Science: You’re Definitely Worrying About the Wrong Things

How Much Should We Worry About an Asteroid Strike? Sugar? Fluoride?

Three Things That You Really Don’t Need to Worry About

(according to the Worry Index*)

Fluoride

In small doses, fluoride is good for your teeth. It protects against tooth decay by binding to the enamel (the hard, outer shell of the tooth) and remineralizing the enamel with calcium and phosphate. This makes the enamel harder and more resistant to bacteria. For this reason, most toothpastes contain fluoride, and dentists apply topical fluoride treatments to their patients’ teeth, and many communities add fluoride to their water supplies.

Grand Rapids, Michigan, was the first city in the world to add fluoride to community drinking water as part of a pilot program to see if it would reduce the incidence of tooth decay. It did, by up to 50% compared to control communities where fluoride was not added to the water. This result has been replicated many times in different studies and in different parts of the world. The evidence is clear: fluoride protects against dental caries (cavities). Because of this, community water fluoridation is common all over the world, although some cities, like Portland, Oregon, have consistently refused to participate.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists water fluoridation as one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century. Several pages of the CDC’s website are devoted to reassuring the public that fluoridation is safe and healthy.

But some people are not reassured. Water fluoridation was controversial when it was introduced and remains controversial today. Critics claim that fluoride in drinking water causes myriad health problems including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, lowered IQ, thyroid problems, digestive complaints, and bone fractures. In the more than 70 years since water fluoridation was introduced, these concerns have waxed, waned, and changed, but never disappeared.

Fluoride is an inorganic anion, which means that it doesn’t contain carbon and it has a negative charge (calcium and phosphate are also inorganic ions, although they carry a positive charge). Fluoride occurs naturally in the environment, including rocks, dirt, and seawater. In many places, high concentrations of fluoride exist naturally in the water. This is, in fact, how the dental protective effect of fluoride was discovered. In the early 1900s, a Colorado dentist noticed that the children in Colorado Springs had some really ugly teeth. Specifically, children that were born in the area, or who moved there when they were young, developed permanent teeth that were pitted and stained dark brown (like chocolate). But in addition to being unattractive, these teeth were curiously resistant to decay.

The culprit turned out to be (surprise!) fluoride, which was present in high concentrations in the local water supply. The condition, originally called Colorado brown stain, was subsequently renamed fluorosis. Consumption of very high levels of fluoride can lead to skeletal fluorosis, a painful and debilitating joint condition. Fluoride can also be acutely toxic in high doses, which is why you should call poison control if your kid eats a tube of fluoride toothpaste.

Debilitating disease and acute toxicity are clearly undesirable, which is why the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set the upper limit for how much fluoride can be in drinking water at 4 parts per million (ppm). But the existence of an upper limit is not in itself cause for alarm. Dosage is an important factor. Many things that are good for us in small doses are bad for us in large doses. Iron is a good example of this. If you don’t get enough iron, you will be anemic; if you take too much, it will kill you. The same is true of vitamins A, D, E, C, and K. Even too much water is lethal. The fact that fluoride has negative consequences in large doses is not unusual and shouldn’t disqualify its use in any form.

One notable difference between fluoride and the vitamins and minerals listed above is that fluoride is not known to be necessary for human health. It is, however, helpful (again, like a lot of things). Low doses of fluoride reduce the incidence of tooth decay without causing fluorosis. Artificial fluoridation of water is targeted at the sweet spot where there is an observable benefit but minimal (ideally zero) side effects (slight cosmetic fluorosis is considered acceptable).

Many people don’t believe that such a sweet spot exists, but scientific consensus says that it does. This does not mean that there has been no legitimate dissent. Because fluoridation has been around for a long time, there is a fair bit of epidemiological data to look at, which is good in terms of assessing health outcomes. Numerous studies in animals have also tested the effects of fluoride. However, care is required when evaluating this scientific literature because there is a fair bit of pseudoscience (or straight-up bad science) mixed in with the real thing. Some studies link fluoride consumption to bone cancers, lowered IQ, ADHD, and hypothyroidism.

However, these studies have suffered from methodological concerns such as small sample sizes and improper controls. These critiques may sound trivial, but these issues can lead to false conclusions. For example, if the water that has high fluoride concentrations also has high lead concentrations, you might misidentify the problem. Therefore, it is important to interpret these studies as part of the entire corpus of scientific evidence.

The National Academy of Sciences has conducted several reviews of fluoride. In a 2006 report on the EPA’s standards for fluoride in drinking water (“Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA’s Standards”), the reviewing committee identified severe dental fluorosis as the critical end point of concern (the problem that will develop at the lowest dose that is likely to cause a problem). The committee found that the EPA’s upper bound of 4 ppm was too high to prevent this problem and, further, it was probably too high to protect against bone fractures. In other words, their opinion was that the maximum allowed concentration should be lower.

For reference, this upper limit was (and still is) 4 ppm, and the recommended range for artificial fluoridation is only 0.7 ppm. The committee did not address artificial water fluoridation because that is not within the purview of the EPA. The committee also reviewed the effects of fluoride on other body systems including reproduction and development, neurotoxicity and behavior, the endocrine system, genotoxicity, and cancer. They identified cancer and endocrine effects as potential areas of concern and recommended that the EPA keep an eye on them.

The EPA published a 6-year review (“Six-Year Review 3—Health Effects Assessment for Existing Chemical and Radionuclide National Primary Drinking Water Regulations—Summary Report”) in December 2016. The report covered all of the chemicals (and radionuclides) that are found in water supplies, but included an entire appendix about fluoride. The EPA did review the emerging literature on cancer effects; follow-up studies showed that there weren’t any effects (in bone cancers).

They also reviewed the study linking fluoride to hypothyroidism, but concluded that it did not properly control for several variables. The EPA also studied the data for other health concerns, but did not find anything alarming enough to suggest a revision to the existing upper limit for fluoride concentrations in water. The EPA acknowledges that lowering the limit has the potential to improve health, but fluoride is a low priority compared to other issues, and they do not want to divide their resources. In other words, there are bigger problems with drinking water that you should probably be worried about instead.

For its part, the U. S. Public Health Service, which sets the recommendation for artificial fluoridation levels, revised its fluoride numbers down from 0.7–1.2 ppm to 0.7 ppm in 2015. This is because people are exposed to more fluoride now than they were in the mid-20th century when the original recommendation was made.

If you’re on the fence about fluoride, it is worth pointing out that while we tend to think of cavities as unpleasant, we don’t usually think of them as such a big deal. This might be because, as a society, we do not get as many cavities as we used to. But cavities can be incredibly painful. Left untreated, they can even kill you. Most of us wouldn’t leave cavities untreated if we could afford to do something about it. And that’s the crux of the issue. Not everyone can afford to do something about it, and those who can’t are also less likely to have access to healthy food and other preventative measures. Your kids aren’t the only ones who are affected by fluoride in the water.

SUMMARY

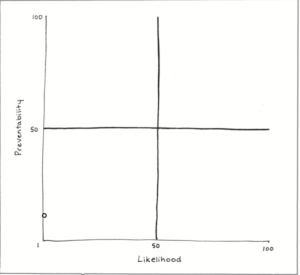

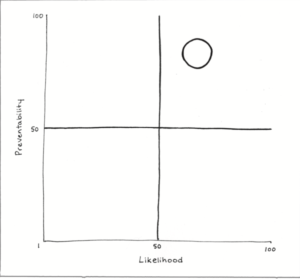

Preventability (5)

You can choose not to use fluoride-containing toothpaste or mouthwash, but if you live in a community with fluoridated water, you’re going to be exposed.

Likelihood (7)

Exposure within the normal range is very unlikely to cause any problems.

Consequence (2)

The most likely effect of excessive fluoride is mild dental fluorosis, which can be unattractive but isn’t dangerous.

*

Aluminum

Aluminum is the most abundant metal in Earth’s crust. It follows oxygen and silicon as the third most abundant element on Earth’s surface. Although oxygen is still almost six times more common than aluminum, there is a lot of aluminum on Earth. Aluminum doesn’t seem to have any biological role, but that’s okay because we use it to do plenty of other things. It’s handy because it is lightweight, easy to shape, and resistant to corrosion. Aluminum is used to make a positively dizzying number of things including pots and pans, cans, foil, w

eatherproof siding and roofing, ductwork, toys, and airplanes.

But it is also used in many ways you might not expect. For example, it is an ingredient in over-the-counter antacids, baking powder, vaccines, buffered aspirins, cosmetics, antiperspirants, and fireworks. Perhaps most surprisingly, aluminum sulfate is widely used in water treatment. To repeat: there’s a lot of it around. According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), “virtually all food, water, air, and soil contain some aluminum.” According to

the same source, adults in the United States eat about 7–9 mg of it every day in their food. Unless you plan to stop breathing, eating, and drinking water, you can’t avoid aluminum. This being the case, if aluminum were toxic, it would be a big deal.

The good news is, contrary to what many people think, aluminum is not especially toxic. Regardless of whether you inhale it, ingest it, or get it on your skin, aluminum is poorly absorbed by the body. And as long as your kidneys are working properly, the aluminum that is absorbed does not tend to accumulate, either in humans or in other animals (like the ones we eat). It doesn’t really accumulate in plants either, with the notable exceptions of tea and some ferns.

Not surprisingly, in large quantities aluminum is not great for you. The nervous system and the lungs are the organ systems that are most sensitive to aluminum toxicity. The neurotoxic effects of aluminum are demonstrated by dialysis dementia, a neurodegenerative syndrome that can occur in people with kidney disease. It results from a combination of a reduced capacity of the kidneys to clear aluminum and an increase in aluminum exposure through dialysis fluid. This leads to an accumulation of aluminum in the brain and symptoms that include the loss of motor, speech, and cognitive functions.

Scientists have also postulated a link between aluminum exposure and Alzheimer’s disease. This connection was proposed decades ago, but

it remains a controversial hypothesis. Some studies have found a correlation between aluminum consumption and Alzheimer’s disease, but others have not. The mixed data make it impossible to make a definitive statement, but scientific interest in the subject seems to have drifted. The Alzheimer’s Association states, “Experts today focus on other areas of research, and few believe that everyday sources of aluminum pose any threat.” We confirmed this with a neurologist specializing in dementia. This isn’t very satisfying, but Alzheimer’s disease is complicated. There probably isn’t just one thing that is responsible.

Aluminum does not appear to cause cancer either. According to an internet rumor that has been circulating for some time, the use of underarm antiperspirant can cause breast cancer. But everyone who has felt guilty for valuing dry armpits over breast health can breathe a sigh of relief. Both the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society say there is no truth to this claim.

An examination of the literature suggests that aluminum is not the metal you should be most concerned about (lead is really at the top of that list). If you still want to limit your exposure to aluminum, unfortunately, it might be difficult to do. A small amount of aluminum is absorbed into food via cooking utensils, especially when you are cooking acidic food. The same is true for antiperspirants: only a small percentage of the aluminum that

makes contact with your skin is actually absorbed. There is very little aluminum in vaccines, and only in some of them (hepatitis A and B, DTaP/Tdap, Hib, HPV, pneumococcus). The aluminum is added because it increases the effectiveness of the vaccine, and skipping a vaccine because of the aluminum is a bad trade-off.

For people who don’t have workplace or industrial waste exposure, the major sources of aluminum exposure are treated water and some processed foods (for example, bread, cereal, and processed cheese). You can certainly cut back on the number of processed foods that you eat; this is in fact a healthy choice for a number of reasons. But it is not a good idea to drink water that has not been treated. If you use antacids frequently or drink a lot of tea, you might also be consuming more than a normal dose of aluminum, and you can reduce your exposure by cutting back on these products.

In some cases, aluminum is the least troubling

part of the equation. For example, if you’re thinking about opening up a can of chicken noodle soup for lunch, you should worry less about the aluminum that may have leached into your food than you should about the BPA it may have picked up from the can lining, or the whopping dose of salt you’re about to consume, or the potential for botulism contamination.

SUMMARY

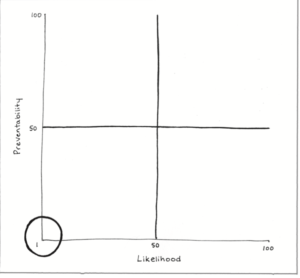

Preventability (10)

Most people are exposed to aluminum primarily through their food and drinking water. So there isn’t much you can do to avoid it.

Likelihood (1)

Unless you are undergoing dialysis or are exposed to much higher doses of aluminum than most people, you are unlikely to su er any adverse outcomes from aluminum exposure.

Consequence (12)

The typical level of aluminum exposure has not been shown to cause any serious health outcomes. The mixed results of studies on aluminum and dementia make the potential consequence score higher than zero.

*

Asteroid Strike

Hurtling toward the city of Chelyabinsk, Russia, at a speed of 19 kilometers per second (68,400 kph or 42,502 mph), the 12,000 metric ton space rock did not make it to the surface of the

Earth. Instead, the asteroid broke into small pieces and, with the energy of 500 kilotons of TNT, burst into a fireball approximately 30 kilometers above the ground. The blast broke windows and damaged buildings. Although some injuries were caused by the shock wave, flying glass, and falling debris, no residents around Chelyabinsk were killed.

This is the scenario that played out on February 15, 2013. About a century earlier (June 30, 1908), an asteroid exploded over the Siberian skies (the Tunguska event), destroying 2,150 square kilometers of forest. Because the area was sparsely populated, there were no casualties. The dinosaurs were not so lucky when a giant asteroid made contact with Earth just off the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico approximately 65 million years ago. This asteroid, estimated to have had a diameter of 10–15 kilometers, created the Chicxulub crater, with a diameter of 180 kilometers. The impact, with a force of 10-100 trillion megatons, resulted in a massive tidal wave and sent up a global dust cloud that resulted in the extinction of many life forms.

Our home planet is showered with tons of dust and sand-sized particles from space every day. Most of these materials burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere and pose no threat. On occasion, an asteroid does make it through the atmosphere. Depending on its size, an asteroid that makes it to the surface can cause minimal local damage or wipe out most life on the planet. The Earth Impact Database lists only 190 confirmed impact craters on Earth dating from 2.4 billion years ago to the present.

For example, about 50,000 years ago, an asteroid weighing 300,000 tons crashed into northern Arizona and created the Barringer crater, 1 kilometer wide and 750 feet deep. The shockwave, heat, and shrapnel created by this impact would have destroyed all life within 1.5 miles.

The destructive effects of an asteroid’s impact on Earth are related to the size of an asteroid. Asteroids with diameters greater than 10 kilometers will result in mass extinctions and likely the total annihilation of all humans. Impacts by smaller asteroids (1–3 kilometers diameter) will likely cause massive death, infrastructure damage, and global climate change. Asteroids with diameters between 100 and 300 meters will cause regional damage and set up devastating tsunamis. Even smaller asteroid impacts can cause many deaths if they strike populated areas.

Asteroid impacts generate several damaging forces including heat, tsunamis, pressure waves, cratering, shrapnel, earth shaking, and wind blasts. Wind blasts and pressure shock waves will likely cause most of the human casualties when asteroids (15–400 meters in diameter) impact the Earth. A 200-meter asteroid striking the city of London would be expected to kill approximately 8.7 million people. With enough warning of an impending asteroid strike, it may be possible to evacuate a city to minimize casualties.

Predicting where and when an object from space will impact Earth is tricky business. The Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (California Institute of Technology) and the Spaceguard Project (Powys, United Kingdom) have created an impact monitoring system to track the orbits of hazardous asteroids. Based on the analysis of an asteroid’s orbit, the Sentry system makes a prediction about the time and location of the asteroid’s impact.

The CNEOS Sentry system currently lists 70 potential Earth impact events within the next 100 years. The asteroid with the highest likelihood of impact (predicted to be between the years 2185 and 2198) has a 99.84% chance of missing the Earth. The other 69 objects have an even greater chance of missing our planet. All 70 objects currently have a 0 on the Torino Impact Hazard Scale. The Torino Scale rates the likelihood and consequences of an asteroid impact. A 0 rating indicates that the likelihood of a collision is essentially zero or that the object is so small that it will burn up in the atmosphere or cause little damage if it hits the ground.

So, currently, no asteroids of any significance have been detected that are on a collision course with Earth within the next 100 years. Nevertheless, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office is still scanning the skies for asteroids and comets that pose a danger to Earth. If a potentially dangerous object is on its way to Earth, given enough time to prepare and deploy a plan, it may be possible to prevent an impact. The key is timing. The sooner an object is detected, the sooner its velocity or direction can be changed, so the Earth can avoid a strike. A system to slow an asteroid by hitting it with another object or by using the gravitational force of another large object placed near the asteroid could work as a defense mechanism.

Exploding a nuclear bomb or ramming a spaceship into an approaching asteroid may not save the Earth from an asteroid’s impact if the asteroid is large or porous. Even if the asteroid did break up, the remaining pieces might still rain down and cause havoc. Detonating a nuclear explosion (or two or three) near an asteroid instead of on it may create enough force to alter the asteroid’s direction. The sooner an asteroid’s course can be altered, the less it has to be moved to avoid a collision with the Earth.

The technology and capability to create and deliver the energy needed to deflect large asteroids are beyond our current capabilities. With decades of planning (and billions of dollars, euros, yen, yuan, and rubles), scientists and engineers might be able to detect approaching asteroids and mount an effort to deflect such objects in order to save life on Earth. In the meantime, it appears that we will not go out as the dinosaurs did, at least not anytime soon.

Feel free to keep an eye on approaching asteroids and comets with NASA’s Asteroid Watch Widget.

SUMMARY

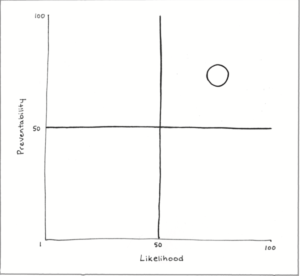

Preventability (1)

No technologies are currently available to stop or alter the trajectory of an asteroid. There is also no action an individual can take that would alter the likelihood or consequences of an asteroid striking the Earth.

Likelihood (1)

The chance of a catastrophic asteroid strike on the Earth within the lifetime of anyone reading this book is extremely low.

Consequence (100)

A large asteroid strike has the potential to wipe out all human life on Earth.

*

Three Things You Should Be Very Worried About

Sugar

To a chemist, sugars are rings of carbon atoms decorated with hydrogens and oxygens, sometimes chained together into strings. In other words, they are carbohydrates. Sugars can be simple or complex, depending on how many rings are strung together. Simple sugars have just one ring and are called monosaccharides. Likewise, if two monosaccharides are strung together you get a disaccharide, and if you add any more than that you just call it a polysaccharide.

Sugars taste sweet, and we like to eat them. This is likely because sugars are extremely important biomolecules. Notably, glucose, a monosaccharide, is the human body’s primary source of energy. It is circulated throughout the body in the bloodstream and is particularly important for the brain, which demands glucose as its exclusive fuel. Sugars serve critical functions elsewhere in the body as well. Most other organisms also rely heavily on sugars.

For example, the disaccharides starch and cellulose are used by plants to store energy and provide structure, respectively. Historically, humans had to either make sugars themselves or ingest them from plants. Sucrose, a disaccharide consisting of a glucose and another monosaccharide, fructose, is found in many plant sources, especially fruits. One plant that is particularly high in sucrose is sugarcane.

Sometime in the distant, murky past of civilization, someone in India figured out how to refine sucrose crystals from sugarcane. This new product (and technology) gradually spread around the world, reaching Europe during the medieval period. Everyone, everywhere, liked sugar, just as we do now. So there was clearly a demand.

But extracting sucrose from sugarcane was difficult and expensive. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until the mid-18th century that anyone realized you could get the same product from a humble beet. And in pursuit of that valuable market share, Europeans began cultivating sugarcane in the New World on huge plantations made possible by slave labor. This made sugar more broadly accessible, and sugar transitioned from an exotic spice to a household staple. It’s not exactly a sweet legacy, to put it mildly.

In modern Western society, refined sugar is a ubiquitous ingredient. It is still derived from sugarcane, but also from beets and corn. It is no longer expensive, and it still tastes great. It is a prime ingredient in all manner of desserts, sauces, condiments, and, of course, sugary drinks. Sugars included in prepared food are called added sugar. We eat a lot of added sugar. Way, way too much.

There is some debate about how bad for us sugar really is, but everyone agrees it’s bad. Sugar consumption is linked to tooth decay, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease. These conditions lead to risk factors for other diseases, like cancer and blindness.

So how did something that is vital to life turn into something that is making us flabby and slowly killing us? Sucrose is naturally found in fruit, and fruit almost always gets a nutritional thumbs up. The problem arises when you remove the sugar from the fruit and consume it in a different context. In addition to sugars, fruit is full of fiber and other vitamins and beneficial compounds. This is important in at least two ways. First, fiber slows down absorption of sugar. Second, it limits the amount of sugar you can eat in one sitting without getting full or experiencing gastrointestinal distress.

In contrast, a can of soda has no fiber, no protein, no vitamins, and can contain up to 12 teaspoons of sugar, which causes a huge spike in blood sugar. Sugary drinks are especially problematic because, in addition to having high caloric loads, the body doesn’t register those calories in the same way as it does with food. The same number of calories is not equally satiating, and therefore it is very easy to consume a lot of calories without even realizing it. Humans evolved in an environment where calories were scarce, and therefore our bodies store them rather than eliminate them when we over-consume.

One of the more common added sugars, high-fructose corn syrup, may be extra bad for us. This is because, as the name implies, this sugar has a slightly higher ratio of fructose to glucose than table sugar. Unlike glucose, fructose has to be metabolized by the liver before it can be used by the body. Some of the by-products of fructose metabolism are undesirable, like triglycerides—fats that are associated with heart disease. This is somewhat controversial, but regardless, most of us need to cut back on the refined sugar that we eat (and drink). This includes natural sweeteners like evaporated cane juice, honey, agave nectar, and maple syrup.

As it happens, sugars are not the only compounds that taste sweet. Some sweet-tasting compounds like ethylene glycol and lead acetate are incredibly poisonous, but others are innocuous. This latter category is appealing to people looking to reduce their sugar intake. Aspartame, saccharin, stevia, and sucralose are examples of nonnutritive sweeteners. They are sweet, much sweeter than sugar, but they usually don’t taste quite the same. Nevertheless, they can make a passable substitute and have become very popular among the calorie conscious.

Unfortunately, they don’t appear to have any positive impacts in terms of body mass index or cardiovascular health. On the contrary, they are sometimes associated with increased weight gain, high blood pressure, diabetes, and cardiovascular problems. That sort of defeats the point, so at present there does not appear to be a good alternative to curbing the sweet tooth, except in the case of tooth decay. Sugar-free gum is unambiguously better for your teeth than sugar gum, as it even helps to prevent cavities.

The easiest way to reduce your added sugar consumption is to stop drinking sweet beverages such as sodas, blended coffee, energy drinks, powdered drink mixes, and even fruit juice. The next categories to tackle are candy, desserts, and processed foods. For healthy people, whole fruits are a healthy food. However, not all fruits are created equal, and some will have more sugar than others.

Sugar isn’t really bad for you, per se. It’s the quantity that’s important. It’s okay to indulge in sugar as an occasional treat—as long as you don’t define occasional as several times every day.

SUMMARY

Preventability (77)

Sugar is in most processed foods. You can cut back, but it is hard to cut it out completely.

Likelihood (75)

Eating too much sugar is very likely to damage your health.

Consequence (65)

Obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and tooth decay are all quite common. They can also be quite serious.

*

Lead

If you don’t already know that lead is toxic, you haven’t been paying attention. Lead is notoriously poisonous. Lead poisoning can be acute or chronic, both of which are very serious. Lead has detrimental effects on all of the organ systems in your body, but it hits the nervous system especially hard. This is because lead mimics calcium, an important player in the brain. Lead easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, where it builds up in nervous tissue; it also accumulates in bone, another organ system heavily dependent on calcium. It is toxic both when it is ingested and when it is inhaled as lead vapor or dust. Children are more vulnerable to lead because they are smaller, and their brains are still developing.

Since at least the late 1800s, it has been known that lead is poisonous. But toxicity aside, lead has some very desirable properties. It is a dense, malleable, abundant, easily mined metal that is resistant to decay, is impenetrable to radioactive particles, and has a low melting point. And it tastes sweet. The Romans used it to sweeten wine—an exceptionally bad idea in retrospect.

The overwhelming harm caused by lead has resulted in heavy regulations in the United States since 1980. And these regulations have significantly reduced the public’s exposure to lead. Average blood lead levels decreased by a factor of 10 between children studied in 1976–1980 and 2007–2008. This is great.

Unfortunately, there is still a lot of lead out there. Some of it is legal (e.g., in car batteries, solder, hair dye, dental aprons), and some of it is illegal (e.g., in children’s toys, ceramic glazes), and a lot of it is legacy (e.g., in paint, pipes, dirt, crystal, jewelry). The list of things that historically contained lead is so long that it is difficult to compile and impractical to print. Lead is in seemingly everything (except pencils, which are filled with graphite).

The question then is not whether lead is bad for you, but how bad it really is. Most people who were born before regulations were passed in 1980, and those born in the next decade after, were exposed to lead as children. Leaded gasoline was sold until the late 1990s, and many people lived in houses that were built before lead paint was banned in 1978. Lead water pipes and fixtures were commonly installed in homes and schools before 1986, and many students learned to solder in high school with lead-based solder.

And we’re fine, right? That’s difficult to say, because many of us may be suffering the adverse effects of lead exposure without attributing them to lead. Lead is associated with loss of IQ points, behavioral problems, tremor, cognitive decline, hearing problems, allergies, cardiovascular problems, kidney disease, and reproductive issues. Concerningly, a 2012 report by the National Toxicology Program (“NTP monograph on health effects of low-level lead”) found evidence for some of these health effects even at low blood concentrations (less than 10 micrograms per deciliter and in some cases less than 5 micrograms per deciliter). The CDC has revised the high blood lead level down from 25 micrograms per deciliter in 1985 to 10 in 1991 to 5 (the current level) in 2012. They emphasize that “no safe blood level in children has been identified,” but it is important to remember that the health effects of lead are not limited to children.

If a blood test reveals high lead concentrations, chelating agents can be used to reduce the burden of lead. However, after the body is damaged by lead, especially if this damage affects the nervous system, it is irreversible. So it’s worth trying to prevent lead exposure in the first place.

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the most common sources of lead in the U.S. are lead-based paint, contaminated soil, household dust, drinking water, lead crystal, and lead-glazed pottery. Of these potential sources, it is easiest to avoid lead crystal and lead-glazed pottery. Don’t eat off it and don’t drink out of it.

Drinking water is trickier, because as individuals we don’t have the authority or resources to rip up and replace the city pipes (think Flint, Michigan). Most of us don’t even have the resources to rip out the lead pipes from our own homes. You can buy water filters that will remove lead and other heavy metals, but you need to make sure that the filter you are using is certified for that use.

Lead contamination in dirt is usually the result of either decaying lead paint or historical exposure to leaded gasoline fumes. Dirt around older homes or close to high-traffic areas is most likely to be contaminated. Exposure to lead in soil can be either direct (like children putting dirty fingers in their mouths) or through produce grown in the soil. Soil that is potentially contaminated can, and should, be tested.

The biggest problem in terms of lead exposure is paint. Old lead paint cracks, chips, and flakes. This poses a risk to children, who may eat paint chips (remember, it’s sweet), but it also produces a fine dust that can be ingested or inhaled by children, adults, and pets. This is a huge problem because there are so many residences painted with old lead paint. You should just assume that any older paint you find in your home has lead in it, but you can also buy lead paint test kits at the hardware store. The problem is, what do you do if you have a positive test? The best (but most expensive) option is to call in a lead abatement professional. If you are considering renting or buying a home or planning a remodel, have it tested for lead first.

Lead tends to accumulate in household dust because of decaying paint, contaminated soil, or both. So try to keep the dust levels in your home down (this is a good idea anyway). Make sure everyone in your family washes their hands frequently, and teach your children not to put nonfood items in their mouths (easier said than done). Also, buy high-quality children’s toys and pay attention to the Consumer Product Safety Commission recall list. Be aware that your home isn’t the only place you can be exposed to lead. You also need to think about workplaces, schools, day care centers, and playgrounds. Finally, if you’re worried about lead exposure, get a blood test.

If you grew up with lead paint, your IQ may have taken a permanent hit from lead. But if you take precautions, you may end up with kids that are smarter than you are. That might be its own kind of problem.

SUMMARY

Preventability (74)

There is a lot of legacy lead in buildings, water pipes, and even dirt. But if you take precautions, you can reduce your lead exposure.

Likelihood (80)

Even very small quantities of lead can have measurable negative outcomes.

Consequence (79)

Lead can have negative consequences for all of your organ systems, but it is especially bad for your brain.

*

Alcohol

Colloquially, when people talk about alcohol they are referring to ethanol, which is what is found in alcoholic beverages. Chemically speaking, ethanol is only one member of a large family of compounds known as alcohols. You are probably familiar with some of the other family members, such as isopropyl alcohol, also known as rubbing alcohol, or ethylene glycol, which is commonly used in antifreeze. But as useful as these other compounds are, ethanol’s combination of disinfectant, psychoactive, and nontoxic properties have made it humanity’s longtime favorite. It is the only kind of alcohol that you should consider imbibing, and you should consider it carefully.

Ethanol is the by-product of the fermentation of sugar by yeast. Humans have been taking advantage of this process to make alcoholic beverages since time immemorial. Alcohol has been used medicinally, ritually, and recreationally for thousands of years. It continues to play a social role in many cultures worldwide and is a huge global industry. But for as much as we like it, humanity’s relationship with alcohol has been fraught with struggle, and alcohol consumption has a very dark side.

As a drug, alcohol has system-wide effects on the body. Notably, it reduces inhibition and increases sociability, impacts judgment, impairs motor function, increases reaction time, acts as a diuretic, and dilates blood vessels. In high doses it can cause vomiting, dizziness, unconsciousness, amnesia, respiratory depression, and decreased heart rate. Acute alcohol poisoning can be fatal. It is, in fact, fatal for about six Americans every day. Of course, alcohol is also addictive and is the most commonly abused substance in the United States.

Heavy alcohol use taxes the liver, and cirrhosis is a common and well-known side effect. Wernicke-Korsako syndrome is a less well-known but equally serious condition that is secondary to chronic alcoholism. This disorder, which is a type of dementia, is the result of thiamin deficiency. Alcohol interferes with the body’s ability to absorb B vitamins, such as thiamin and folate. Malabsorption of folate may partially account for another of alcohol’s adverse side effects—increased cancer risk. Alcohol consumption increases the risk of a number of cancers including breast, colon, rectum, liver, mouth, esophagus, and larynx.

In addition to these direct physiological effects, alcohol is associated with a range of negative social outcomes. Domestic violence, child abuse, sexual assault, and accidents, especially motor vehicle accidents, are all made more likely by alcohol. Pretty much any way you look at it, the world would be a safer place without alcohol.

Even so, as a species, humans are very unlikely to give up alcohol. And at this point, you might be mentally protesting that some positive health outcomes are associated with moderate alcohol use. Everyone has heard somewhere that drinking a glass of red wine is good for the heart. It’s true that alcohol may have protective benefits against stroke, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Some studies have shown that moderate drinkers have a reduced mortality risk compared to both heavy drinkers and abstainers.

Unfortunately, reanalysis of some of these studies has shown that when other factors are accounted for, moderate drinkers really don’t have any mortality advantage. Furthermore, the risks associated with alcohol consumption are so great that they outweigh any potential cardiovascular benefits. This being the case, no one is recommending that anyone start drinking alcohol for health reasons. If you have safe drinking water available, there really aren’t a lot of medically sound reasons to drink alcoholic beverages. The only reason to drink alcohol is because you enjoy it. But drinking isn’t really going to be fun if it kills you, so you should drink in moderation.

You might think you’re a moderate drinker, but are you? The recommendation for moderate alcohol consumption is one standard drink a day for a woman and two drinks a day for a man younger than 65. If you’re a man older than 65, you also only get one drink a day. This doesn’t seem fair, but physiology isn’t fair. Women and men metabolize alcohol differently because of different body composition; this is the same for older people as compared to younger people. And back to that idea of a standard drink. One drink is 12 ounces of 5% alcohol by volume (ABV) beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of liquor. If you drink a pint of craft beer with 7% ABV, you are having more than one drink. If you are a woman and drink four or more drinks in two hours, or if you are a man and drink five or more drinks in the same amount of time, you are binge drinking.

Of course, there are some times in life when you should abstain completely. There are some medications, painkillers and allergy pills for example, that do not mix well with alcohol. If you’re taking any medications—prescription, over-the-counter drugs, or herbal—ask your doctor before you imbibe. Another time to teetotal is during pregnancy. This has been standard medical advice for many years, but recently women have been feeling a bit more relaxed about having one glass of wine. It is understandable to want to relax with a buttery chardonnay, but it’s probably not a great idea.

The official medical line is, “there is no known safe amount of alcohol during pregnancy.” That doesn’t mean there isn’t a safe amount, but we don’t know what it is, and it would be unethical to run a clinical trial to find out. That is because it is well known that alcohol can have profound, life-long consequences for an unborn child, including fetal alcohol syndrome. In addition, pregnancy isn’t a static condition but a complicated process. There may be some times during gestation that alcohol will be more likely to do damage to the fetus than at other times. It probably isn’t worth the risk. Reference the above comment about the general unfairness of physiology. Once that baby is born, they should also refrain from drinking alcohol until adulthood. Teenagers may have already achieved their adult height, but they have not yet achieved their adult brains. Drinking during this period of life can have permanent negative impacts on cognitive function.

If you enjoy wine tasting or martinis or craft beers, all of the above can seem like a downer. Life can be that way. In the end, you have to define your own priorities for your life and balance health concerns with life’s pleasure. Cheers.

SUMMARY

Preventability (85)

Unless you already have an alcohol dependency, you can choose whether you want to imbibe and how much. So the preventability score is high. On the other hand, you can’t control whether other people drink, and other people’s drinking habits can have profound effects on your life, so preventability isn’t perfect.

Likelihood (65)

Many people enjoy the occasional drink without a problem, but the incidence of alcohol-related trouble is quite high.

Consequence (90)

The consequences of excessive alcohol consumption range from a bad headache, to liver damage, to domestic violence, to death. The potential negative outcomes are so many and so severe that the consequence score is high.

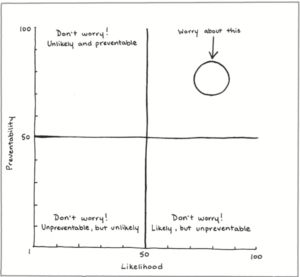

*How to Interpret the Worry Index

You will notice that for every topic reviewed on this list we have assigned a three-dimensional worry index. The three components of the index are preventability, likelihood, and consequence, defined as follows.

Preventability: The preventability score refers to your ability to avoid or mitigate a specific outcome. If there is something you can do, then you have some control. The more you can do to prepare, the higher the preventability score.

Likelihood: The likelihood score refers to the chance of a negative outcome should you be exposed to a particular element of risk. The greater the odds of an adverse result, the higher the likelihood score.

Consequence: The consequence score refers to the potential magnitude of harm. The more dire the consequence, the higher the consequence score.

In all cases we have assumed that the issue is relevant to you. We have also assumed a typical level of exposure. Obviously, these assumptions aren’t appropriate for everyone all the time.

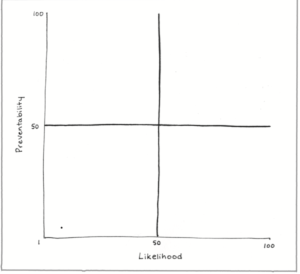

For each topic, we have provided a plot that represents these three factors graphically. The vertical axis (the y-axis) represents preventability; the horizontal axis (the x-axis) represents likelihood; and the size of the marker represents the consequence. Each plot is broken into quadrants. If you follow our suggestions, you will focus most of your effort addressing the large points in the upper-right quadrant. These are the problems that are preventable, likely to happen, and potentially serious. These are the things you should worry about.

If you’re wondering how we came up with this scoring method, the answer is: we made it up. If you’re wondering how we assigned the values, the answer is: we discussed and debated the scores for each topic until we agreed. You are free to disagree with us.

In most cases, it was difficult to assign a real number to the preventability, likelihood, and consequence of a particular risk factor. Almost all the time the answer seemed to be “it depends.” You may find, as we did, that this is very unsatisfying. Therefore, we have done our best to make an estimate. We like to think of these estimates as a good first pass. But we strongly caution you against reading too much into the score.

__________________________________

From Worried? Science Investigates Some of Life’s Common Concerns Used with permission of W. W. Norton & Co. Copyright © 2019 by Lise Johnson and Eric Chudler.