On the last day of March in the year 1848, in the last hour, just before the clock on the first floor chimed midnight, Margaret Fox stifled a fearful cry by biting the end of her pillow.

“Katie, Katie!” she breathed quickly. “Wake up! Something’s happening . . .”

“I wasn’t sleeping,” responded her bedfellow.

“Then you heard it?”

“Of course, and I don’t think it’s done yet . . .”

No sooner had she spoken than a dry crackling, like bones breaking, resounded from the side of the staircase. Margaret counted seven knocks; the muffled chime of the clock seemed to be giving a musical response.

“Midnight!” she stammered. “Oh, I’m dying of fright! There’s someone there, it’s certain! A runaway slave maybe, or an Indian from the reservation who’s going to take revenge on us with a knife used for skinning buffalo . . .”

While Katie remained silent, her big eyes open like a sleepwalker’s shining in the moonlight, Maggie felt an icy blade of terror slide down between her shoulders and, tempted to call for help, was unable to issue any sound but the kind of squeak coming from a chicken being slaughtered. A small hot hand covered her lips.

“Shh,” Kate whispered, “our parents are sleeping . . .” Her little otter’s nose had such an air of rebellious exultation that their fear immediately turned to bewilderment and a wild, nervous laugh escaped from her. “Hey, listen, now Father is snoring . . .”

“Unless that’s Mother!” Maggie corrected, laughing even louder. “But what about the knocking at this hour?”

“It’s not the first time.”

“What, don’t you ever sleep?”

“It seems to me like it’s getting louder each night. Maybe someone’s trying to get through to us . . .”

“Are you crazy? There’s no one here except our parents and you and me! At least . . .” Fear crept between her skin and the cotton sheet all over again. Frozen, mouth dry, breath held, hands clasped around her throat, Margaret shuddered with the feeling that all of her senses were pointing her toward who knows what kind of abyss—her sight, her sense of smell, her hearing, every inch of her skin—perceived the moment with excess intensity. Powerless, however, she felt like a block of plaster inside of which a frantic bird was desperately flapping its wings.

The noises stopped both inside and out. The wind lay quietly down at the feet of tall trees. Even father had stopped snoring. The silence became so total that the thought of nothingness quickly reached a kind of perfection.

“Something’s there!” Maggie quavered from the bottom of her terror, her voice collapsed into the register of a very old woman. Through the open shutters, a ray of moonlight slid over a drawn silhouette perfectly motionless just in front of her bed. Her eyes bulging at this apparition, the adolescent let out a howl empty of any substance, convinced that she herself must be dead or unconscious.

“Come on!” said the shadow. “Follow me to the staircase . . .” Recognizing the muffled voice of her little sister, Maggie let out a mouse’s squeak. Immediately the catalepsy that had nailed her in place fell away like a lead suit of armor. She threw back the sheets and, unperturbed by that rush of air, walked fearlessly behind Katie.

“It most often comes from right there,” she said, pointing to an interior wall. “Other times it rises up from the basement.”

“I can’t hear anything now,” the adolescent noted with a survivor’s relief. Kate raised her little mammalian face up to her on which two pupils blacker than night surfaced.

“That’s because he’s waiting,” she said.

“What? And first of all, who are you talking about?”

“I don’t know. Maybe he’s waiting for us to give him a sign.”

With a slow look up and down, Maggie examined the ceiling’s beams, the somber wood walls, the worn steps that sank into themselves in the dark, the dying glow of the woodstove, and the surrounding darkness.

“But who? Who are you talking about?” she repeated.

“The spirit!” Kate shot back.

“You mean a . . . a ghost?”

Her sleepy consciousness was filled with the image of a huge coffin, laid out with a huge glowworm inside it. Overtaken by a shapeless sense of panic, Maggie finally swooned and tumbled half-unconscious down to the foot of the stairs from the terror of being devoured by the glowworm. The fall resulted in a house filled with commotion. Their grumbling father, lamp in hand, and mother, distraught, came to the rescue of the fainted one whose younger sister imagined could be cured by hugs and tickles.

They led her, a big ragdoll with tangled legs, back up to her room. While their mother had already set about trying to revive her with salts and slaps, their father lit a tallow candle at her bedside table.

“What on earth were the two of you doing on the staircase at this hour?

Withdrawn, resolutely silent, Kate smiled at her own thoughts.

“It’s impossible to put oneself into such a state!” their mother added. “Smart young girls such as yourselves! What, were you going berry-picking for jam together under the full moon?”

Maggie’s eyelids fluttered a few seconds on a shadow silhouetted in the doorframe. Under the candle’s dancing flame, Kate’s angelic smile took on a bit of a demonic air, while her lips, animated by the golden reflections, seemed to hold back silent, mocking, curses addressed to the company.

“Well, ask her!” Maggie blurted, pointing with an accusatory finger. “Katie was leading me. She claims there’s a ghost in the house . . .”

Their mother, disconcerted, threw worried looks at her spouse and at the dark corners of the room. She was a thick and well-groomed woman, eternally dressed in an embroidered bonnet, her black hair gathered at the nape of her neck, with plump and, despite farm labors, very white hands, a copious bosom beneath her blouse, and a strong nose in the center of a rather pleasant face that, with makeup, would have appealed to a horse breeder or a Rochester merchant. Her keen eye landed finally on the younger girl.

“What is this story frightening everyone, hmm, Katie?”

“It’s not a story. You must have heard the knocks in the walls and furniture downstairs . . .”

“Goddammit!” their father exclaimed. “So you’d like to make us look haunted to our neighbors? They already mistrust newcomers. I don’t want to hear any more of this madness starting from this day on!”

“Don’t curse at your daughter,” their mother begged, “or it will be you the reverend should punish . . .”

“But,” dared Margaret’s flowing voice, “it’s true that there are noises. And what if the house is trying to harm us? I wish so much that we could just go back to Rapstown!”

“There are no noises!” the man cut her off. “Or let the devil take me to burn! It’s an animal, it’s the wind, it’s creaking wood . . . Now I’m going to turn my eye toward a last bit of sleep . . .”

As her father left, Kate moved quickly toward the window to avoid one of those affectionate slaps marking the end of a minor conflict. It’s just that he had the paws of a bear that could tear your head off! She didn’t despise him, the poor old man. He was just of country stock. So devoid of mind that he could only believe the pastor’s sermons. A descendant of patriots expelled from Canada during the War of Independence, he belonged to the dreary species of farmers, all stubborn bigots and halfway between the slaves, black or white, and the arrogant aristocracy of animal breeders.

As soon as her father left, Kate started to laugh. “It’s not an animal, it’s not the wind, it’s not creaking wood! It’s a cloven foot, I’d swear it on the horns of our only cow!”

Their mother feebly bustled about, frightened, her enormous chest undulating under her nightgown.

“Don’t be crazy! The devil only comes if called. Go back to bed and not another word! You need to sleep now, for the good sleep of little girls chases away all these wicked inventions . . .”

Kate slipped under the covers, already half-anesthetized by their mother’s quavering chant. Recovered from her fall, Margaret sighed at her side. Her long lashes fluttered up, silhouetted by the candle next to the bed, giving the impression that they caught fire with each blink of her eye. Then, from below, three raps were distinctly heard.

“Momma!” Kate murmured. “See, I told you someone was there . . .”

“Shh, shh, it’s possible, but sleep, sleep without any fear, your good mother will keep him in line with her fire iron . . .”

“Don’t hurt him too badly, please! Don’t give Mister Splitfoot too hard a time.”

“Mister Splitfoot? Good Lord, now who is that? Well, forget all of this for tonight, I’m blowing out the candle and the moon, as we used to say.”

Mrs. Fox, standing in the reconstituted dark, and despite being taken aback herself by the phenomena that appeared to be assailing her daughters, thought then of the faraway past, when she was their age, when she believed in the marvelous phantoms of love and of the future. Softly, right there, at the bedside of her little girls, the farmer’s wife began to sing a very old ballad that rose up to her lips from some memory she didn’t know . . .

Well a hundred years from now

I won’t be crying

A hundred years from now

I won’t be blue

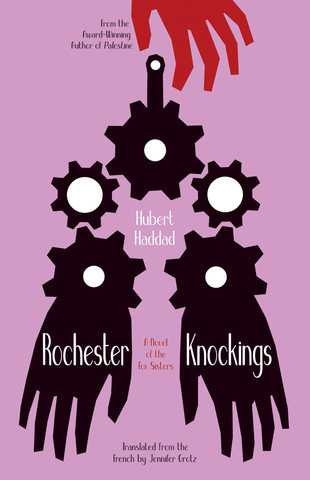

From ROCHESTER KNOCKINGS: A NOVEL OF THE FOX SISTERS. Used with permission of Open Letter Press. Copyright 2015 by Hubert Haddad. Translation Copyright 2015 by Jennifer Grotz.