Revisiting the Fieldnotes from Our Time with the Saamaka

Looking Back at an Ethnographic Experience, 50 Years Later

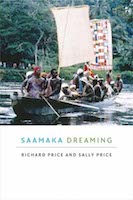

“What do they do all day?” a visitor to Dangogo once asked Nai within our earshot. “They just keep looking at paper,” she replied. Indeed, we often heard this explanation about why we tended to spend part of each day quietly inside our house, not something that Saamakas did. At the end of our stay in 1968, all that paper was put in trunks, carried downriver in a canoe, and shipped off to New Haven where Rich began drawing on it for a dissertation while Sally turned her attention to our upcoming life as parents.

It wasn’t until 50 years after our first encounter with Saamakas and the publication of more than two dozen books about them that we decided to revisit the nitty-gritty of that ethnographic experience. The field data that we had carried with us from one home to another over the years, and which now sat in a row of four file cabinets in our house in Martinique, consisted not only of desiccated paper, frazzled at the edges, but also shoeboxes filled with tape cassettes, bulging notebooks with transparent sleeves containing black and white negatives and contact sheets, plastic boxes holding color slides, manila envelopes with prints of various sizes, and more—including additional material from our returns to Saamaka in the 1970s.

A fieldnote page—rsp 536.

A fieldnote page—rsp 536.

We began by emptying three deep file drawers labeled “Sarfieldnotes 1960s” and set the contents on a table in our study. Thousands of single-spaced typed pages, each headed “rsp” or “shp” on the upper right and bearing scribbled tags in the left margin (“Apuku,” “co-wives,” “crop calendar,” “cicatrization,” “drum language,” “address terms” . . .), were written in an indiscriminate thicket of English, Saamakatongo, and abbreviations thereof. We took a few days to scan them into PDFs in the hope that particular words would be roughly searchable in spite of all the typos and the graphic idiosyncrasies of our compact Hermes typewriter.

A 5 × 8–inch accordion file with pockets labeled A through Z fell apart when we picked it up. The contents, quickly transferred to a shoebox, consisted of a set of standardized data on every individual in Dangogo. We had used a template card with carefully excised rectangles designed to receive the data—age, parents, parents’ clans and residence, detailed conjugal history, children born, children raised, coastal trips, residence history, garden camps, possession gods, formal friendships and, when known, the person who had supervised their rite de passage to adulthood. Conjugal history (sometimes requiring several cards) was entered through the holes of a second template card. And an additional set of cards contained less complete data on other people—mostly deceased relatives of the Dangogo residents, but also some of their spouses.

A mottled notebook labeled “Log Book 1967,” eaten by insects on the cover but relatively intact inside, recorded six categories that we had filled in faithfully each day—food, weather, individual comings and goings (who made day trips to other villages, upriver camps, or the mission clinic; who was in the menstrual hut; etc.), ritual activities (oracle sessions, libations, various kinds of divination, etc.), special events (ancestral feasts, council meetings . . .), and our own activities. Halfway through the year, we added the use of a template to keep track of how many people slept in Dangogo each night, distinguishing adult versus child, male versus female, and resident versus visitor. There were also two bulging manila envelopes containing densely filled 5 × 8–inch cards on which we had recorded the whereabouts of more than one hundred people each day between September 1967 and November 1968—whether they slept in Dangogo, were working in upriver garden camps, made trips to the mission clinic or other villages, and more.

The information on kinship relations that appeared on nearly every page of our fieldnotes had eventually been consolidated into multi-page genealogies, scotch-taped together left and right to create scrolls that allowed the connections over eight generations to be included.

And there was a notebook devoted to our coverage of material culture: a list of the 12 models of machetes, specifying what men owned each kind, entries for every kind of clothing, from gravediggers’ kerchiefs and button earrings to embroidery stitches and different styles of patchwork capes, pages on every kind of ritual paraphernalia we’d heard of, and so on. For each object we had annotated the information we’d collected, the photos or sketches we’d made, and the details that were still needed.

All this was part of a larger attempt to document Saamaka material culture—compensation for the fact that we had declined a 1967 request from Bill Sturtevant to make a collection for the Smithsonian, where he was a senior curator. It had been a tempting idea, but we decided that taking on the role of collectors could compromise the non-commercial relationship that we were taking pains to establish with our neighbors. So we said no. But then Bill proposed as an alternative that we make a virtual collection—an exhaustive inventory of the material life of Saamakas—including physical properties, historical antecedents, developments over time, production techniques, linguistic terms, hierarchies of value, conceptual associations, gender dimensions, ownership patterns, regional differences, and more, stopping just short of acquiring the physical objects. So that is what we did.

A fieldnote page—shp 579. The weave of a basketry press used to make awara palm oil compared to that for a cassava press.

A fieldnote page—shp 579. The weave of a basketry press used to make awara palm oil compared to that for a cassava press.

And of course there was more to be had in the file cabinets—maps, loose memos, letters from the field, and other miscellanea. We also found a file box with almost two thousand 3 × 5–inch slips, arranged in 170 cate- gories (“Snakegods,” “Menstrual Seclusion,” “Kinship Terms,” “Hunt- ing and Fishing,” . . .), indexing the relevant pages of our fieldnotes and noting the specific information each one contained. Compiling it had been exceedingly time consuming, but in a pre-computer age, that’s the sort of donkeywork that you had to do to keep track of such diverse information.

It may be worth underlining the difficulties (better, impossibility) of recapturing or recapitulating the learning experience that fieldwork in another culture involves. Reading through our fieldnotes, we were struck by how much of the significance of particular comments depended on background knowledge of the things being referred to that was not explicitly spelled out, knowledge that readers who hadn’t participated in our experiences wouldn’t get. As we wrote up our day’s activities, we were constantly building on assumptions about what we’d already seen, heard, and learned. Making sense of a note that “Seema worked on Djeni’s house,” for example, depended on knowing the relationship between Seema and Dosili, and understanding that because Djeni was pregnant, her husband Dosili had a taboo on doing this work.

When we already knew these sorts of things, we didn’t need to write them into our fieldnotes, and this was true even at the very beginning of our time in Saamaka. We were writing mnemonics for ourselves, not for outsiders. In this book, we stick much more closely to our fieldnotes than in any previous work, but as in Zeno’s paradox, one can never quite catch the turtle. What we attempt here is to get as close as possible to those experiences of wonder, frustration, and learning, remaining as faithful as we can to the fieldnotes while still retaining coherence for those who haven’t had the good fortune to experience Saamaka life in person.

__________________________________

From Saamaka Dreaming by Richard Price and Sally Price, courtesy of Duke University Press. Copyright Richard Price and Sally Price, 2017.

Richard Price and Sally Price

Richard Price has written numerous prize-winning books, including Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination and Rainforest Warriors: Human Rights on Trial. Sally Price has written studies of the place of “primitive art” in the imaginary of Western viewers, including Primitive Art in Civilized Places and Paris Primitive: Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quai Branly. Their coauthored books include Romare Bearden: The Caribbean Dimension.