Roxane Gay on the History of Women and the Oscars

“Clearly, some years, cinematic offerings are more

encouraging than others.”

I love movies—the good, the bad, and everything in between. I can get down with the stylized action of the John Wick franchise as much as I enjoy a taut and intense drama like Room, for which Brie Larson won the Best Actress Oscar. I’ll laugh at the implausibility of romantic comedies and sit, holding my breath, as I watch Natalie Portman take on the role of a prima ballerina in Black Swan.

As a feminist cultural critic, I am particularly interested in women’s stories, whatever those stories may be. Each year, I see as many movies as I can—to be entertained, for sure, but also to understand how movies reflect what we value as a culture, and what we imagine to be possible for women. People are often surprised to learn that one of my favorite movies is Pretty Woman (1990), for which Julia Roberts was nominated for Best Actress, playing Vivian, a prostitute who shows a brooding billionaire how to love and be loved. Roberts was incredibly charming—sexy but just innocent enough to be appealing instead of intimidating. She was smart but human. She was bad but good. Despite her charismatic performance, Roberts did not win that year. Kathy Bates did, for her turn in Misery as Annie Wilkes, a lonely, obsessed fan, who held her favorite writer captive in icy Colorado until he re-wrote one of his stories to her satisfaction. Bates’s win was particularly gratifying because she did not fit the typical mold of women who win acting Oscars.

Clearly, some years, cinematic offerings are more encouraging than others. Some years, the film industry offers us the distinct impression that we cannot imagine anything for women that doesn’t revolve around derivative stereotypes and the expectation that women are merely decorative and involved in any given story only insofar as she will help a man learn something significant about himself or achieve some grand ambition. But then, there are the years when women get to be fully inhabited, fascinating characters. Take, for example The Piano, where Holly Hunter plays a mute woman and evokes so much with her remarkable performance, much of which is rendered in silence.

The best actresses should be lauded for their work, certainly, but this is also a valuable opportunity to consider who has been left out of the conversation.

There are exceptions yes, but they are exactly that—exceptions. The film industry has, historically, offered women so little in the way of depth, nuance or intelligence that the Bechdel Test exists. For a movie to pass the Bechdel Test, it needs to feature at least two women, who talk to one another, about something other than a man. This test is so desperately simple. The bar is so very low and yet here we are. Alison Bechdel gave rise to this test in 1985 and to this day not nearly enough movies actually pass her test.

Throughout cinematic history certain, persistent and limiting tropes have dominated women’s roles. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl is a woman who is quirky and offbeat and helps a disaffected young man find happiness and fulfillment. The Mary Sue is a woman who is seemingly perfect—beautiful, intelligent, always saying and doing the right thing at the exact right time. When a woman is an Ice Queen, she is cold and ambitious until, of course, the right man melts her heart. The Psycho is the woman who wants and needs too much and dares to let those wants and needs be known. Women of color deal with even more restrictive tropes, when they are given a rare opportunity for representation. There is the sassy black friend or the sassy Latina friend or the Magical Negro, full of wisdom for everyone but themselves. They do not have inner lives. They neither want nor need for anything but to serve the white characters around them.

This, however, is not always the case. Though the roles available to women in film are often quite lacking, though these roles often treat women as caricatures rather than characters, the best actresses make the most of the material they are given. That is what makes their performances so extraordinary—how these actresses soar past the limitations of their work. These actresses transcend narrow tropes and infuse their roles with heart and courage, grace and intelligence. In The Accused, Jodie Foster plays a woman who has been brutalized by a gang of men but is determined, with the help of a committed lawyer, to finding justice for herself. Charlize Theron brings unexpected nuance and grit to her portrayal of serial killer Aileen Wuornos and manages to inspire empathy rather than disgust. In La Vie en Rose, Marion Cotillard embodies the spirit of Édith Piaf bringing an icon vibrantly to life once more.

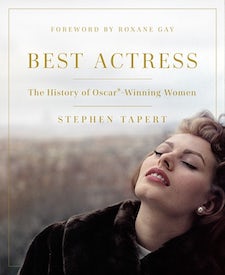

Best Actress: The History of Oscar-Winning Women focuses on the first 75 women who won the Oscar for Best Actress between 1929 and 2018. It is a testament of just how talented the best actresses are despite the constraints of misogyny. These women are remarkable but in looking at the list, what is striking is who has won this award year after year. From Janet Gaynor in 1929 up until today, only one black woman, Halle Berry, has ever received this recognition. She did so in 2002 for Monster’s Ball. No other woman of color has ever received this award. No out lesbian has ever won the award. The women who have won this award are generally conventionally attractive, thin, and gender conforming. They represent what we, as a culture value in women. The best actresses should be lauded for their work, certainly, but this is also a valuable opportunity to consider who has been left out of the conversation, to consider the best of the women who have been overlooked on and off the screen.

————————————————

From Best Actress: The History of Oscar-Winning Women by Stephen Tapert. Reprinted with permission from Rutgers University Press. All rights reserved.

Roxane Gay

Roxane Gay's writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Best American Mystery Stories 2014, Best American Short Stories 2012, Best Sex Writing 2012, A Public Space, McSweeney’s, Tin House, Oxford American, American Short Fiction, West Branch, Virginia Quarterly Review, NOON, The New York Times Book Review, Bookforum, Time, The Los Angeles Times, The Nation, The Rumpus, Salon, and many others. She is the author of the novel An Untamed State, which was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize for Fiction; the essay collection Bad Feminist; Ayiti, a multi-genre collection; the memoir Hunger; and a comic book in Marvel’s Black Panther series.