In 1945, Samuel Beckett published an article entitled “Le Monde et le pantalon” (“The World and the Trousers”), which discussed the Dutch painters Abraham and Gerardus Van Velde, familiarly known as Bram and Geer.

Beckett concluded that “We are only just beginning to talk rot about the Van Velde brothers. I open the series. It is an honor.”

It is true that Beckett was talking rot. Indeed he was the only writer or critic, apropos of Bram in particular, who performed brilliantly in this respect. He said for instance that one picture “makes a very distinctive noise, that of a door slamming far away…”

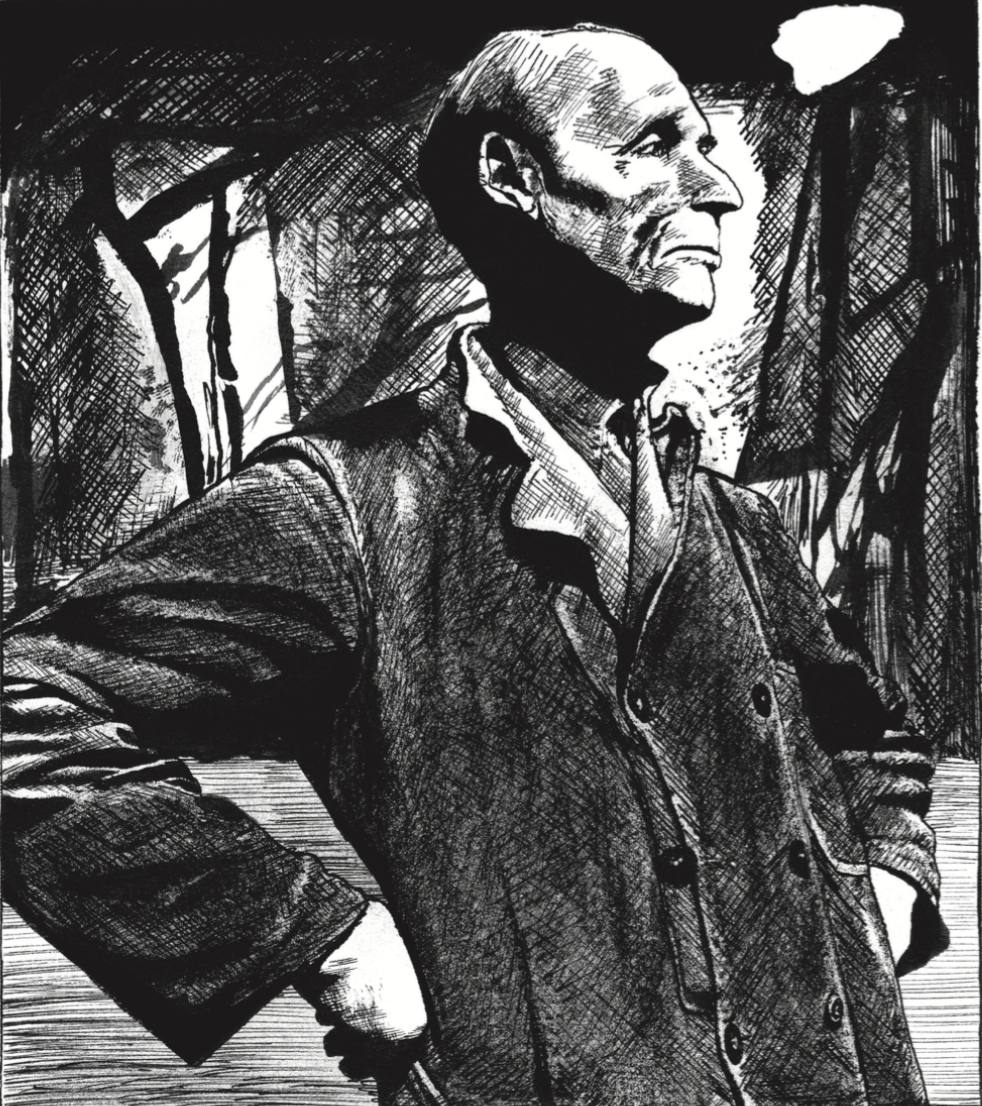

Several times—even reluctantly—he returned to the case of Bram Van Velde. But Bram, true to himself, resisted all rot, sighing: “I don’t like talking. I don’t like people talking to me. Painting is silence.”

Van Velde was a serious guy. He was guileless, sometimes found himself grotesque, and knew that he could be the butt of mirth. After reading Endgame, he acknowledged that he had found some of his own observations in it. Beckett considered him the very model of “the totally desperate man.”

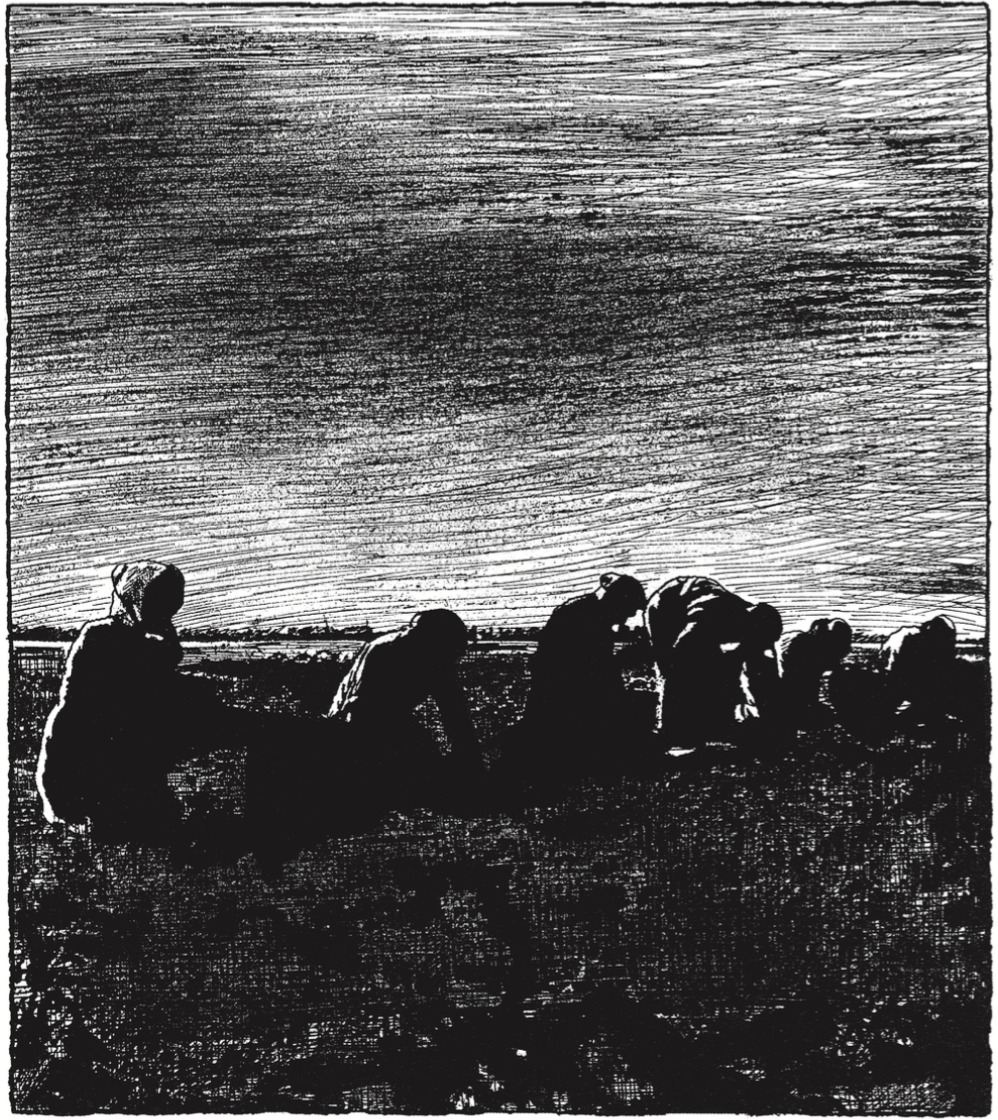

Van Velde dwelt in the sacred, in suffering, in indigence, just like his compatriots Van Gogh and Mondrian, steadfastly opposed to laughter, utterly hostile to excessive derision, and burdened down by the immense angst of Protestant lands.

Nor should we forget Beckett’s Protestant upbringing and its role in his writing, his personality, his rather disdainful prudishness and his taste for the unsaid.

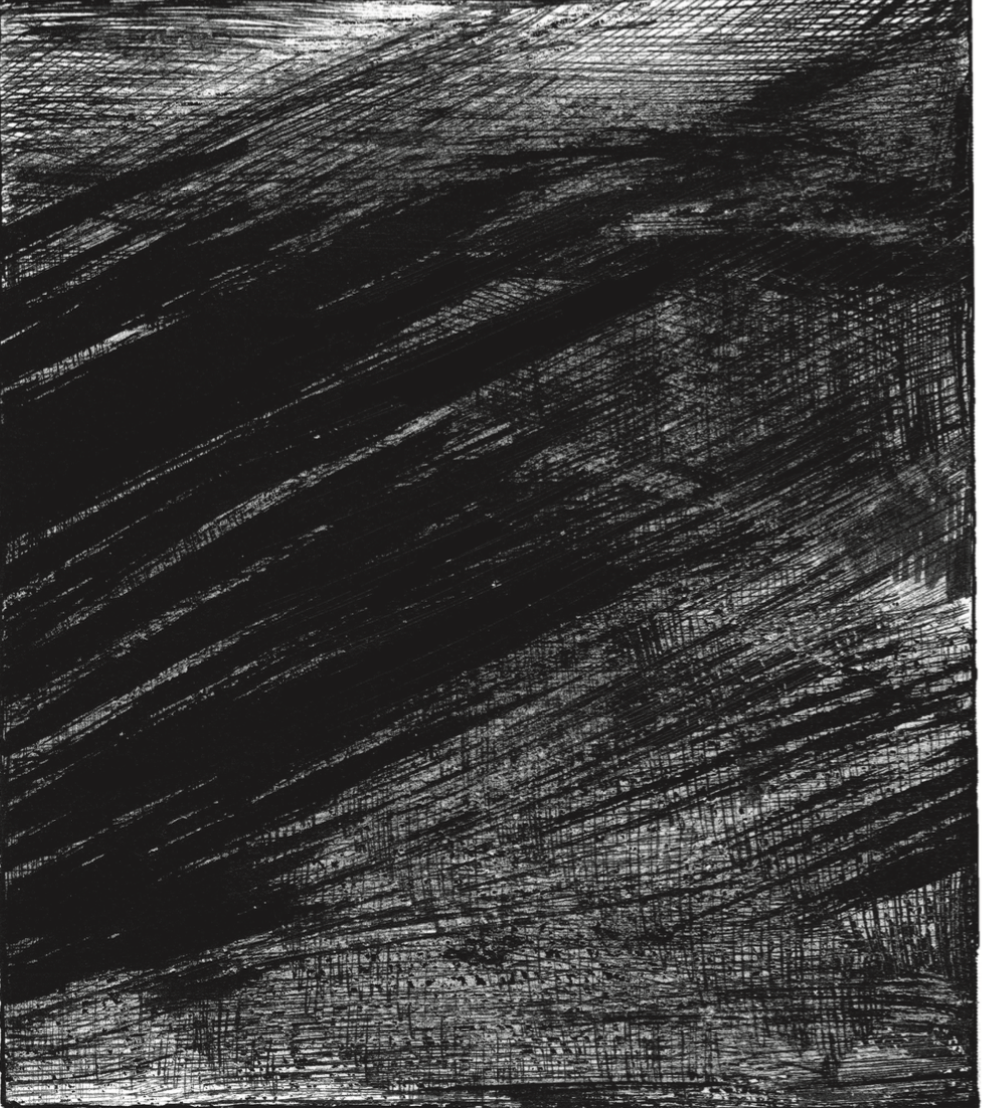

Indeed, did he not see Van Velde as the perfect exponent, in all his austerity, of the unsaid? Better put, he finally found in Van Velde the painter unable to paint because there was “nothing to paint.”

“Are you saying,” asked a Georges Duthuit practically invented by Beckett, “that Van Velde’s painting is inexpressive?”

To which Beckett’s reply, two weeks later, was “Yes.”

Protestant, then, but also a joker, Beckett could find Van Velde’s abstemiousness amusing. He did not mock it, however, nor complain about it: rather, he enjoyed it, admiring and enthusiastic. Did this exiled artist perhaps remind him of his own exile? After all, exiles are a race.

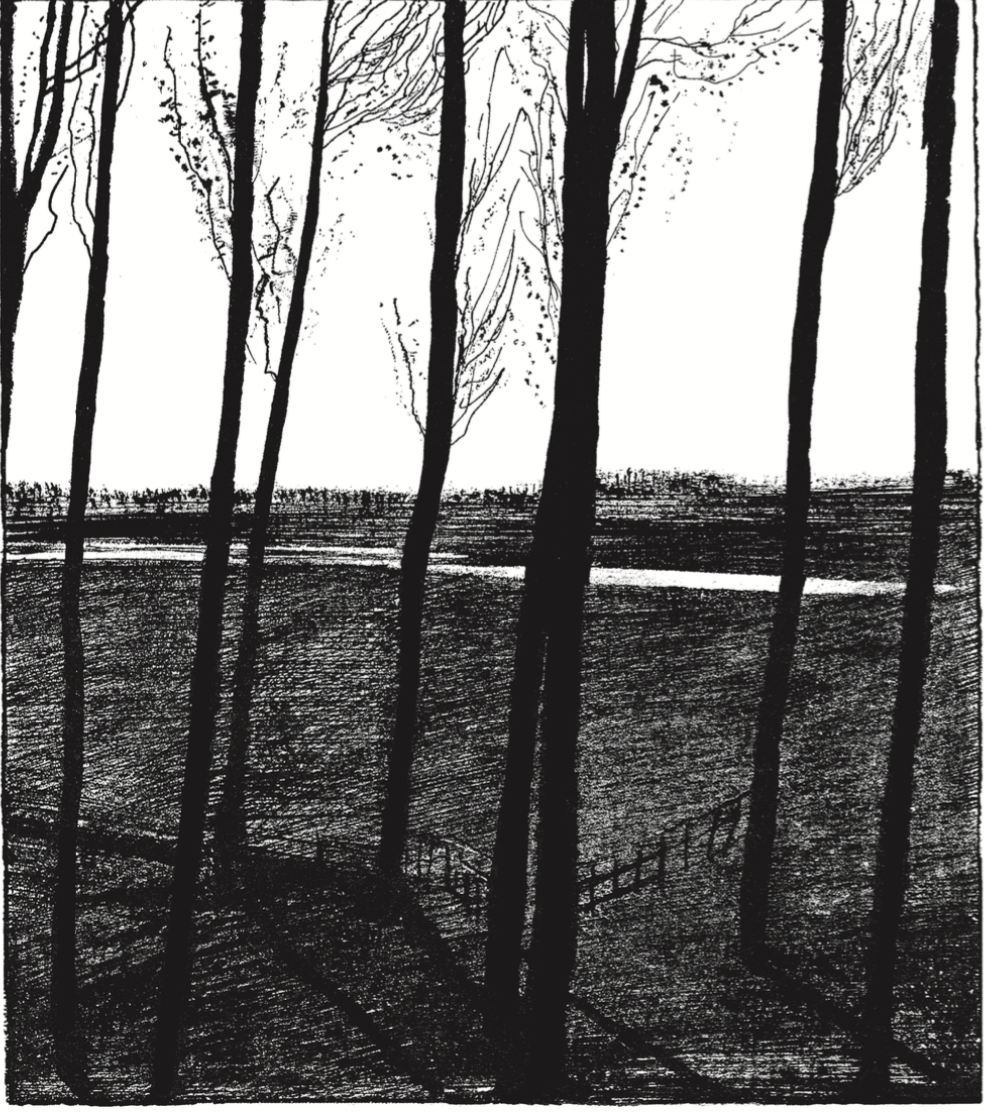

Van Gogh carried his inconsolable sadness with him from his country, horizontal as far as the eye could see, to a eld of wheat, just as horizontal, where he put a bullet in his chest. As for Mondrian, he landed in Paris, then in New York, with, firmly preserved in his mind’s eye, rectilinear fields of tulips or potatoes stretching far into the distance.

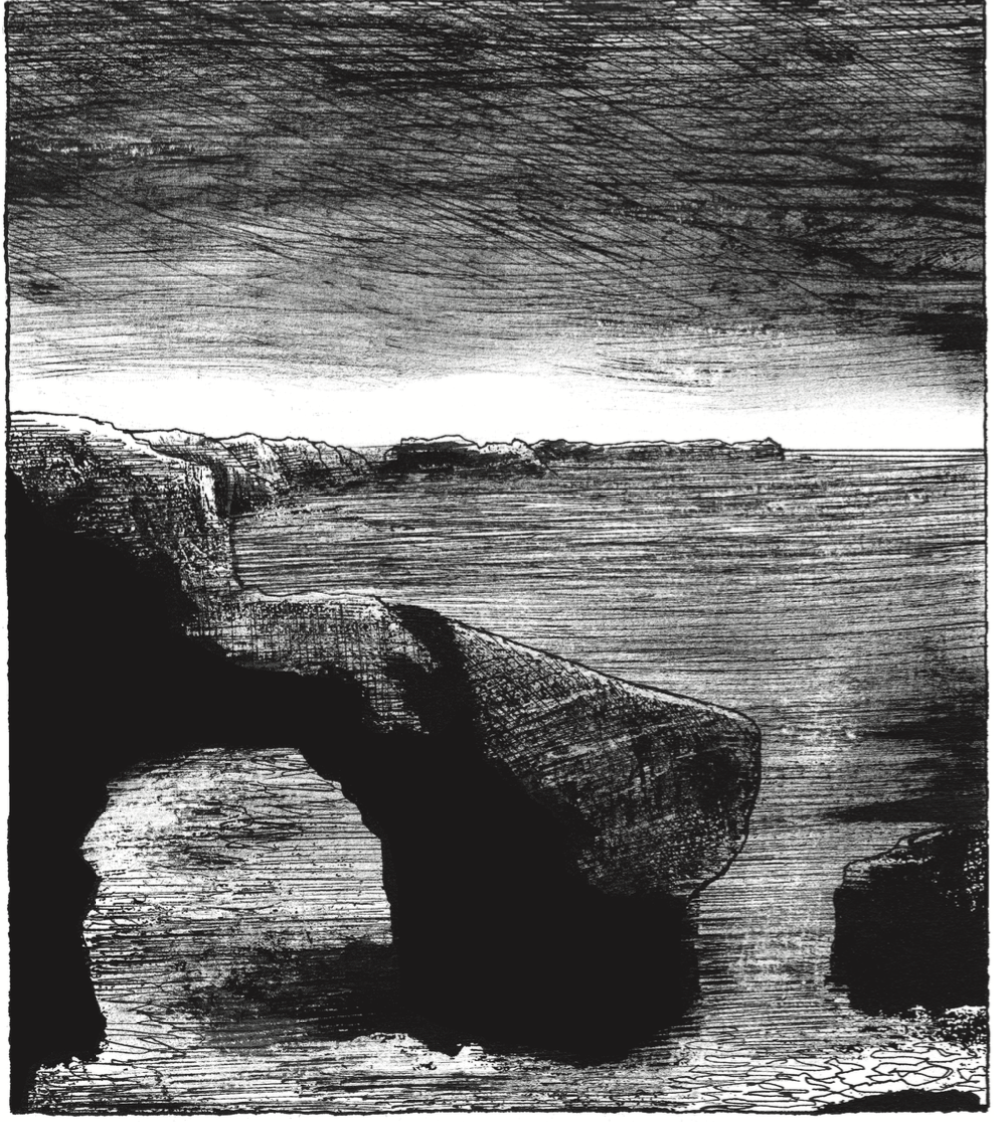

Van Gogh and Mondrian’s paintings are streaked with horizon—the horizon of their native land. Van Velde’s paintings tend to the vertical. Considering that he quit the same gray, at country as they, what was it that he took with him that enabled him to have his pictures resemble open windows? Was it perhaps a few trees standing here or there, or the sails of a windmill, sole suggestions of verticality beneath the void of his sky, which he trailed along with him everywhere, even as far as Corsica and Majorca?

No exile forgets his country. When he met his young compatriot Samuel Beckett, the perpetual exile James Joyce reminded him of the rule: “Ulysse a fait un beau voyage, no doubt about it, but then he went home.”

Beckett never fully left his island, or his language. For a time he was nourished by the words of that incorrigible and impenitent Jesuit of a master, but then he found his own voice, his own laugh and, above all, the wherewithal to prompt laughter. He became the comic Protestant, a precursor able to transform any abby conversation into a dialogue simultaneously funny and devoid of hope, at once realistic and improbable.

In Van Velde’s gaze Beckett believed he spied a brother, the first to acknowledge that “to be an artist is to fail as no other dare fail.”

What an extraordinary misunderstanding! Whereas the one jubilantly turned his world into a clown show, the other opened his window onto silence and nothingness and there unsmilingly limned a few broad black lines between splashes of color—and this without forgetting to repeat that “Each painting contains so much suffering.”

By comparison with the painter, Beckett resembles a thoroughbred at the gallop, clearing hedges in a ash, and suddenly pulling up at the sight of this workhorse, long-suffering and mute save for a few definitive whispered words, such as: “Painting doesn’t interest me. What I paint is beyond painting.” Or again: “I paint the impossibility of painting.”

Prompted by this, Beckett’s response is: “What indeed is this colored surface that wasn’t there before? I don’t know, having never having seen anything like it before. It seems to have no relationship to art—not, at any rate, if my memories of art are correct.”

And so forth.

Beckett talks rot, granted. But not always. He is the one who declares that he is not an intellectual, that he is mere sensibility, and is moved by this painting, by “everything it offers by way of the irrational, the ingenuous, the incoherent, and the mal-léché.” Here he is getting close to its mystery, and relishing the fact, but he quickly reverts to his rot. He knows only too well where Van Velde’s angst can lead. And he knows in advance that in this staring match Bram will surely be the victor.

–Translated from the French by Donald Nicholson-Smith

__________________________________

From Uncertain Manifesto. Used with permission of New York Review Books. Copyright © 2019 by Frederic Pajak.