He had spent several months, exactly from the beginning of April 2014 until the end of March 2015, working on his diaries, taking advantage of an illness, a passing one according to the doctors, which prevented him from going outside; as Renzi would say, joking with his friends, going outside was never a temptation for me, but I never had any interest in what we might call going inside either, or being inside, because inevitably, Renzi told his friends, one wonders, inside of what?, and so it turned out that, thanks to—or as an effect of—that passing illness, he could finally dedicate all of his time and energy to reviewing, rereading, revisiting his diaries, which he’d spoken of too much in another time, for he’d always been tempted—in another time—to talk about his life, although it wasn’t quite that, but talking about his notebooks.

Yet he’d never done it, and scarcely alluded to that personal, private, “confidential” work, although what he’d written in his notebooks had, so to speak, often passed unchanged into his novels and essays, into the short stories and narratives that he’d written over the course of the years.

But now, taking advantage of the illness that had suddenly befallen him, he could shut himself away in his study and dedicate himself to transcribing the hundreds and hundreds of pages written in his cursive scrawl inside notebooks with rubber covers. And so, when he found himself afflicted by a mysterious illness, which had visible signs—for example, he had difficulty moving his left hand—even though its diagnosis was uncertain, then, Renzi said, he began an interior work, something done inside, in other words, without venturing into the street.

He hadn’t read his diaries chronologically; I couldn’t bear it, Renzi told his friends. Before, on several occasions, he had undertaken the task of reading them and trying to type them up, to make a “clean copy,” but within a few days he would have deserted that horrible chronological succession and abandoned the project.

Even so, Renzi intended to publish his private notes according to the order of the days because, after rejecting other forms of organization such as, for example, following one theme or person or place over the course of the years in his notebooks and giving his life an aleatory and serial order, he’d realized that the confusing, formless, and contingent experience of living was lost in the process, and so it was better to follow the successive arrangement of days and months.

He had suddenly recognized that his work—but was it work?—of reading, investigating, tracing through his notebooks was one thing, and the published order of the notes that recorded his life was a very different matter. The conclusion: reading isn’t the same as giving to be read. As he’d learned in college, the research is one thing and the exposition another; for a historian, the time spent searching blindly in the archives for things you imagine are there is antagonistic to the time required to present the results of the investigation. The same issue arises if you become a historian of yourself.

And so, he’d made up his mind to present his diaries in chronological order, dividing what was written into three large parts that observed the phases of his life, because, in reading the notebooks, he’d discovered that a fairly clear division into three eras or periods was possible. But, in April of the previous year, when faced with the task of rereading and copying the entries of his diaries, he realized it was unbearable to imagine his life as a continuous line and quickly decided to read through his notebooks at random.

Life must not be viewed as an organic continuum, but rather as a collage of contradictory emotions that do not at all obey the logic of cause and effect.They were filed haphazardly in cardboard boxes of varying provenance and size; they’d been with him everywhere he went, those notebooks, and the disorder that came with each move had thus broken any illusion of continuity. He’d never attempted to file them in an orderly way. He would change their placement and position according to his mood, would stare at them without opening them, for example, strewn across the floor or piled on his desk, and be overwhelmed by the amount of physical space that his personal notes occupied.

One afternoon, following his grandfather Emilio’s example, he’d decided to set aside a room exclusively for his diaries. The fact that they would all be in a single place and, above all, that the door to them might be closed, even locked, reassured him. Yet he never did it. If he had wasted part of his life writing down events and thoughts in a notebook, he wasn’t going to waste a room of his house on top of that, only to sit and spend entire nights reading and rereading the catastrophic stupidity of the way he lived, because it wasn’t his life, it was the passage of days.

And so he asked his friend, the shopkeeper on Calle Ayacucho, for some cardboard boxes, and he used these boxes that once held all manner of products to store them away, packing them in no order, and finally, so as not to be tempted, he decided he would turn his back to the notebooks, contained inside eight boxes, and then, not looking but feeling his way, he would take one out. In that way, Renzi told his friends, he had managed to completely dismantle his experience and move from his notes about months of loneliness and inactivity to another notebook in which he found himself active, lucid, conquering.

In that way, he began to perceive that he was several people at the same time. At certain points he would encounter a failure, a good-for-nothing, but then, reading a notebook written five years later, he would discover a talented, inspired, and triumphant young man. Life must not be viewed as an organic continuum, but rather as a collage of contradictory emotions that do not at all obey the logic of cause and effect, not at all, Renzi repeated, there’s no progression and of course there’s no progress, no one ever learns from their experience, unless they’ve taken the rather deranged and unjustified precaution of writing and describing the succession of days, for then, in the future—and only in the future—the meaning will blaze like a fire on the plain, or rather, will burn within those pages.

Unity is always retrospective, all is intensity and confusion in the present, but if we look at the present once it has already passed and situate ourselves in the future, in order to once again see the things we’ve lived through, then, according to Renzi, it could become somehow clearer.

He had spent those many months, from the beginning of April to the end of March, immersed in the abyss of his existence, sometimes murky, sometimes clear and transparent. Several times he’d become captivated by one writer or philosopher for a while and would spend months immersed in the mass of writings left by that single author—Malcolm Lowry or Jean-Paul Sartre, for example—and read everything they’d written and everything that had been written about them, but now, although the system, to think of it that way, was the same, everything was different because the subject of the investigation was himself, the self, he said, with a burst of laughter.

The self, one’s essence, and yet, since one isn’t just one but rather another and then another still, in an open circle, it is understood that the form of expression must be faithful to contingency and disorder, and its only form of organization must be the flow of life itself.

Since April of the previous year he’d dedicated himself to that project, along with the invaluable and sarcastic help of his Mexican assistant, Luisa, and Renzi had dictated to her, just as he was dictating now, all of his notebooks, and they’d managed, amid jokes and laughter, to swim through that abyss of waters at once murky and transparent. That day, Monday, February 2nd, they had reached the shore and could look back at what they had done from a different perspective.

Amid the mire of pages written, read, dictated, and amended, certain events, certain incidents or situations had shone out, things he’d captured or glimpsed while dictating to her, as though he were living through them once more. All experience is, so to speak, retrospective, an après-coup, a later revelation, save for two or three moments of life in which passion defines temporality and fixes its enduring sign upon the present.

The idea of surgery as a medical metaphor for state oppression is very common in my country’s history.Passion, Renzi repeated, is always present; it is actuality, manifested in a pure present that lingers on through life like a diamond. If you return to it, you are not remembering but living through it now, once more, in the present, ever vivid and incandescent.

For example, back in that time, a meeting with a woman, alone and undefeated yet also aching and broken, at a modest apartment in Villa Urquiza, furnished in an anonymous style, its kitchen like so many kitchens in Buenos Aires, expansive, with a white wooden table where you could sit—as she and I did that day—and drink yerba mate.

I saw only the kitchen and living room—the dinette, as it’s called—with framed photographs and decorations that were almost invisible for being such ordinary sights, and I never saw the bathroom but can imagine it—the mirrored medicine cabinet, the white tiles—just as I can imagine the bedroom with the double bed, used for many years by only one spouse—the one who had survived.

An apartment like any other, on the sixth floor, with a TV on a table to the left side of the living room, facing white armchairs. The truth shone out in such a common place. And that’s why I remember that meeting so clearly; I need only shut my eyes to be right back there. There’s barely more than a terse reference in my notebooks, the date and time and a note in passing so as not to say too much during a time when any word or gesture could bring harm to the person you mentioned and thus exposed. It was a precaution that did not guarantee anything or allow you to imagine you were safe but served only as a record that you’d lived in those dark days.

At the time, I wrote: Today I visited the Oracle at Delphi. I don’t call her that because she—the wounded woman—presents herself that way, but because of the composed clarity of her speech. An oracle with no enigma; the confusion, at any rate, is on the part of the one who comes seeking advice. I can remember it better and more vividly than if I’d written it all down, and, for me, that piece of evidence—every time I’ve come face to face with it or recalled it—has served as proof of a single moment in which life and meaning were joined together. But what was the cost?

That’s why I’ve spoken of those as “the plague years.” In Greek tragedy, it was a way to refer to social evil. A plague that devastated a community as a result of a crime perpetrated in the very site of state power. A state crime that—in the form of an epidemic—caused terror and death among the citizens. A metaphor, in short. Quite opposite to the metaphor, a familiar one in our time, of the despotic power associated with a surgeon who must operate without anesthesia and cut open the ailing body of the nation.

The idea of surgery as a medical metaphor for state oppression is very common in my country’s history. A doctor sees his obligation, as those bastards say, to act upon the body in order to cure the political disease that, so they claim, is afflicting the nation.

By contrast, in the Greek tradition, the calamity is seen as a result of the crime being perpetrated in the state; who murdered Laius, the king, at a cleft in the road? The plague, then, is the result of a crime that befalls the populace, and the plague years are the dark years during which the defenseless suffer under a social evil, or rather, a state evil, descending from the seat of power onto the innocent citizens.

And so, in order to remedy the wrong or to find some relief or escape, I had to visit the Pythia, that woman, a cross between seer and bird, to face her and to hear her song. That lady, whom I met in secret, was compelled to be beyond reproach in her life and habits. And so she was, Antonia Cristina, whose powers I only glimpsed years after visiting her in her modest home, at Delphi, that is, in Villa Urquiza.

That too was the meaning behind the title of Camus’s novel, The Plague, the first book I read “myself,” which is to say, I used it so that I could tell a woman, a girl really, my version of what I’d read, and I don’t remember what I told her but I do remember that night I spent reading the novel, furiously, as though the book were alive, inside me, even as I was reading it for her. And that’s all I’ve done ever since, reading a book, or rather, giving a book to someone who’s asked to read it.

Those empty caskets invoked the unburied bodies that had ravaged, and for years to come would ravage, the memory of the country.For Camus it is Nazism, the German occupation, which causes the epidemic that sweeps across Algeria. The other meaning of the plague is that it gives rise to a series of narratives for which it is the condition, not the subject, as is visible in Boccaccio’s Decameron; always, amid the terror of death, there is a group of people who shut themselves off in order to tell, by turns, some stories. The danger, the terror, the curse of a reality with no escape is often transformed into tales, little stories that circulate in the middle of the night, relating imaginary versions of the lived experience of those dark days and making it possible to bear through them and survive.

The telling of stories brings relief from the nightmare of History. For example, in the past I’ve related the anonymous story that began to circulate around Buenos Aires in those days. Someone said there was someone who had a friend who, one morning, at a railway station, in a suburb of the city, had seen a freight train passing, slow and silent, heading south with a load of empty coffins. That was the story that circulated by word of mouth in the midst of the military plague and the horror of Argentina. A perfect story that both said and did not say, that alluded, in its image, to the reality we were living in.

For those empty caskets invoked the unburied bodies that had ravaged, and for years to come would ravage, the memory of the country. They were heading south, a brilliant detail that referred to the desert, but also, of course, to the Falklands War, which the murderers had been preparing for months as an escape route and which the story seemed to anticipate. How did they know the coffins were empty? It was, Renzi thought, the gravitational pull of fantastical literature, which had been, in our culture, a very original way of writing that allowed us to postulate unsettling realities that contain more truth than reality such as it is experienced.

The other highly political detail in that story was the presence of a witness. There was always someone present who saw what happened and could recount it; there’s always a witness at the scene of the event, an individual who sees and then goes on to spread the story. In this way, there is a certain poetic justice in the world that makes it possible for social crimes to be revealed and made known.

There is a witness who gives testimony and shares the things they have lived through and the things they have seen. Showing them and making them visible, for their account, said Renzi, does not judge, it only implies and, in that way, allows the things that History conceals to become known.

__________________________________

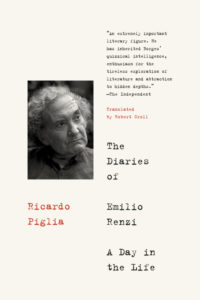

From The Diaries of Emilio Renzi: A Day in the Life by Ricardo Piglia. Used with the permission of the publisher, Restless Books. Translation copyright © 2020 by Robert Croll.