in Jordan posted songs in the act of virtual support. The “stories until dark” play out in other places in Amman; in private, at homes, and online, where men and women meet each other. But, in equal measure, they will condemn each other for their sexual choices, just as they will condemn an act that stands against everything they believe in.

One morning, Amman wakes up to the news that a writer accused of disrespecting Islam has been shot dead outside a court. The newspapers report there is a gag order against discussing the case, even as Facebook and Twitter erupt with conjecture and condemnation, and with people condoning the murder. A number of people who supported the assassin are detained. A group of protestors argues for free speech on the streets of Amman. Days later, they are replaced by protestors with new causes: political, social, and religious. One day, it is a gas deal with Israel. The next week, it is the place—or lack—of religion in school textbooks.

The protests fade away by the evening. In the center of the city, the lights shine down on the sole grassy expanse in Amman. The spotlight is not on gladiators, lions, or fighters but the female footballers of the under-17 World Cup being held in the city. The newspapers profile the young Jordanian footballers, their struggle, how they’re setting an example, turning them into cultural figures. In a store window, two other icons peer out: life-size cardboard replicas of the royal stars of the Ottoman-era themed soap opera from Turkey, that became a sensational success in the region and beyond over the last decade.

Elsewhere in the city, under the dim lights of smoke-filled cafes, young love plays out, a retelling of al-Nuwayri’s vision of the world: “And bordering the Slavs are two islands: one of them is called the Amazonian Island of the Women, and it is inhabited only by women. The other one is called the Amazonian Island of the Men, and it is only inhabited by men. Every year, they come together during the spring, copulate for about a month, and then part.” In Jordan, this is wedding season: the time of the year when families spend tens of thousands of dollars on elaborate wedding receptions, and then in a few months, or years, the couples part, sending the divorce rate spiraling upwards, and people back to their distant, Amazonian islands.

By morning, the debates and protests and identity crises are replaced with the humdrum of work, with the cabs filling the streets and railing against Uber and Careem. Amman greets the day with the morning prayers; the orchestra of muezzins reciting the morning call to prayer, rousing the faithful as the dawn slips in between the slats of blackout shades.

And then there is the sound of the other kind of faithful: fans of the legendary Lebanese singer Fairouz, broadcasting her odes to the morning from their car stereos and cell phones, an unspoken ritual passed on from generation to generation. Her voice combines with the church bells ringing out from the neighborhoods where crosses peek out from between houses and in diamanté crusted forms around the necks of women, and the shops where the day begins with blaring recitations of the Qur’an before traders start selling coffee as thick as syrup. It is this symbolic diversity that Amman seems to pride itself on, that it has enjoyed even as multicultural societies around it—Syria, Iraq, and Egypt—are in various states of conflict and chaos.

The stereotypes of the region exist in new forms; the lands that were once heralded as bastions of civilization are now being decimated. As al-Nuwayri quotes, when the world was created, the virtues and vices went off to the world: Courage went to Syria, as well as Discord. Poverty went off to the desert and “Misfortune said, ‘I’m coming with you.’”

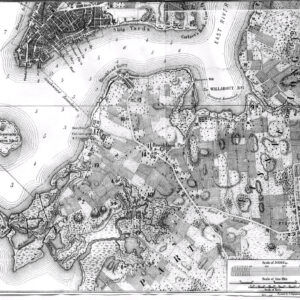

Jordan forms the starkest contrast of them. It is the country that survives, that staves off discord amid the dust that al-Nuwayri poetically elucidates: “Al-naq wa-l-aqūb is the dust that swirls around the hooves of horses and camels. Al-aj ā j is dust stirred up by the wind. Al-rahaj wa-’l-qas t al is the dust of war; al-khaydaa, the dust of a battle. Al-ithyar, the dust of feet.”

In Amman, the dust of war and battle flies around the Abdali neighborhood, where buses and cabs once careened off to Damascus around the hour. The travel offices are quiet, the chaos replaced by the nothingness that speaks louder. The dust floats among the couples sitting on the benches on the street, quietly conversing. The dust floats past the new restaurants that proudly declare themselves to be originally Syrian; a sign to the refugees who have fled misfortune and arrived in Amman. The dust of feet circles outside the visa queues, or in the government building where a statuesque woman argues with an official and then draws herself up and begins to cry, stifling her sobs with her fist. The dust of the wind swirls from the charcoal burning atop the hookahs in every cafe and on every street corner, melding with the dust from Palestine and Syria and Iraq, where people have streamed into Jordan from over the last seven decades.

It is the dust that keeps drawing people in—refugees, expats, tourists, writers, development workers—all drawn in by the opportunities that the dust provides, trying to chronicle and coach their way through the region, and to write compendiums, to call a part of this city’s sandstone-hued skyline their own. The last time I was in Amman, I was in my early twenties, on the verge of choosing a life of writing, unsure of a future ahead. I return to Jordan while in my early thirties, still unsure of the future ahead, looking for signs from my past and from al-Nuwayri’s ancient vision of the world. But as he writes: “the soul, after all, cannot bear continuous labor and finds a change in affairs to be pleasing.” And so, I am back in Amman, wondering whether I will ever be part of the dust, or am destined to observe it from the window of a careening cab.

Saba Imtiaz

Saba Imtiaz is a freelance journalist currently based in the Middle East. She writes about culture, food, urban life, and religion. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian, and Roads and Kingdoms. She is the author of the novel Karachi, You’re Killing Me! (Penguin Random House India, 2014), and is working on a non-fiction book titled No Team of Angels – Murder, Violence and Land in Pakistan’s Largest City: Karachi (First Draft Publishing).