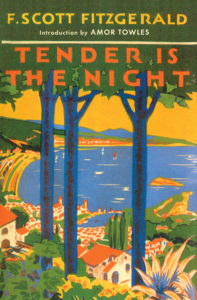

Scenes From a Marriage:

Reading About My Great-Grandparents, Scott and Zelda

Blake Hazard Introduces Tender Is the Night

I first read Tender Is the Night as a girl of roughly the same age as Rosemary Hoyt, the young actress in the novel—in that same bloom of youth with which Dick Diver is so enthralled. I was on my way to a Fitzgerald conference in the South of France, where the novel takes place, and where my grandmother lived briefly as a child with her expatriate parents, Scott and Zelda. I had never been encouraged to read my dazzling but troubled great-grandparents’ work; a sort of taboo had formed in our family around them, and their books seemed to belong more to the world than to me. But before we left for France, my mother suggested I read this novel about their days on the Riviera, and I eagerly obliged.

Infused with the same romantic arrogance of youth that Scott describes so beautifully in the book, I felt I understood Rosemary’s precarious position between innocence and experience. The language of the novel itself, at times reading like finely tuned poetry, and at times colorfully fragmented and impressionistic, was so strikingly modern that it felt timeless; the themes of romance, success, madness, and loss felt fresh, and the dark tangle of the love story felt true.

I also understood that the characters Dick and Nicole Diver were meant to be a kind of composite of Scott and Zelda, along with their close friends Gerald and Sara Murphy, to whom the book is dedicated. The novel takes place at a time resembling the moment in Scott and Zelda’s own lives when they had reached a certain crescendo, when Zelda’s mental health had unraveled and Scott’s problems with alcohol were undeniable.

Aspects of Nicole’s character, and the way she speaks, have fused with my idea of Zelda herself. Her peculiar turns of phrase capture an unsettling strangeness, and likely come from Scott’s close observations of Zelda. This borrowing of material from their life together was a source of bitter dispute between the two. Before Scott could finish Tender Is the Night, Zelda published a novel, Save Me the Waltz, drawing from similar chapters of their experience. Furious at having the inspiration for his next novel usurped, Scott employed a stenographer to record one of their couple’s therapy sessions, insisting that he deserved to be in possession of this shared history, that he should have had the chance to publish it in his own words. He had put his career as a novelist on hold while he wrote the short stories that funded Zelda’s care in hospitals and clinics. Though Scott was incensed, I think their novels stand apart beautifully as two sides of a story, however fictionalized they may be.

The atmosphere of Tender Is the Night colored our time in France. A few days into our trip, in the medieval town of Saint Paul de Vence, my mother pointed out a set of stairs down which Zelda had thrown herself in a fit of jealousy. I was filled with a frightened sense of awe to think of her acting so recklessly. (I also learned that the object of Zelda’s jealousy that night, Isadora Duncan, was eventually strangled by her own scarf, caught in the tires of a convertible on a street close to our hotel.) This heady swirl of literature and history gave a new animation to these characters, both in the novel and in my family. In the novel, Nicole Diver shares some of Zelda’s impulses; she’s driven to a breaking point when she suspects Dick of flirting. Dick strives to save her—much as Scott often attempted to rescue Zelda, both men struggling to fend off a dissipation of their own.

The novel came to mind again a few years later, when I worked as an au pair for an American family summering near Saint-Tropez. One afternoon I watched from the backseat of a convertible as the children’s mother sipped a glass of wine, speeding down the same cliff roads where Nicole—and Zelda, in real life—caused their spouses to swerve out of control. The dangers of excess, and the illusive protection of wealth in Tender Is the Night, seemed to haunt every turn.

More recently, as my own first marriage came to an end, I recalled a small but significant moment in the novel. When Nicole and Dick agree to the terms of their divorce, Scott writes that Nicole “felt happy and excited, and the odd little wish that she could tell Dick all about it.” That impulse to share news with the one who was until recently the closest person in the world continues in spite of the split, and I love this subtle telling of that sentimental tic. How amazing, in that moment when one is raw from a breakup and suddenly on one’s own, to read, “You are no longer insulated; but I suppose you must touch life in order to spring from it.”

Each page of the novel offers brilliant insight into human experience—the way people see each other up close, and at a greater social distance. I sincerely appreciate having this emotional thread to my great-grandfather, and am pleased that we are all able to share that connection through his work, as readers. Having read and identified with Scott’s writing, I now work to help safeguard his legacy as a trustee of his literary estate, and I no longer feel the distance from Scott and Zelda that I did when I was young. The novels, short stories, and letters they left behind grant us entry into the hearts and minds of two beautiful, “romantic egoists.”

I’d like to note in closing that unlike Scott’s phenomenal power of description and his extraordinary gift with dialogue— all of which have aged extremely well—his views on race have not. It might be easy to excuse the racism in this work as simply being a product of its time. But, having had the wherewithal to eschew other contemporary norms, I feel Scott might have been able to shed some of the views that he reflects here. I find his not having done so regrettable. As it is an undeniable element in the work, it remains here in the text.

__________________________________

From the foreword to Tender Is the Night. Used with permission of Scribner. Foreword copyright © 2019 by Blake Hazard.

Blake Hazard

Blake Hazard is a singer songwriter living in Los Angeles. Blake was born in Vermont and attended Sarah Lawrence College and Harvard. She and her band, The Submarines, have toured internationally behind their three albums, and have also licensed their songs for film and television. Most recently, Blake released two studio albums independently as a solo artist. She serves as a trustee of the Fitzgerald Estate.