For much of human’s time on the planet, before the great delusion, we lived in cultures that understood us not as “masters of the universe” but as what my Haudenosaunee neighbors call “the younger brothers of creation.”

Long before Aristotle placed our species atop the anthropocentric Scale of Nature, long before Western religions declared that only humans were made in the image of God, the peoples of Turtle Island were guided by the kincentric worldview of “all my relations.” It is a philosophy and set of practices based on knowing that the same life force animates us all and binds us as relatives—tree people, bird people, and human people. This kincentric way of being grew from the understanding that we are linked in webs of reciprocity, where the survival of one depends upon the survival of the other. Simultaneously scientific and spiritual, this way of thinking has evolutionary adaptive value in guiding ecological relationships toward mutual flourishing.

But a few centuries ago—an eyeblink of time in the lifetime of our species—humans forgot this truth and began an unwitting social experiment in worldview. The Western world seems to have asked the question “What would happen if we believed in a pyramid of human exceptionalism, the notion that our species stands alone at the top of the biological hierarchy, fundamentally different and superior to all others? What if a single species, out of the millions who inhabit the planet, was somehow more deserving of the richness of the Earth than any other?

And not only that. In this experiment, all the ecological laws that constrain growth and consumption do not apply to us. What would happen if we assumed that the laws of thermodynamics had been repealed on our behalf and endless growth was possible? Furthermore, the experiment tests this hypothesis: What would happen if we behaved as if the Earth were nothing more than “stuff”—a strictly materialist, utilitarian view of the Earth—and, moreover, all the stuff belonged to us?

If we are to heal the illness, we must first understand the source.The results of that experiment are in. We find ourselves teetering on the brink of climate catastrophe, on the cusp of the Age of the Sixth Extinction.

It seems that we suffer from a grave cultural illness that we seem unable—or unwilling—to cure. We know what we need to do but fail to do it, putting a warped notion of economic well-being ahead of the continuity of life. The medicine lies within our reach, untouched. If we are to heal the illness, we must first understand the source.

It is this deep-seated fiction of human exceptionalism that fuels the rampage of exploitation, commodification, and hyperconsumption, and that has us facing a crisis of survival of life as we know it.

Perhaps it grew from the religions that chased divinity from the Earth into the sky, where it was said we would follow. In that upward gaze, those humans lost sight of our earthly gifts and our mutual responsibilities. They abandoned the notion of “all my relations” for a hierarchy of being in which humans are perched squarely atop the pinnacle of creation, just below the angels, with all our sustainers, the plant and animal people beneath us, not as family but as property. Human exceptionalism cuts us off from ecological compassion and sets the living world outside our circle of moral responsibility.

Despite our ecological and genetic intertwining with other species, we are plagued with an epidemic of loneliness. We suffer a deep estrangement from the other beings on the planet, a phenomenon that has been called “species loneliness.” Species loneliness is a symptom of the disease of human exceptionalism. Thinking that we are alone, we cannot turn to other species for comfort, nor benefit from their counsel and compassion. In some deep-seated place, we also carry a shadow of shame for how we treat our relatives. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world where we stood tall in receiving the respect and gratitude of other species.

The choice of human exceptionalism is an active one, with costs and benefits. Accepting kinship comes at a cost of reciprocal obligation; being family means you take care of one another. Choosing the myth of human primacy gives us permission to designate our kinfolk as natural resources. Acknowledging kinship with other beings would mean that we would lose the easy, unearned privilege that enables exploitation. It is a moral choice veiled as an economic argument. But it is not a winning evolutionary argument.

We crave belonging, but in our human exceptionalism we are left, instead, with only longing. When we deny kinship with other species, we become blind to the world as a gift. When we choose human exceptionalism, we turn our backs on the reciprocal joys of loving kinship. Instead, we endure the burden of estrangement from the ones who give us everything we need. The price of this estrangement seeps its way into our behaviors—overconsumption, self-absorption, obsession with power and violence—filling the space where relationship might be.

We do not sustain ourselves; it is the natural world that gives us water, without which we would not be.Cultural evolution has come to shape the lineage of humans nearly as strongly as biological evolution. Will the cultural construct of human exceptionalism lead to the continuity of our lineage or to an evolutionary dead end for the species that chooses a path of mutual destruction? If we are to persist here on this beautiful Earth, the next step in our cultural evolution is to shift our thinking from rights to land, to responsibility for land.

As Anishinaabe people, embedded in the “all my relations” worldview, we are guided by the Seven Grandfather Teachings, the cultural values that are understood to support a good life in balance with all our relations. Among them is edbesendowin, which translates in English to something like “humility.” According to language teacher James Vukelich, the word actually means “to think lowly of oneself,” not in the form of false modesty or low self-esteem, but, rather, not to consider ourselves to be above our relatives.

It contains the realization that our lives are totally dependent on the gifts of others. It is remembering that we do not sustain ourselves; it is the natural world that gives us water, without which we would not be.

It is the plants and animals who give us food, without which we would not be. Warmth and medicine and learning are gifts; even the air we breathe is given to us by the breath of others. These gifts are understood as the unconditional love of relatives for one another, before which we can only bow in gratitude. Humility expresses itself in gratitude and blossoms into reciprocity, into caring for the lives that care for us.

This is what kinship feels like to me, beyond genetic relatedness to a sense of being held by the world, of belonging. Kinship implies a kind of obligation; we are all responsible for sheltering that spark of animating spirit that gleams in every single being, in all our relations.

Kinship is the medicine for human exceptionalism; we need only to choose that healing draft.

I sometimes despair of my inability to change the fearsome trajectory of our species, but there is one place where I have total power—and that is in how I think. I choose to jump off the jagged pyramid of human exceptionalism and land in the soft embrace of all my relations. I choose kinship. You could, too.

__________________________________

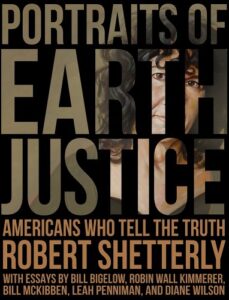

Excerpted from Portraits of Earth Justice: Americans Who Tell the Truth by Robert Shetterly. Copyright © 2022. Available from New Village Press, an imprint of NYU Press.